In

countries across the capitalist world, trade

union movements are being challenged to their

very core by the growth of right-wing populist

and neofascist mass movements. What makes this

situation especially dangerous is that labor

unions and supporters are facing not just

maniacal leaders or even military juntas, but

a strengthening political alignment

between segments of the capitalist class and

these same right-wing social movements.

The

post-Cold War rise of right-wing populism

overlapped with, but had different roots than,

neoliberal authoritarianism which, over the

second half of the 20th century,

curtailed the growth for left and progressive

politics, while the ability to protest became

increasingly limited. During this period,

capitalist states reduced their role in any

degree of wealth redistribution and enhanced

their repressive apparatuses.

Right-wing

populist and authoritarian movements arose in

different countries in very different ways. In

the United States, their rise preceded the

emergence of neoliberalism as a growing,

reactionary response to the progressive social

movements of the 1930s

and following decades. This later combined

with the rise of neoliberalism in the 1970s

and the stagnation of living standard for the

average working person.

Neoliberalism

also brought with it increased wealth

polarization and, therefore, panic within the

middle strata of society resulting in the

classic dilemma for the middle strata: were

they going to be crushed between the rich and

the poor or was there another solution?

Neofascism

(or “postfascism”)

has emerged as an outgrowth of loosely

entwined right-wing populist movements. In

some cases, neofascism arose through

a revolt against the impact of

neoliberalism, and in other cases as revolt

against the welfare state. In either case,

what has come to unite these various movements

has been revanchism, i.e.,

the politics of revenge and resentment by

those who believe something has been taken

from them by the “other.”

It

is here that race, sex, gender and religion

become critical categories for identifying

scapegoats. Revanchism has been accompanied by

the politics of the mythical return to

a better time — a time that allegedly

existed where everyone knew their place in

society and “we”

all lived comfortable lives.

The

modern trade union movement arrived at

a detente with the dominant sections of

capital in most countries following World War

II. This does not mean there was an absence or

abandonment of class struggle, however, rather

that class struggle shifted in form. In many

cases it shifted to other-than-union working

class organizations, or it took the form of

struggles by segments of the working

class — women, migrants, workers of

color — resisting various forms of systemic

economic and non-economic oppression.

Whether

through co-determination, tripartism, or

industry agreements, the leadership of much of

organized labor in the United States concluded

that “peace

in our time” had arrived, despite the fact

that the larger working class, particularly

among marginalized populations — frequently

lacking collective organization and the right

to freely organize, protest or bargain — were

experiencing the underside of this brokered

peace between the labor movement

and capital.

Nationalism

meets revanchism

Up

until about a decade ago, trade union

movements in the advanced capitalist world

largely downplayed the significance of the

rising right-wing populist and neofascist

movements. To the extent to which it was

acknowledged, there was a tendency to

treat the question of right-wing

authoritarianism as a marginal movement.

In the 1980s,

the National Education Association took steps

to educate its members about the dangers of

white supremacists and other right-wing

authoritarian formations which had become very

active in the Midwest and North West. Among

the larger trade union movement, such actions

were the exception, not the rule.

Neofascists

claim to be in opposition to “globalism,”

whereas much of the established trade union

movement often seems to have accommodated

itself to neoliberal globalization, even when

unions are critical of certain elements of

neoliberalism. For the far right, globalism is

only partly about the globalization of

capitalism, but more commonly refers to the

migrant surge of the last 40 years,

relocation of jobs overseas and what is seen

as the disappearance of borders. Globalism,

for those on the far right, is about the

breakdown in parochial ways of thinking and

acting. As a result, nationalism becomes

the flag to protect not the nation state, but

the old ways — traditional values. Nationalism

becomes linked with revanchism and the idea

that these old ways of doing things have been

threatened and the possibility for a good

life has been taken away from the

average person.

To

the extent organized labor failed to pay

attention to shifts in the methods of work and

in the workforce itself — and particularly the

growth of casualization and the informal

economy — it appeared to its critics to be

a movement for an “elite,”

though it is highly unlikely that most trade

union members would think of themselves

as such.

Despite

electoral-political engagement by trade

unions, there has been a stark reluctance

by most union leaders and leadership bodies in

the United States to explicitly name the

fascist threat, or the broader threat posed by

right-wing authoritarianism. This aversion

must be situated in the context of the chronic

illness that has befallen the U.S. trade union

movement — and, for that matter, many other

trade union movements in the advanced

capitalist world.

This

illness amounts to a decline in the face

of the neoliberal offensive and a failure

to accept that the terms of the post-World War

II labor/capital truce no longer hold. In

fact, unions in both the public and private

sectors are currently being obliterated by

more politically-reactionary segments of

capital. Rather than pushing the limits on

democratic capitalism, the trade union

movements have up to this point largely

accommodated themselves to defeat, albeit

a slow-moving defeat.

Neofascism

sees the trade union movement as its enemy

while at the same time trying to appeal to the

working class who make up labor’s membership.

With

the rise of right-wing populism and

neofascism, the crisis has become acute.

Neofascism sees the trade union movement as

its enemy while at the same time trying to

appeal to the working class who make up

labor’s membership. However, to win over this

base, the far right is harkening back to

previous pseudo pro-worker appeals by

embracing racist, sexist, homophobic,

xenophobic politics that can present as being

in the interest of everyday

working people.

Toward

an antifascist labor movement

The

response of the global trade union movement to

these efforts has been uneven at best. On the

one hand, an international

alliance of antifascist unions was

established through the work of Italy’s

Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro

(CGIL, the left-wing trade union

confederation). Similarly, a 2022 report

commissioned by the German trade union

movement, the Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund

(DGB), indicated that there has been

a high level of educational work

conducted by European labor federations and

confederations to raise awareness regarding

the threat from the far right. These are

promising efforts, but don’t yet amount to

large-scale active campaigns conducted against

the far right (whether in the workplace or

communities) as well as campaigns against

forms of discrimination and oppression that

are often exploited by these same forces.

In

the United States, efforts have been equally

uneven. Until very recently, almost no

anti-far right educational efforts were being

conducted within the union movement. Though

there have been some educational programs that

have focused on racism and sexism, even those

are more often than not very incomplete. The

reluctance to touch on matters that most union

leaders perceive to be “divisive”

has repeatedly led to a retreat into the

focus on the economic — including militant

economic rhetoric and struggles — as if that

will serve as the unifying force of union

members. Despite decades of efforts in that

direction, when facing down a far-right

threat, they rarely succeed.

At

the same time, principally in response to

President Donald Trump’s second

administration, resistance efforts have been

taking place. In the federal sector, rank and

file union members led by progressive local

union leaders established the Federal Unionist

Network (FUN) as a means of coordinating

fight-back efforts to the attacks on federal

sector workers by the Trump administration.

This has been especially important in light of

the anemic state of most federal

sector unions.

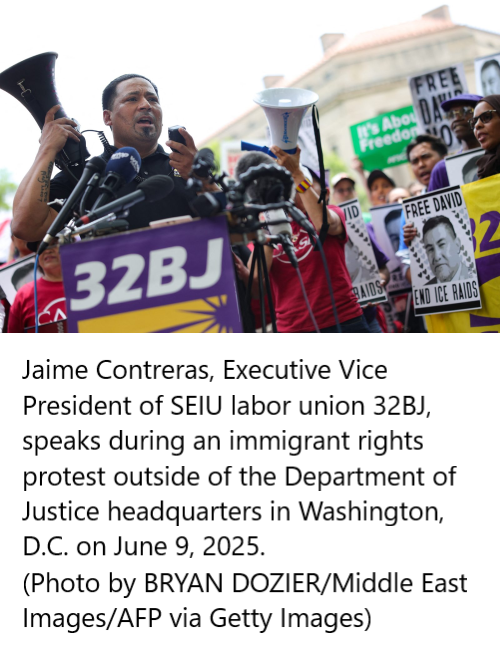

Recently,

the Service Employees International Union

(SEIU) displayed great courage when one of its

key leaders in California was assaulted and

arrested during a protest against

Immigration and Custom Enforcement (ICE) raids

and kidnapping of immigrants. SEIU and other

unions mobilized their members, and those of

other unions, to demand their leaders release

and to oppose the ICE raids.

The

Chicago Teachers Union, along with other local

unions, helped organize nationwide May Day

protests this year and is seeking to build

continued protests against anti-worker,

anti-democratic practices by the Trump

administration. And, in higher education, the

American Association of University Professors,

the American Federation of Teachers and the

National Education Association have all

engaged in active protests and

other mobilizations.

Yet,

with the exception of Standing

for Democracy,

a newly formed strategy center and

mobilization group, and the recently-founded

group Labor

for Democracy,

there have been limited efforts to

contextualize the current attacks in light of

the growth of a mass fascist movement. In

that sense, much of the current resistance

work, as powerful and as essential as it is,

misses the point that these are not normal

circumstances. These are not fights against

the expected assaults by conservative,

neoliberal forces. The trade union movement is

in a fight for its very existence, and

for the existence of even a semblance of

democracy and economic justice.

Throughout

modern history, in U.S. trade union circles,

it has been suggested that building

a militant struggle for economic justice

will unite workers and defeat the far right.

Yet the fact remains that the trade union

movements in Italy in the 1920s and

Germany in the early 1930s attempted

just that course and were met with disastrous

political results.

There

is no room for silence or middle ground. Trade

unionism must either be anti-fascist, or it

will be nothing at all.