|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Custom Search

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

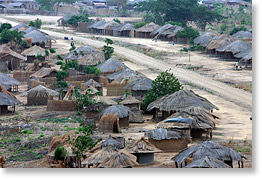

Diamantino Nhampossa is executive director of the Uni„o Nacional de Camponeses (UNAC) / National Peasants' Union of Mozambique and a member for Africa of the International Coordinating Committee of La Via Campesina. La Via Campesina is an organization of organizations, part of a global movement of peasants, family farmers, indigenous and landless people.The interview was conducted (and later edited) by Nic Paget-Clarke for In Motion Magazine on October 18, 2008 during the 5th International Conference of La Via Campesina. The conference was held at the FRELIMO Party School in Matola, Mozambique. Nic Paget-Clarke: Do you come from a farming background yourself? Diamantino Nhampossa: My grandfather and my parents were small farmers. My first education was to grow up in farming, which means in the farming rural areas. A lot of young people leave the rural areas here because there are not enough schools. To go for higher education you need to leave your rural area to go to an urban area school. That is what happened to me. I had to leave my home area to come to Maputo to study. Nic Paget-Clarke: Where is your home area? Diamantino Nhampossa: Itís in Inhambane. Itís a place which is located 500 kilometers north of Maputo. Inhambane is a province but there is also a town called Inhambane in which I grew up. Nic Paget-Clarke: What sort of farming did your family do? Diamantino Nhampossa: Generally, farming here and in my family is everything: with animals, cows, goats, chicken, ducks; and also fruits, all different kind of fruits -- tropical fruits, papaya, keppel, oranges. And then we have coconuts and other crops like maize, peanuts, beans, which are part of the needs of everyday life. Basically, we produce for local consumption, not for selling. It is for family consumption, to respond to the needs of the family. There is a little surplus and that goes to the market. Nic Paget-Clarke: And this was family based or it was a cooperative? Diamantino Nhampossa: It was family based. 1987: The World Bank/the IMF and UNAC Nic Paget-Clarke: Can you please tell me a little about the history of UNAC? Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes. Historically, the movement of peasants and small farmers started right after independence (June 25, 1975) under the government. The government created a lot of associations and cooperatives under the centrally-planned economy, but there was no national platform of these associations until 1987. 1987 was the year that the IMF (International Monetary Fund) and the World Bank came into the country, when we got the first loans from these institutions and accepted all the conditionalities of liberalization, of privatization, of everything. The government reduced intervention in the economy, which means it reduced its support of small farmers and associations and cooperatives. Under that situation, the leaders of these associations and cooperatives organized a national conference to discuss what would be the future of the farming community after 1987. They decided to create a national platform of farmers, which is UNAC.

At that moment, there were two basic objectives. One of them was representation of the farmers before the government, fighting for rights to land, the right for subsidies, the right for support to produce. The other one was to implement development projects in the rural areas. From that moment on, it (the government) declared that the private sector would have the most important role in developing agriculture, but we did not have any kind of private sector in agriculture. There was no funding that would help the private sector to work in agriculture. Agriculture was not attractive. The private sector that we had was more traders importing goods from outside to sell, but not in production. There was not any kind of support for agriculture and we, as an organization, decided at that moment that the organization should play a role in looking for funding to develop agriculture projects in the associations and cooperatives. Today, these are the two pillars of the organization: representation and implementing local rural development projects. Nic Paget-Clarke: What do you mean by projects? Diamantino Nhampossa: Projects are specific issues, problems that small farmers identify in their own community and need to decide on specific solutions for; to define a strategy of how they are going to implement the solutions they have for those specific problems. That includes looking for resources, looking for funding -- wherever it can come from, from NGOs, from donors, or from government -- to respond to that specific problem. Letís say they have a river and they cannot use it for irrigation. What they need is a small dam, or a pump, or whatever. They work together in order to obtain that objective of putting the irrigation system into function. That would be the kind of a project that we are talking about. Nic Paget-Clarke: Would those resources sometimes be internal to that association or is it always looking for external resources? Diamantino Nhampossa: The first source of the resources is internal. It would be the contributions of the members of the specific cooperative or association. But we donít put aside the possibility of looking for those funds outside -- taking into consideration that some of the funding that comes from outside comes with a lot of conditions and they can endanger the ownership of the process and create dependency. The most important source of the funding for the projects is the local capacity to raise, to share the resources of the funding. Nic Paget-Clarke: What is the difference between an association and a cooperative? Diamantino Nhampossa: Today, it is not clear, even in our organization in Mozambique. Why? Because during the centralized economy the government created a lot of cooperatives and these cooperatives suffered a lot of intervention from the government officials and people did not like it. Although they liked, or they see, association and cooperation as a way to resolve problems, they did not like the model that was being implemented, in terms of cooperatives in Mozambique. So, they donít like the word cooperative, and sometimes they call themselves associations when they are actually cooperatives. But, we usually distinguish associations from cooperatives when a cooperativeís economics are more for social purposes -- it is a profit organization but the profit is directed to social purposes. An association is a non-profit organization; it is only sharing ideas. They are not supposed to profit from work. A cooperative does profit from work. Nic Paget-Clarke: And then they distribute that profit among their members? Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes. Or they build a hospital for themselves, or a school. It is for common use. The socialist period in Mozambique Nic Paget-Clarke: How do you sum up the socialist period in Mozambique? What were those years? Diamantino Nhampossa: There were almost ten years of socialism. They were very important to affirm the national unity after almost 500 years of colonization. It was the first opportunity when people were feeling that we have lives, we are independent, we can think by ourselves. We can determine our own future without interference from outside.

The affirmation of nationality was very important. The unity of the different tribes was very important. It was only ten years but we can still feel it today. Things like what is happening in Kenya would never happen here, at least in the next twenty years, because of those ten years. We donít see the tribal differences. We donít talk about race. If you look at our statistics you will never see ďHow many blacksĒ or ďHow many whitesĒ or ďHow many ChanganasĒ, or ďHow many TongasĒ. We always talk about people in the country and thatís finished. We donít make these differences. The differences only come in terms of class: who owns more and who owns less. We can talk about that. It is important to see where it is distributed. That was very important. There were also very difficult moments because there was the Cold War and we were under pressure from the apartheid system and Ian Smith in Zimbabwe, in Rhodesia. It was a lot of pressure. We were labeled as a communist country, therefore something to be finished. It was difficult in that sense. Some of the things that happened, like nationalization of the church property, were the stains of the process. Those were the difficult things that happened. Also, most people did not like to be organized as cooperatives. They would like to be in a cooperative because they wanted to be, not because they were obliged. People were being moved from one place to another without consent. Those were some of the difficult moments of those ten years. But you can also see that people experienced equality. They experienced what equality means. For example, you wouldnít feel that the minister is more important than I am because I am just a simple citizen. It was transparency in terms of the salary of the minister, how the wealth was distributed. It was clear. There was no corruption. There was no crime. There was nothing. Those were very important years, although there were some setbacks, related to the Cold War, and because of that a war was waged.

Nic Paget-Clarke: The RENAMO war? (ResistÍncia Nacional MoÁambicana) Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes. Basically, to destroy communism in the country. That was the idea. It was not a political movement to change the situation, it was just a destabilization war to end the socialism in the country. Thatís why even the RENAMO party today doesnít have expression. You donít understand what is the ideology. Are they left wing? Are they right wing? What is their proposal to society? It is not clear. Although, FRELIMO also has the same problem today. It is not clear, in terms of strategy, where they want to take the country. So, we had this war which was related to the fact that we were putting a lot of stress on being independent, to make our own decisions and be sovereign. Those things were not likeable to some of the powers.

From the perspective of national interest to privatization Nic Paget-Clarke: Why did socialism end here? Diamantino Nhampossa: One thing is, we didnít actually reach socialism, anyway. We can talk more of nationalism. We are talking about socialism because those who financed the struggle for liberation were people from the East, the Chinese, the Russians, the ones who built this building here, the Germans, the Democratic Germans (editor: the FRELIMO Central Party School where the conference was held). Thatís why we went also to go and bring the ideas of socialism, because they were the ideas that were being discussed by Vietnam and other countries that supported our struggle. There was more nationalism. In any case, we reached the situation where we were bankrupt because the system in the East was crashing. The support that came from the Soviet Union, the support that came from China, it was reduced very much, and we became bankrupt. So, Samora Machel (the first president of Mozambique) had to look for solutions from the perspective of national interest. The solutions could come from anywhere. It didnít matter where. Thatís why he visited (U.S. president) Ronald Reagan in 1984, trying to commence some kind of negotiations with the West to finish the problems that we had. Thatís when the negotiations to become members of the IMF and the World Bank started. We ended socialism, they ended it, trying to look for solutions for the economy which was very much down -- because of the war, because of the pressures from the apartheid system, from the Rhodesians. In that period, people were going to the U.S. looking for solutions for the country, now they are not thinking that way. They think that the correct way of doing things is using the neoliberal model. That was not the thinking in that period. If we are going to look for resources to make the country grow, develop agriculture, to provide basic resources for the people, we go to the West looking for money for the private sector, for big investments, not for the development of the people as such. There was clarity in those days, today there is no clarity. Itís just looking for money, just business. Not looking for solutions for the problems that the people are facing. Thatís why you see the gap between the rich and the poor. Itís very big today. It was almost zero in the past but today it is very big. We have a very rich private sector here, while the vast majority of people have barely anything to eat. They live in very bad conditions. No access to health and education. All the schools have been privatized. The universities have been privatized. Public services, water, electricity, gas have all been privatized and become so expensive that the poor people are never going to be able to access them. Nic Paget-Clarke: So socialism was not run in a sustainable way? It relied on outside help? Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes, it was basically that. It relied very much on the outside world. Also, we inherited a system from the colonial period that had to crash first before it could rise again. All the capitalists were chased away. Or they just left because they did not concur with the socialist model. Some people destroyed, sabotaged the companies. Nic Paget-Clarke: The Portuguese? Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes. Thereís a refinery nearby which was a very big one. There was a lot of sabotage. They spoiled it completely. That happened a lot. We inherited problems from the colonial period which had to be managed. It took only five years for the economy to go down. It (the colonial system) relied very much on the support coming from the English government. The English government gave a lot of money to the Portuguese, foreign support to the Portuguese colony: the gold mines in South Africa, the contracts with the Portuguese. There was a lot of gold coming into the country. All these things were cut when we became independent. We inherited a very high debt. It (the socialist period) was unsustainable because it relied very much on external donations. We did not have time, I think, to start working before the collapse of socialism in the world. Although we had a lot of support from Cuba, a lot of support from the Soviet Union, all of them started having problems and we were very much dependent on them, even to produce what we were exporting. We relied on their machines. It was, as you say, very much unsustainable. It was difficult. Nic Paget-Clarke: And the neoliberal period is not very sustainable either? Diamantino Nhampossa: Of course. There is no better evil. Evil is evil. The neoliberal model came in 1987 and took away all the industries. All the industries were privatized. The cotton industry, the textile industries, tea industries, basically those industries were processing agricultural crops and were all finished, privatized under the support of the IMF. And then they never functioned. None of them is functioning. Nic Paget-Clarke: Did they go to Mozambican private owners or multinationals? Diamantino Nhampossa: They were generally given to Portuguese and other multinational companies. They never operated for more than five years. All of them just collapsed, even after privatization. We started relying very much on imports, imported foods.

And the government is not relying on taxes that we pay. We are relying very much on donations -- sixty percent of our budget. When we started, 40 percent of our budget was coming from outside, and it grows every year. Now we are at a level where 60 percent of our budget comes from donations. Also, perhaps 30 percent of our budget comes from multinational companies. Thereís a big plant just around the corner from here, an aluminium production plant that doubled our GDP (gross domestic product) after it started operation. The Coca Cola company and others contribute to exports, so they raised the income of the budget. In other words, we, who are citizens, we are only contributing 10 to 15 percent. We are completely dependent on external support. ďOne of the fastest growing economies in the worldĒ Nic Paget-Clarke: You mention multinationals. You say they are increasing the GDP and thus the national budget, but doesnít all of the profit actually go out of the country? Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes. We are still very dependent and the powers of the West donít care about the fact that we are increasing dependence. They even want us to be dependent so that we can accept all the conditionalities of opening the markets. Nic Paget-Clarke: So, just to make sure I understand this. When people say, ďNow, under the IMF policies, the GDP is increasing,Ē and, ďMozambique is starting to do well,Ē thatís strictly a numbers game because most of the profit goes out of the country, leaving you with nothing? Diamantino Nhampossa: Definitely. We have been told that Mozambique is one of the fastest growing economies in the world. But you donít feel that in the people. You donít see people changing their lives. The lives of the citizens have become worse and worse. Yet the numbers are so attractive. The World Bank has been praising us. It is actually an interesting fact that here, in February, we had a visit from the president of the World Bank. He left on the fourth of February and he said, when he was going, ďThis is a very exemplary economy. You have been performing so well.Ē But, on the fifth, it was announced that the price of public transport would increase 50% and there were riots everywhere in Maputo. The city stopped. A lot of violence. Very big riots. Some people got killed. Police cars were burned. People were exploding from so many problems that they were feeling. And these people also include the police. The police who were supposed to stop the riots. The policeman has to walk for a few kilometers before he reaches the police station to take the gun and go to protect the people. He is also part of the suffering in society. When you say you have to increase your fee for public transportation, he is also very much affected. That is why it was so difficult to stop the riots around town because the police also did not care. Their salaries are very low. Thatís just an example of how this is a fast-growing economy and yet the peopleís lives are getting worse and worse. Food is expensive. School is expensive. And when I say school is expensive, you are not supposed to pay for the public schools, but the teachers are badly paid, in terms of salary. There are no laboratories in the school. There are no books. You have to buy all your books. And sometimes you have to pay the teacher to give you a good mark. Life is really very difficult for the public sector. All this is because the IMF says the government should reduce public expenditure to avoid inflation. The salaries of the teachers and nurses are very much contained. When you go to a hospital it is a very beautiful building, painted, and this of course has been a loan from the World Bank to make this building. But inside there is no nurse, no equipment. There is nothing. These are the contradictions of this growing economy, but yet extremely dependent. It could be a source of social instability in the future. Nic Paget-Clarke: UNAC believes in an alternative method, I take it. How would you describe what you are doing to try and change that? Diamantino Nhampossa: We are organizing as farmers to defend our own interests. Nic Paget-Clarke: What percentage of the population are farmers? Diamantino Nhampossa: 80 percent. 15 million.

Nic Paget-Clarke: And how many are represented by UNAC? Diamantino Nhampossa: The ones who are organized, and we can give you the names of the organizations, are only 65,000. Our members are scattered throughout the country but a lot of them are not part of the movement. Some of them are sorted by NGOs in projects which never end and never change the lives of the people. Poverty here is sometimes a source of income for some organizations. They keep writing project proposals, getting the money, and then spending it on administration but nothing ever goes to the rural areas. What we do as an organization is make sure that the local organizations, associations, grassroots organizations, have got power to look for solutions to their own problems. We do that promoting a lot of meetings, organizing a lot of training, a lot of exchanges, to strengthen the farmers to be able to look for solutions for their own problems. We do this taking into consideration the Via Campesina model for development, which is food sovereignty, (it) is a model which can be accessible to the rural poor in this country. The model that is being proposed of mechanized agriculture, with very expensive inputs like fertilizer, chemicals, and other things, that is not sustainable for our small farmers. But the model proposed by Via Campesina, which is food sovereignty, is the one that has been practiced by small farmers for years. Nic Paget-Clarke: When you say years, is that generations? Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes, generations. Most of them are still using the same method as in the past. My grandmother, she is around 85 now, I grew up on that farm, she produces food to eat. Today, when I come back, she still gives me a bag of maize or a bag of peanuts. She still is producing on the same farm. She is using sustainable models of production. The soil is not being spoiled and thatís the source of her health. Her health is pretty good because of that. She doesnít know what a hospital is. She doesnít know what a doctor is. But she is going to her nineties because she is related to that land, to the products that the land gives. This agriculture, we need to put it as a solution, as a political solution, because today many people put it as an old fashioned way of doing agriculture that is slow and doesnít bring profit. UNAC is trying to bring it back and say, ďThis is the solution to the problems. This is the solution for the food crisis today. If all our farmers were able to produce their own consumption, we would not have to face this problem of doubling the price of rice or other products. This is the solution we are bringing to the organizations that we are organizing in our meetings, and our training, to change the situation. Also, this is the solution we are putting forward to discuss with our government, the Minister of Agriculture -- talking about research extension services for the farmers, small infrastructure, irrigation systems, credit schemes, subsidies for small farmers. We are always talking about this with the government. Nic Paget-Clarke: You are presenting the solution to the farmers but you are also presenting it to the government? Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes. The main thing is it is actually the farmers themselves that discuss these things with their local governments. When we say ďweĒ, at the central office, the discussion with the Minister of Agriculture is at that level. But the discussion is also done through our members in the rural areas with the local governments, using this perspective.

Nic Paget-Clarke: In the conference press kit, it lists the objectives of UNAC and the first one listed is ďautonomy of the local communitiesĒ. What does that mean? Diamantino Nhampossa: Autonomy and sovereignty of the local communities means that the farmers in their own communities are able to satisfy most of their needs. It does not mean closing themselves up to the outside world but it is to use their resources to the best and satisfy their needs maintaining biodiversity, protecting biodiversity, and connecting to other societies in other communities to share in solidarity, to share knowledge, experience, exchange seeds - that is also very important. All the communities have to be able to affirm that they have their own culture, their own knowledge, their own capacity to produce so that they can share with others. We donít see that some communities have more knowledge than other communities. Nic Paget-Clarke: How big is a community? Diamantino Nhampossa: It depends very much, but our communities would be something like 500 to 200,000 people. Nic Paget-Clarke: Whatís the relationship between this autonomy and democracy? Diamantino Nhampossa: The relationship is very much complex. The organization size is very much complex. There is traditional society that keeps traditional chiefs and they have some kinds of commonalities and linkages. And the linkages are based on blood -- the name of the family, of the clan, of the tribe. They have some kind of traditional bonds that link them and there is a chief of that specific place. But there is also a new kind of organization that was started by the government, (started during the socialist period) which is also active. Nic Paget-Clarke: What is that? Like a community council? Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes, we call them barrios. There is a secretary for the barrio, and other functions. Nic Paget-Clarke: Those are elected? Diamantino Nhampossa: No, those ones are indicated by the central government. Nic Paget-Clarke: To this day? Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes. This year we are having elections for the municipalities, but that is only in 40 geographic spaces in the whole country. Very little. Now, there is another level -- of associations. Those are our members. Those are linked through economic, social situations in which they want to solve as a group, so they organize themselves in that way. And sometimes all these things intermingle, these layers intermingle. It is very much complicated for the common people. The simplest way to hear that I belong to something is to be part of an association. An association has a minimum of ten people and the oldest one, the maximum, may have 200 people. There is direct benefit that they feel from being part of this specific association or cooperative and they dedicate a lot of their lives to this thing. Most of our members are in those associations and they spend their lives working in the association, joining together, discussing, looking for resources, advocating for their rights. But the other levels are so much complicated. Nic Paget-Clarke: The other levels are left over from previous times? Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes. They are problems and have been messed up by colonialism, by socialism. It is so difficult to manage those levels, although, because of political interests, they are still kept. It is through these layers that the government works, or appears to be. They are political and interventive. They can take decisions in the name of the community. They are more used for political interests. Nic Paget-Clarke: They represent the state? Diamantino Nhampossa: To some extent. Nic Paget-Clarke: Whereas the people are involved, on their own, through these associations? Is that accurate? Diamantino Nhampossa: Thatís it. The associations feel more represented by the people whom they have elected. Nic Paget-Clarke: And that is what you mean by autonomous? Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes. Nic Paget-Clarke: And if one community wants to talk to another community, they would go from association to association? Diamantino Nhampossa: It varies very much. It is not homogenous. It depends, from place to place. You will find a place where the associations have some kinds of linkages to the system that is set by the government, the barrios. It could happen like that. Associations are very important spaces that the government also uses to dialog with the small farmers. When there are associations, sometimes itís easy. Thatís why in some instances they create associations, which is not correct. As well as some NGOs, they create associations because they want to organize people into groups to facilitate the giving out of goods. Itís easy to bring people together to discuss within the association, because is not political. It is more difficult to bring people when you talk about a barrio, because people start to be suspicious. People donít speak freely in those levels of organization. To increase the conscience, responsibility Nic Paget-Clarke: How would you assess the progress in creating the UNAC type of associations and cooperatives? Diamantino Nhampossa: I think there is a lot of change. The small farmers are becoming more clear of what is their role in the society. Thereís so many small organizations being created every day by the farmers themselves. We canít even know exactly what are the numbers because the groups are created by themselves and are becoming stronger and have expression and are very much dynamic in the rural areas. This is visible especially in this last three years because the government established the fund, a local development fund, which can be accessed by associations or the private sector in specific districts. Small associations are appearing to be the most active in accessing this funding and using it for the production of food. This is interesting because even the private sector is being overwhelmed by the associations because individual people should be more efficient than a group of people. It is easier for me, myself, to go and get the money and implement something. But ten people are more efficient than one, at this moment. Ten are well organized to get the funding, to implement and distribute. They are appearing to be better organized. There is a history of twenty years of organizational association, of struggling, of contributing to increase the conscience, the responsibility, of the farmers in the changing of their own lives. Nic Paget-Clarke: Would you say that what these associations are doing is an example of building an alternative world? Diamantino Nhampossa: Not yet. We, the associations are not in complete control. They are not able to control everything, even in their own community. Nic Paget-Clarke: Because of these other factors? Diamantino Nhampossa: The political situation is very tense. But if you look back there has been so much change. There is a lot of respect from outside parts, government, and others, in relations to these associations. They appear to be a little bit more powerful than they used to be. Agroecology as a political affirmation Nic Paget-Clarke: Do you use agroecology? Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes, we use agroecology. Our wish is to have it done in a very systematic way. We are waiting now on a training strategy for agroecology to make sure our farmers implement this principle, or way of production, in a more systematic way. Today they are practicing it because no one came to propose that they use a special fertilizer, chemical additive, or a special seed, or whatever. The danger of them changing from their way of production today is bigger because agroecology is not being put in a very systematic way as a very political affirmation of what agriculture should be for the small farmers. We still have a long way to walk, in terms of informing people, giving them the political strength to defend agroecology, or defend agriculture as they are practicing it today. Nic Paget-Clarke: Thereís a big move to bring the Green Revolution here? Is that true? Diamantino Nhampossa: Thereís even a strategy for a Green Revolution in Mozambique. We even participated in the definition of this Green Revolution strategy. Nic Paget-Clarke: You did? Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes. We highlighted the negative effects of the Green Revolution in India and Mexico. We said it was very important to take into consideration these aspects and not repeat them in our country. For us, we donít care about the word itself, which is ďGreen RevolutionĒ. What you do is try to explain what agriculture is for us, and should be for us, and people are going to feel that is opposite to the Green Revolution. We are not using the word or the sentence, ďNo to the Green RevolutionĒ, but we are putting things in such a way that people can see that this is not the Green Revolution. In this strategy, you will see that it is agroecology, the strategy that we propose, that was written by the government. It is, basically, agroecology: diversity, in terms of seed; no use of chemical fertilizer; no use of mechanization. Nic Paget-Clarke: That is what the government is now promoting? Diamantino Nhampossa: That is what the strategy says, the strategy that was approved. But its actual implementation is different because the main players of the Green Revolution, Bill Gates, Rockefeller (Foundation), all these people, believe in mechanization of agriculture, believe in chemical fertilizers, believe in big irrigation systems, and the money they have to give our government is to buy those things. To buy the tractors. To buy chemical fertilizers. It is not money to subsidize more farmers to make small irrigation dams, to produce local manure. It is not that. What is happening today is that the government is buying so many tractors and they are importing a lot of fertilizers, chemical fertilizers, which goes against the strategy they approved themselves. But it satisfies, very much, the people who are giving the money for the Green Revolution. This is the challenge we have. We have a lot of debate with the government in relation to this and in some places the government faces a lot of pressure from the small farmers when they bring solutions that are very much unsustainable. Of course, those same systems were used during the socialist period. Our government became (in debt) for about $15 billion U.S. dollars importing mechanization equipment into the country, and importing pesticides and chemical fertilizers, which then brought us problems, environmental problems. People remember that. We received all these wild things that never brought production and spoiled our soil. But it is accelerating and people know it. (On the other hand) in the whole of southern Africa, Mozambique is the country that uses less fertilizer. We only use .8 kgs per hectare, while others already use above 20, 22 kgs per hectare. We are very low, in terms of using fertilizer, because of historical reasons. The government is even trying to build a fertilizer company to produce organic fertilizer, not chemical fertilizer. In any case, we donít have money and those who have money they want us to buy a certain kind of product. Nic Paget-Clarke: Are those loans or gifts? Diamantino Nhampossa: Sometimes a loan. Sometimes a grant. Nic Paget-Clarke: So, they loan you the money to buy their tractors and then they ask for the money back later? Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes, thatís it. Itís a very, very big problem. And that tractor wonít bring growth and it wonít bring development but yet later we have to pay the interest, the capital, whatever. Nic Paget-Clarke: What does food sovereignty mean in Mozambique? Diamantino Nhampossa: For us, food sovereignty means the possibility of the people and farmers to produce their own food according to the local resources, local capacity, respecting their culture, the taste of food. Nic Paget-Clarke: Can you talk a bit about that part, the culture part? Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes. Thereís a lot of diversity in the country in terms of culture. It was messed up by the Portuguese because it was considered to be no culture, not culture. You had to change to become Portuguese and that brought us a lot of problems. There was a process during the socialist period of re-building the town and culture, in bringing the deep values of the culture in terms of food and so forth, ways of production. That was very important to regain hope, food production. Today, there is a lot of diversity, in terms of food, in terms of knowledge, what to produce, with a lot of mixture of the knowledge that came from others of the world, Portugal and other parts. But the culture remains different. In this country if you even go 100 kilometers you will find a more or less different situation, a different culture, a different way of doing things. And -- and this is very important -- it does not provoke separatists or a lack of unity. Those differences are interesting to show the different colors of the Mozambican society. Solidarity groups and cooperatives Nic Paget-Clarke: As far as where you are going -- you respect the traditional cultures and yet you are also talking about a culture that involves cooperatives? Is that correct? Diamantino Nhampossa: Actually, within the traditional societies, there are associations and cooperatives, so the method we are using, we are not creating new kinds of associations and cooperatives. We work on associations and cooperatives that are already there in a traditional manner. We can add to them some aspects but we donít go and say, ďLetís create an association or cooperativeĒ out of nowhere. That is a process of the local things that are already happening in the community. The communities already have solidarity groups. These are the groups that can develop into something more. Nic Paget-Clarke: What is a solidarity group? Diamantino Nhampossa: Iíll give you an example. Families of two, three people with 20 hectares. They canít work that. They organize themselves. They call all the community to work in that specific farm and they keep shifting like that. They move from family to family, cultivating the land, planting, and then move to another family. This is a kind of association to help in the management of the land for each family. Nic Paget-Clarke: Thatís new or traditional? Diamantino Nhampossa: Thatís a traditional approach. We can then add to that. Add elements of agroecology. We can add political education. Nic Paget-Clarke: What is political education? Diamantino Nhampossa: Giving them the basics of the state. Why am I a citizen? Citizenship information. Why do I need to vote? Why do I pay taxes? Why is there a government? General information about what is happening in society to make sure that he takes decisions taking into consideration what is happening around the country, in his local area. We also give this education to our farmers who raise a lot of discussions on the different problems they face. To help them understand the environment and take the right decision for their own lives. Nic Paget-Clarke: And the cooperatives created during the socialist period -- what about them? Diamantino Nhampossa: The cooperatives had a certain nature during the socialist period but you can see that the small farmers have been very much creative, introducing a lot of change. That old cooperative is operating in a different way. Letís say for example, in the past, the cooperative would go to the government to get funding and they would plant in the same field, all of them, and work on the same field. But now some cooperatives they take this farm and they divide it into families. What they do is say, ďLetís make a commercialization together. Letís make a market product and bargain in common.Ē That would be one example. Or ďLetís use the irrigation system for the benefit of all of us. How are we going to make the schedule of who gets the water first and who gets the water afterwards?Ē They organize themselves best for that specific resource or service which was supplied by the government in the past. They were just receptors of something that came from outside. Now it is the result of their own work, internally. Nic Paget-Clarke: So, in the socialist period farmers wouldnít have been permitted to do that and in the neoliberal period the government really doesnít care what they do, so theyíve come up with their own method? Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes, in the neolibeal period it is a survival strategy. Nic Paget-Clarke: Am I right in saying that in the socialist period they wouldnít have been permitted to do these creative things? Diamantino Nhampossa: Right. They would not have been permitted because everything was centrally planned. You had to do what was according to plan. If this area is for production of cotton, you canít change that. You have to organize yourself to produce cotton. Today, people can say, ďNo, I donít want to produce cotton. I want to produce chickens. Thatís what I think I ought to do.Ē But, in the past, although the government said you had to produce cotton, they did give you the money to produce cotton. Today, you have to find your own solutions. Nic Paget-Clarke: What about land reform? Thatís one thing that didnít change, right? Diamantino Nhampossa: In terms of land reform, the reason for the liberation war, struggle, was to free people and land. That was the objective and that objective was obtained. In 1975, land was free, people were free. Thatís when we had our land reform. So what happened? All the farms were nationalized. All those really big farms were taken away and then given back to their owners, as in the past, before colonialization. All the small farmers took over different farms and then that was it. Nic Paget-Clarke: As families? Diamantino Nhampossa: As families. They took their own land as families. But when the government came four years later creating cooperatives, some of those farms that belonged to the colonial period were used as cooperatives. Some of the farms, they were basically the surroundings of the cities. Nic Paget-Clarke: So, who owns the land now? Diamantino Nhampossa: Who owns the land? At that time, those cooperatives would own that piece of land which used to be the colonial farm. Under the new constitution, after independence, the land belongs to the state. And when I say the state, I am not talking about the adminstration, the government, Iím talking about the state, the people. The territory belongs to everyone. In other words, to give you an example, the government is not allowed to sell land. I have a piece of land and the government wants that land for something -- they need to consult me. If I donít agree, they donít touch my land. The government acts at the same level as a citizen when it comes to land issues, unless itís for public use, letís say for roads or anything like that. That is different. But if it is for economic activities, we are at the same level - the government and the people -- because the land belongs to the state. The state is all of us, people, government. Thatís where the difference is. Of course, some people feel afraid when they say the land belongs to the state. How can you survive like that? It is possible. People have use-rights. If you want to do economic activities, it is fifty years. And you can renew. You pay taxes but if it is for associations or cooperatives or family use, you donít pay anything. That land is yours. Thatís it. Nic Paget-Clarke: And they still have that strength or that ability? Diamantino Nhampossa: The law is still active. There was a constitutional revision in 2004 and there was a lot of expectation from the donors and the private sector that the parliament would say land should now be private property; that it should be able to be bought by private people and then sold if they want. But they did not change that clause in the constitution. In Mozambique, you cannot buy land or sell land. It is not part of the economy. Nic Paget-Clarke: So the IMF hasnít won that battle? Diamantino Nhampossa: No, they havenít. And itís not going to be an easy battle. As far as I know, the World Bank is not very much interested in touching that issue any more. It is highly political in Mozambique and no president would ever do that today because he would lose elections. They are afraid of touching this issue. Perhaps after ten years or twenty years. But today, people feel safe the way the issue is because we are watching the problems in South Africa, where land is private and the vast majority of people are without land. That is why there is so much social instability in South Africa. Crime and suffering. South Africa appears to be more developed than Mozambique, but if you visit the rural areas, the Black communities are poorer than our Black communities, our communities, because they donít have access to land, while most of our people have access to land. When there is a drop of rain that can change their life. But in South Africa they are not allowed to plant anything at all. Nic Paget-Clarke: So would you say that was one change of the socialist period that has been good that remains to this day? Diamantino Nhampossa: Yes. And the same happened in Zimbabwe. The problem that Zimbabwe is facing today is related to the fact that they did not take that decision when they became independent. They kept the land under the hands of the old colonials and when they decide to take it way it is too late. Now, there are no double powers like in the Cold War period. We managed to do that because of the backup of the Soviet Union. Today, no one dares to. If you do that you will have all kinds of sanctions and the international press. Nic Paget-Clarke: Is it true that what they are doing in Zimbabwe is they are giving land to their buddies and not to the people? Diamantino Nhampossa: It is partly true, but not true. It is true that Mugabe is corrupt. He is a dangerous man. He is a criminal. And heís been like that since the í80s. He killed minorities. And yet the British never said anything at all. I remember in the í80s, when Queen Elizabeth visited Harare, he ordered that thousands of people should be cleaned from the suburbs to make the city clean for the Queen. He also did it two years ago and it was highly criticized. The issue is not Mugabe. Mugabe, of course, is taking some of the land and giving it to a few ministers. To keep his power he needs to be able to give a lot of land to people. But on the other side, there are a lot of small farmers that have access to land now, who have not had access to land in the past, through this agrarian reform process that took place. There are two kinds of people in Zimbabwe. One is the urban elites, middle classes, and the others are the poor in the rural areas. The ones who feel in their body the problems of Zimbabwe are the middle classes in the cities. The people in the rural areas are very happy because theyíve got a piece of land now to cultivate. That makes a lot of difference. We are watching that in our neighboring countries, South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe. Itís happening and people here are thinking we wouldnít like to see these things happening in our country after a war that was supposed to liberate people and land. It is like going back. In fact, it is actually something that somebody from the World Bank told me. He said, ďI think that if you privatize your land you will be walking behind, going back. The biggest problems in the world today are related to land, and you have done the job of the land, giving out the land to small farmers. If you now decide to give billions of hectares to one man who is going to sit on top of the community, you are preparing yourselves for war in the future.Ē I donít know why he said that. I actually have his paper where he is putting some of these things forward. I think he is a South African and he knows what is happening in his own country is not a joke. The level of crime that is there is related to the fact that people donít have access to resources. Not everybody can get employment and be able to survive. Here, unemployment is high but people are self-employed on their own farms. That is very important. What we need is policies in support of this agriculture to make sure that we produce a little bit more and are able to access the market. Our production is not accessing the market at all. Our markets are occupied by South African products and our small farmers are not yet able to bring their products to market centers. This is a problem which we need to solve. But not the land issue. Nic Paget-Clarke: Is there anything else youíd like to say? Diamantino Nhampossa: There is one thing that is important to say. It is the subsidy issue. There is a misunderstanding on the issue of subsidies. We are not against subsidies. Iím talking about good subsidies, not bad subsidies. Good subsidies, I consider, are those that are given to the small farmers to produce in a sustainable manner to supply the local markets. Bad subsidies would be those that are given to multinational companies to produce and export and promote dumping in other countries. I think the issue of subsidies is very important in the WTO and the Americans are playing an important role in those issues. It is very important to make the separation between these two things. Many people are saying, ďIf you give subsidies to your farmers you are going to clash with farmers in Africa because they will never be able to export to America.Ē Our dream is not to export anything to America at all. Our dream is to be able to produce for local consumption. We also dream that Americans should be able to produce in their country to supply their market. [This interview originally appeared in In Motion Magazine.] BlackCommentator.com Guest Commentator Nic Paget-Clarke is Publisher and Co-editor of In Motion Magazine where this article originally appeared December 16, 2008. In Motion Magazine ģ is a multicultural, online U.S. publication about democracy. Click here to contact Mr. Paget-Clarke. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Any BlackCommentator.com article may be re-printed so long as it is re-printed in its entirety and full credit given to the author and www.BlackCommentator.com. If the re-print is on the Internet we additionally request a link back to the original piece on our Website. Your comments are always welcome. eMail re-print notice

If you send us an eMail message we may publish all or part of it, unless you tell us it is not for publication. You may also request that we withhold your name. Thank you very much for your readership. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| February

5, 2009 Issue 310 |

|

| Executive Editor: Bill Fletcher, Jr. |

| Managing Editor: Nancy Littlefield |

| Publisher: Peter Gamble |

| Est. April 5, 2002 |

Printer Friendly Version

in resizeable plain

text format or pdf

format. |

| Frequently Asked Questions |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |