Invoking

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

in mid-December, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis announced new legislation

that allows parents to sue schools for teaching critical race theory.

“You think about what MLK stood for. He said he didn’t

want people judged on the color of their skin, but on the content of

their character,” said DeSantis, a political ringleader in the

latest chapter of the United States’ culture war. In using a

quote from Dr. King to justify an attack on curricula that uplifts

racial justice, the Republican governor inadvertently created a

strong case for why critical thinking on the history of race and

racism in the U.S. is necessary.

History

professor Robin D. G. Kelley

is all too familiar with the sort of contradictory statements like

those DeSantis spouted. Kelley, who is the Gary B. Nash Endowed Chair

in U.S. History at the University of California, Los Angeles,

explains that he “came into the profession at the height of a

battleground over history, in the 1980s, with the war on political

correctness.” And although he’s lived through decades of

conservative-led attacks, like those by DeSantis, he describes the

2020s as “dangerous times.”

The

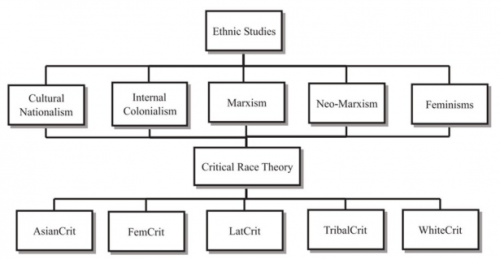

Origins of CRT

Kelley

sees right-wing attacks on CRT—what he considers an umbrella

term for the teaching of “any kind of revisionist or

multicultural history”—as a measure of the success

communities of color and progressive parents and teachers have had

after pushing for years to ensure that educational curricula reflect

racially and ethnically diverse classrooms.

The

most recent movement for such education can be traced to the Freedom

Schools

of the 1960s, which, in the words of educators Deborah Menkart and

Jenice L. View, “were intended to counter the ‘sharecropper

education’ received by so many African Americans and poor

whites.” In a civil rights history lesson created for Teaching

for Change,

Menkart and View explained that the education offered in nearly 40

such schools centered on “a progressive curriculum …

designed to prepare disenfranchised African Americans to become

active political actors on their own behalf.” In 1968, after

months of pressure from student activists, San

Francisco State Universityestablished

the first College of Ethnic Studies in the U.S.

A

movement to offer ethnic studies courses in public schools, including

colleges and universities, has gained traction nationwide. Such

education is now standard fare as part of required college courses.

California remains on the cutting edge of multicultural education,

becoming the first state in the nation, in October 2021, to require

high schoolers to enroll in ethnic studies courses

in order to graduate.

Leading

African American scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, a law professor at

UCLA, coined the term “critical race theory” and

co-edited the book of the same name, which published in 1996, to

define race as a social construct and provide a framework for

understanding the way it shapes public policy. Crenshaw explained in

a New

York Times

article that CRT, originally used by academics

and social scientists

to analyze educational inequities, “is a way of seeing,

attending to, accounting for, tracing and analyzing the ways that

race is produced … the ways that racial inequality is

facilitated, and the ways that our history has created these

inequalities that now can be almost effortlessly reproduced unless we

attend to the existence of these inequalities.”

Understanding

the Attacks on CRT

Critical

race theory is precisely the sort of nuanced educational lens that

Crenshaw, Kelley, and others use in their courses and that has White

supremacist forces up in arms. Attacks against CRT are taking the

form of multi-pronged legislative

restrictions and even bans,

as well as firings

of teachers

accused of teaching biased histories.

Kelley

sees conservatives like DeSantis working relentlessly to eliminate

any education that actually reckons with the history of American

slavery, the genocide of Indigenous peoples and dispossession of

their lands, sexism and patriarchy, and gender and gender identity.

Reflecting again on the ’80s, he says the attacks on ethnic

studies, culture, and race didn’t only come from the Right. “In

fact,” he says, they also came from “liberals, from the

Left,” and from those saying “we’re not paying

enough attention to class [struggles].”

Kelley

cites “classic liberal fatigue” against ongoing demands

for racial justice, which he encapsulates in responses such as, “We

already gave you some money, we already gave you this legislation,

what else do you want to ask for? Why are you criticizing us?”

A

case in point about how liberal figures are joining the right-wing

war on CRT is a new venture called the University

of Austin,

Texas, created by a group of public figures led by former New

York Timeswriter

Bari Weiss. Weiss, in an op-ed

in the Times,

cited unpopular ideas, such as “Identity politics is a toxic

ideology that is tearing American society apart.” She expressed

dismay that such an opinion—generally considered a racist

one—is shunned by many academics.

To

counter what Weiss considers censorship, UATX’s founders say

they are devoted to “the unfettered pursuit of truth” and

are promoting a curriculum that will include the “Forbidden

Courses”

centering on “the most provocative questions that often lead to

censorship or self-censorship in many universities.”

As

if to underscore Kelley’s warning about liberals joining the

right-wing culture war, the nascent university’s board

of advisors

includes figures like Lawrence Summers, former U.S. treasury

secretary and former President Barack Obama’s economic adviser,

who is a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the left-leaning Center

for American Progress.

A

Counter to the Moneyed Interests Backing CRT Attacks

Kelley

sees a difference between earlier battles over political correctness

and those centered on CRT today. “The Right has far more

political weapons. They are actually engaged in a kind of McCarthyite

attack on school teachers, the academy, on students, on families, and

passing legislation on what’s called critical race theory,”

he says.

Right-wing

narratives have cast the backlash against CRT as a grassroots

effort

led by parents concerned about bias in their children’s

education. But secretive and powerful moneyed interests are at work

behind the scenes. The watchdog group Open

Secretsrecently

exposed how right-wing organizations, like the Concord Fund, are part

of “a network of established dark money groups funded by secret

donors … stoking the purportedly ‘organic’

anti-CRT sentiment.”

Additionally,

CNBC reporter Brian Schwartz exposed

how “business executives and wealthy Republican donors helped

fund attacks” on CRT and that it is expected to be a

centerpiece of the GOP’s campaign ahead of the 2022 midterm

elections.

In

contrast to the politically formidable and well-funded forces arrayed

in opposition to CRT, the Marguerite

Casey Foundation

each year gives out unrestricted funds to prominent thinkers, like

Kelley, to counter “the limited financial resources and

research constraints frequently faced by scholars whose work supports

social movements.”

The

Foundation chose six scholars whom it describes

as doing “leading research in critical fields.” Those

include abolition and Black, Latino, feminist, queer, radical, and

anti-colonialist studies, which are precisely the fields that are

anathema to anti-CRT forces.

Kelley,

who was named one of the foundation’s 2021 Freedom Scholars,

agrees that such funding can help level the playing field for

academics working to expand educational curricula that challenge

White supremacist and patriarchal histories.

Going

beyond defensive countermeasures against the right-wing attacks on

CRT, such awards can help fund the study of histories of social

justice movements that are thriving. “We’re beginning to

break through the narrative of civil rights begets Black Power,

[which] begets radical feminism,” says Kelley, citing

grassroots change-making groups that have been active over the past

50 years through today and that have not gotten enough attention,

such as the Third

World Women’s Alliance,

the Boggs

Center,

the Combahee

River Collective,

The

Red Nation,

and INCITE!

Women of Color Against Violence.

“Just in the last two decades, we’re seeing so many

amazing movements whose history is being written as we speak,”

says Kelley.

He

is heartened by what he calls “new scholarship” that is

“thinking transnationally, thinking globally, and moving away

from a focus on mostly [White] male leadership and thinkers,”

giving way instead to the “political and intellectual work of

those who have a different vision of the future.”

This

article was produced by Economy

for All,

a

project of the Independent Media Institute