Women

have been at the forefront of struggle in Honduras throughout its

history, from fighting dictatorships to challenging political

corruption to seeking civil improvements such as gender parity in

politics and education. The recent presidential election of Xiomara

Castro Sarmiento Zelaya

of the Libertad and Refundación (Libre) party has exhilarated

women from various sectors and in the diaspora. In a country battered

by 12 years of impunity, corruption, and aggressive neoliberalism in

the wake of the 2009 U.S.-backed coup, Castro’s victory—and

her pledge to convene a National Constituent Assembly to rewrite the

constitution—is at once a vindication and ray of hope for

women’s rights and other hard-fought social struggles.

Speaking

with the women in my family about this momentous win, a flurry of

stories emerged. My grandmother, for instance, was a Liberal Party

activist who opposed the Nationalist Party and served as a poll

worker in 1954, a volunteer job that could have resulted in jail time

or even death. During this time, treatment of Liberal Party members

was akin to the persecution and harassment of members of Communist

parties.

For

a century, until the 2009

coup,

Honduras was ruled alternately by two oligarchic political parties,

the Nationalist Party and the Liberal Party. During the 1954

presidential elections, Liberal candidate Ramón Villeda

Morales, affectionately called Pajarito

Pechito Rojo

(little red-chested bird), was seen by supporters as the hope to end

the terrible reign of Tiburcio Carías Andino’s

Nationalist Party. Although the Communist Party had been founded the

same year, the real battle for the presidency was between the

Nationalists and Liberals.

Carías

Andino, a fierce ally of U.S. banana companies, had ruled as a

dictator for 16 years. He used military might to terrorize Liberal

Party leaders, crack down on activism or organizing, and threaten

workers and campesinos into voting for his party. In 1946, Liberal

Party members were gunned down at a rally in San Pedro Sula, sparking

much needed organizing and resistance against the regime. In the 1954

election, visibly rigged by the Nationalist Party apparatus,

activists had to circumvent the military, intimidation, and

corruption to vote. Pajarito won in an upset

Voting

was not easy under Nationalist Party rule, and women had an important

role. Less likely to be detained by the military than men, women like

my grandmother—with my mother in tow—were tasked with

retrieving blank ballots from departmental capitals and distributing

them to all the major towns (pueblos),

such as my mother’s hometown of San Nicolás de Copán.

The women, who did not yet have the right to vote, traveled by trucks

that resembled buses and then hiked to San Nicolás up a muddy

mountain inaccessible by car. On the way, they had to evade

soldiers—known to destroy blank ballots and intimidate or

coerce activists and voters—as well as the local priests who

sided with the military. En route to the elementary school that

served as San Nicolás’s polling station, located across

the town plaza from a Catholic Church, my grandmother and her

compañeras

looped through people’s yards to avoid the military patrols on

horseback. These were dangerous and unjust times when the military,

empowered by the Nationalist Party, unlawfully raided homes and

jailed, disappeared, and killed people.

Once

the ballots were safe, my grandmother, cousins, and the other young

women positioned themselves at strategic points in the town to wait

for villagers from nearby hamlets and help them get to the precinct

to vote without facing military coercion. After voting, villagers

were offered food in my grandfather’s house and other nearby

opposition homes. This irritated the military, and during the 1954

election, soldiers barged into the house and searched it. Later, in

the cover of night, my grandparents, their daughters, and children

fled the house to hide from the military as the results were

declared

Literate

women—a small portion of the population—won suffrage by

congressional decree on January 25, 1954, though they did not

officially vote in their first election until 1957. For decades

after, women have shared stories with younger generations of what

life was like under dictatorship, authoritarian regimes, and military

rule, when their rights were nonexistent.

The

sometimes-violent trading of power between Liberals and Nationalists

was the predictable convention until 2009, when Liberal Party

members, in collusion with elites and the U.S. State Department,

executed a coup against their own party. The putsch removed President

Manuel “Mel” Zelaya

in very similar fashion to the ousting of Villeda Morales in 1963

after a brief period of democratic rule.

The

resistance to the 2009 coup was led by women, who filled the ranks of

most social movements. Women have stood on the frontlines to defend

ancestral lands and rivers, their rights as educators and healthcare

workers, the right to live free of violence, and the right to make

choices about their bodies and identities. Women have also been

critical in shining light on the role of U.S. intervention in the

region and the Cold War-era politics of the internal enemy that

sought to disappear and torture students and activists perceived to

be communists. These are the memories grandmothers have shared with

granddaughters and are now being passed on to millennial

activists opposing

the regime of outgoing President

Juan Orlando Hernández (JOH).

Similar

to the determination to make the people’s voices heard at the

ballot box in 1954, it is no surprise that Hondurans—especially

young people and those most disenfranchised in the 12 years since the

coup—voted in unprecedented numbers in the 2021 election. This

could be a new Honduras. And as the first woman president, Castro is

one part of a larger legacy of women actors and their daughters who

made her victory possible.

An

Unprecedented Pro-Women, Pro-LGBTI Agenda

In

her campaign and platform,

Castro embraced gender rights and sought to address femicides and

structural violence against women and LGBTI communities—issues

ignored in previous campaigns. She promises to change the new penal

code, approved a few months ago by the Nationalists in Congress, to

rectify reduced sentences for crimes against women. She also proposes

to counter hate speech and the conservative crusade against so-called

“gender ideology,” advocates for sex education in schools

as tool to prevent teen pregnancy, and calls for gender parity in

politics, where women are underrepresented.

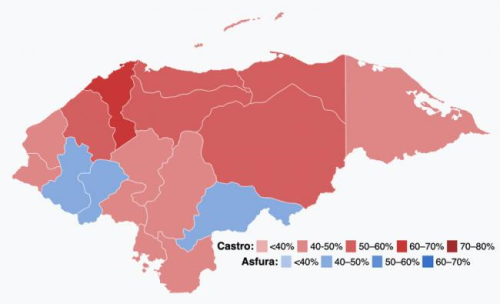

Results

in the 2021 presidential election, by department. Xiomara Castro won

with 51.1 percent over Nasry Asfura of the National Party's 36.9

percent. (CalciferJiji / CC BY-SA 4.0)

On

immigration, Castro calls for a “humanist migration policy”

to address forced migration and for a reduction of fees on

remittances. In this process, she promises to work both with the U.S.

government and the Departamento 19, or immigrants living outside of

Honduras. At the same time, she promises to guarantee the rights of

Hondurans—including immigrants, regardless of their status—to

pensions, social credits, and other benefits that will make it easier

for them to return if they choose.

But

the most far-reaching policy for women is Castro’s support of

the right to sexual and reproductive rights, including the right to

choose and access reproductive technologies and contraception methods

that respect women’s choice.

Castro’s

call for family planning and access to contraception, particularly

the “morning after pill” and contraceptive pill, as well

as her pledge to decriminalize abortion in cases of rape, threats to

the pregnant person’s life, and fetal abnormalities, and her

support for sex education represent a large leap from the positions

of any previous government. Further proposals promise the recognition

of women’s work, support for domestic violence shelters for

survivors, and the creation of centers for the reinsertion of

deported women into society.

Her

plan also features special attention to lesbian, gay, bisexual,

trans, and intersex communities, calling for protections against hate

crimes and violence, proper investigation of crimes, and introduction

of a gender identity law that would allow trans and gender

nonconforming people to change their names and genders on their

identity documents. These moves—unprecedented in Honduras—would

bring the country in line with the recommendations in a recent

Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruling

that found the Honduran state culpable in the 2009 murder of trans

activist Vicky Hernández.

Castro

has committed to recognizing ILO Convention 169, which Honduras

ratified but never implemented. This would guarantee Garifuna and

Indigenous communities’ rights to free, prior and informed

consent, allowing them to weigh in and even oppose land development

projects on their territories. It would also create opportunities to

advance bilingual education and healthcare and other critical

demands.

The

Garifuna community, in particular, was deeply affected by the reign

of the Nationalist Party, which allowed rich landowners to steal

communal and ancestral land. Garifuna and Indigenous women have led

important land reclamation efforts to counter the displacement that

has forced their communities into an exodus. Importantly, in the

National Constituent Assembly process, Castro vows

to propose

the creation of a Congress of Afrodecendant and Indigenous

Communities that would have the power to administer autonomous zones.

This would be a stark reversal of the controversial ZEDEs

law—passed under JOH’s leadership in Congress and

expected to be overturned by Castro and the new Congress—that

sought to auction off public land to foreigners to create enclaves

tantamount to private cities. It would also deliver on a key demand

of the post-coup resistance: redrafting of the constitution to

refound Honduras while including those most disenfranchised

historically. In other words, including those who built the social

movements that brought Castro to power.

Castro

may confront the wrath of the right wing, conservative elites,

organized religion, and other patriarchal forces in Congress and in

sectors aligned with U.S. interests. The key challenge is how to go

from vision to actual policies that will materialize in people’s

lives. Castro will need to involve the Afrodecendant, Indigenous,

feminist, and LGBTI social movements in this process as a first step

to ensure its success and ample popular support.

Castro

may confront the wrath of the right wing, conservative elites,

organized religion, and other patriarchal forces in Congress and in

sectors aligned with U.S. interests. The key challenge is how to go

from vision to actual policies that will materialize in people’s

lives. Castro will need to involve the Afrodecendant, Indigenous,

feminist, and LGBTI social movements in this process as a first step

to ensure its success and ample popular support.

Many

who protect the land, rivers, and ancestral territories are women.

When their families are targeted, the entire community is affected.

The JOH administration relentlessly persecuted these community

members. In fact, during the bicentenary celebration of Honduran

Independence from Spain, he declared water and land defenders,

feminists, and LGBTI communities “enemies

of Independence.”

Of

course, it was JOH and his Nationalist Party that proved to be the

enemies of the people. Now, 67 years after women won the right to

vote, Xiomara Castro Sarmiento Zelaya is promising to be a president

of the people and to restore Honduras’s constitutionality and

rule of law. It promises to be a new era for women, of all races and

ethnicities, and LGBTI communities. I am excited and hopeful. So is

my mom. My grandmother would have been, too.

This

commentary was originally published by NACLA