This

article was first published in the Winter edition of ColorLines

magazine, now on newsstands.

The

historical foes of Black America are engaged in a new and multi-layered

strategy to subvert the general political consensus that has prevailed

among Blacks since the dramatic death rattles of official Jim Crow,

in the mid and late Sixties. Begun in earnest only a few years ago,

this heavily-funded, media-driven campaign seeks to undermine existing

African American political structures by creating the appearance

of deep class and age divisions within the Black body-politic.

The

historical foes of Black America are engaged in a new and multi-layered

strategy to subvert the general political consensus that has prevailed

among Blacks since the dramatic death rattles of official Jim Crow,

in the mid and late Sixties. Begun in earnest only a few years ago,

this heavily-funded, media-driven campaign seeks to undermine existing

African American political structures by creating the appearance

of deep class and age divisions within the Black body-politic.

The

Hard Right's New Black Strategy is, essentially, an enterprise of

subversion and stealth. Its immediate goal is to shatter the remarkable

degree of public unity around core issues that has evolved among

all significant demographic cohorts of African Americans. Blacks

remain the bulwark of the progressive wing of the Democratic Party,

and the only ethnic group that can be counted on to oppose

the Right agenda as a near-solid bloc.

The

Right's aim is to subvert, not convert, Black America. Ample funds

have been made available to create confusion as was evident during

the past year's electoral contests in New Jersey, Alabama, and Georgia.

Corporate interests poured $2.8 million into Cory Booker's attempt

to unseat Newark's Sharpe James, outspending the mayor by half a

million dollars. The same network, supplemented by a furious assault

from pro-Israel lobby groups, knocked out Representatives Earl Hilliard

and Cynthia McKinney. In all three races, corporate media were actively

allied with corporate cash, providing millions of dollars in free,

shamelessly partisan coverage.

Appearances

are everything in this game of images and impressions. Any and all

divisions among Blacks - real or imagined, perceptual or concrete

- are described as fundamental, and immediately exhibited as proof

of the dissolution of the Black Consensus. Two easily flattered

cohorts have been targeted by this most cynical strategy: the Black

"middle class," very loosely defined so as to encompass

all who are anxious to believe they are members; and Black youth,

also ambiguously described as the hip-hop generation.

Through

media, both groups are artificially pitted against an equally amorphous

cohort, the Civil Rights Generation(s), defenders of an "irrelevant"

and "out-dated" Civil Rights Agenda - which turns out

to be very much like the actual Black Consensus on a broad range

of unfinished political business.

The

Hard Right's New Black Strategy holds special dangers for young

African Americans, the most media-dependent generation in human

history.

Massaging

the Products

For

six and a half years, beginning in August 1986, I owned and hosted

"Rap It Up," the first nationally syndicated hip-hop music

show, broadcast on 66 commercial radio stations.

Like

any other host, my mission was to add value to my program's product

- the performers and their records - for consumption by the listening

audience. These consumers were also my product, since I gathered,

counted and sold them to the advertisers who paid the bills, mainly

record companies. That's how commercial radio and television work;

both the audiences and the performers are products, commodities

for commercial trade.

All

hosts attempt to add value to their performers and flatter their

audiences. We tell audiences how smart and hip they are, and we

interpret and embellish the utterances of performers so as to give

their words the appearance of weight, enduring meaning, intrinsic

value.

Shamelessly,

I proclaimed that each rapper's attempt at serious social commentary

was deeply profound: MC So and So is "droppin' science!"

As

the syndication moved into the 90s, I grew concerned at the deepening

strangeness of the hip-hop milieu: an excess of young entertainers

with delusions of grandeur; too many fans who seemed to think that

they were the artists; kids whose freestyle rhymes consisted mainly

of stringing one brand name after the other.

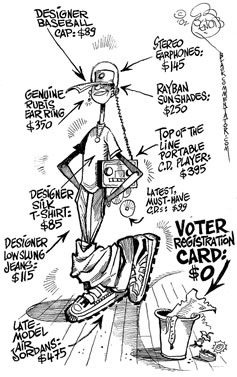

Black

America's hip-hop generation has been convinced by the social engineers

of market capitalism that they are a very special and unique demographic

- and who would disagree? Youth are, of course, precious to humanity

in every epoch. Their value is inarguable, as repositories of the

future, and as the most active elements of any society.

Oppressed

communities are particularly dependent on their young people - who

else will achieve all those murdered dreams? But, what happens when

a generation of the oppressed is disconnected from its immediate

past and left to the tender mercies of its direct enemies? This

is the prospect facing the Black hip-hop generation, many of whom

have been rendered politically impotent through an enthusiastic

embrace of their own commodification.

Oppressed

communities are particularly dependent on their young people - who

else will achieve all those murdered dreams? But, what happens when

a generation of the oppressed is disconnected from its immediate

past and left to the tender mercies of its direct enemies? This

is the prospect facing the Black hip-hop generation, many of whom

have been rendered politically impotent through an enthusiastic

embrace of their own commodification.

It

is a death-grip that threatens to fracture the community's political

coherence. Bombarded by blandishments from merchandisers, flush

with illusions of power based solely on market status, Black youth

have become vulnerable to political appeals from anyone offering

attention and flattery.

Status

vs. Power

Media

critic Mark Crispin, among a raft of experts featured in the February

2001 PBS Frontline program "The Merchants of Cool," described

today's mass marketing machinery this way: "It closely studies

the young, keeps them under very tight surveillance, to figure out

what will push their buttons. Then it takes that and blares it back

at them relentlessly and everywhere."

Todd

Cunningham, a young Black man with the title of Senior VP for Brand

Strategy andPlanning at MTV, agreed that the "current generation

[of youth] is history's 'most marketed-to.'" This is bad news

for Americans of every ethnicity, but young Blacks, on the  strength

of their world-rocking cultural inventiveness, have earned the cruelest

distinction. As the universally recognized "cutting edge"

demographic of popular American youth culture, Blacks are wooed

in qualitatively different ways than the general youth population.

White youth emulate Blacks - a marketing fact. It can be argued

that world youth emulate African Americans. Marketers ply

Black youth with messages for gear, liquors, beverages, and other

lifestyle products, in hopes of launching a general market trend.

In many product categories, far more attention is focused on the

Black youth market than is justified by the group's spending power,

which is significantly less than that of whites of similar age.

Marketers are investing in crossover effects with worldwide potential.

strength

of their world-rocking cultural inventiveness, have earned the cruelest

distinction. As the universally recognized "cutting edge"

demographic of popular American youth culture, Blacks are wooed

in qualitatively different ways than the general youth population.

White youth emulate Blacks - a marketing fact. It can be argued

that world youth emulate African Americans. Marketers ply

Black youth with messages for gear, liquors, beverages, and other

lifestyle products, in hopes of launching a general market trend.

In many product categories, far more attention is focused on the

Black youth market than is justified by the group's spending power,

which is significantly less than that of whites of similar age.

Marketers are investing in crossover effects with worldwide potential.

This

intimate courtship of Black youth involves every form of flattery

that the corporate marketing mind can devise. Like no previous age/race

cohort, a large chunk of the hip-hop generation has been made to

believe that they need do nothing to merit attention and praise;

simply being part of their age and ethnic group - the hyper-valued

demographic - is enough. Corporate marketers have relentlessly taught

them so. Thus, Black youth embrace their own commodification, basking

under the corporate marketer's loving gaze, believing themselves

to be a powerful, autonomous force.

In

truth, they possess only the power to buy, and to influence others

to buy. They have achieved a certain market status - not

power.

Enter

the Right and its network of funders, armed with their New Black

Strategy. This media-driven offensive is radically different from

the Right's previous attempts to influence African American opinion:

"[The

Right's] Black-related activities were largely limited to funding

compliant African American academics, and to subsidizing single-person

front organizations such as Ward Connerly's California operations

and Robert Woodson's Center for Neighborhood Enterprise. Attempts

to legitimize Black Republican vehicles such as the Center for New

Black Leadership proved ineffective among the Black populace at-large."

(See "Fruit

of the Poisoned Tree, April 5.)

The

Bradley Foundation, of Milwaukee, author of much of the national

Republican Party's social program, hatched a new game plan, deployed

with devastating effect in 2001- 02. Rather than continue to tinker

on the peripheries of the Black body-politic, the Right would cultivate

and bankroll nominal Democrats as stealth candidates for office.

Win or lose, the votes garnered by these mercenaries would be interpreted

as proof that the Black Consensus is crumbling.

This

year's Trojan Horse trio were Cory Booker, unsuccessful candidate

for Mayor of Newark, New Jersey, and triumphant congressional candidates

Arthur Davis, in Alabama, and Denise Majette, in Georgia. Hard Right

money made them viable challengers; the corporate media provided

the post-mortem: the Black Consensus is dead. African American politicians

and organizations no longer "represent" Black opinion.

Ignore them.

Corporate

media made a fetish of supposed Black middle class disgruntlement

in the Alabama and Georgia contests, while alienated African American

youth were trumpeted as regime-changers in Newark. Booker, a 33

year-old Harvard-trained lawyer and first-term councilman, raised

in an overwhelmingly white suburb, represented a "new generation"

that would wrench control from "civil-rights oriented"

and "machine" politicians like 66 year-old Mayor Sharpe

James.

Booker

became the national poster boy for a general Black political house

cleaning, one that would sweep away aging officeholders and "out-dated"

ideas. Reactionary columnist-prince George F. Will proclaimed that

Booker got his ideas from white conservatives, whom Will

proudly listed. No matter. Booker was declared authentic, a genuine

expression of youthful Black aspirations. Corporate media gave hardly

an inch of exposure to the candidate's well documented ties to the

Bradley Foundation's political network, the machine that enabled

Booker to vastly outspend a four term incumbent, the most influential

Black politician in the history of the state.

The

Right's young front man nearly won, without having to articulate

a single issue of substance. In the last weeks of the campaign,

he polled well among younger "likely voters" in the majority-Black

city, pulling even with Mayor James. In the real world, that meant

a 53-46 percent victory for the James camp; younger voters didn't

show up on Election Day. Sharpe James won every Black ward, including

Booker's own.

The

Right and its media allies proclaimed victory, anyway. They had

succeeded in creating the public perception of fundamental divisions

among Blacks along generational lines. They had manufactured a political

"fact." Although the media itself had cleansed the campaign

of all issues except age, their "experts" and analysts

filled in the blanks: Black youth are chafing under an older generation's

rule, they are "independent" and "pragmatic,"

and reject the "civil rights" agenda.

The

Bradley-scripted dictum became received wisdom, the gospel according

to media.

Middle

class African Americans are, on the whole, less vulnerable to corporate

propaganda. It is they who created and control the "civil rights-oriented"

organizations that shaped the battered Black Consensus. They will

not readily abandon the "major core issues" identified

by Harvard political scientist Martin Kilson: "racist practices

in housing, job markets, income/wealth patterns, educational opportunities,

health patterns, and the criminal justice system." Affirmative

action, a key element of the Black Consensus, is an essential factor

in Black middle class mobility. Trojan Horse candidate Denise Majette

rode a white wave to victory over Congresswoman Cynthia McKinney

in Dekalb County, Georgia, this summer, but she picked up less than

20 percent of the largely middle class Black vote.

However,

the hip-hop generation is not so well-grounded; critical thinking

is the corporate marketer's first victim. It should be expected

that slickly packaged, flattering lies would resonate most effectively

among the "cutting edge" component of the "most marketed-to"

generation.

Cory

Booker, whose political allegiances are antithetical to the interests

of Black youth, remains a popular figure among a number of self-styled

hip-hop generation journalists. One of these writers will serve

as my straw man.

Embracing

the Brand

Bakari

Kitwana is a former political editor of The Source magazine

and author of The Hip Hop Generation: Young Blacks and the Crisis

in African-American Culture. In an interview with Salon.com,

Kitwana was asked to explain the political differences that he believes

cleave the generations.

"Many

people in our generation, if they're working class and have a job,

are probably living with their parents. That is a dramatic difference

between this generation and the previous generation. The older generation

has not taken enough time to try to understand what's unique about

the hip-hop generation," Kitwana said.

"In

previous generations, you could have a working class, low-skilled

job without a college degree and you could still buy a house, go

on vacation, and own a new car. For our generation that is not true.

If you don't have a college degree, your job prospects are low.

You can get a minimum wage gig with no benefits and an income that

will be below the poverty level, you can join the military, or you

can get yourself a gig in the underground economy."

There

is not a single honest, socially conscious Black person who does

not know that employment security is eroding; that young people

are entering the work force at low wages; that housing costs are

becoming prohibitive; that benefits are disappearing; that the underground

economy is expanding. Note that Kitwana's list of problems plaguing

youth falls entirely within the "major issues" outlined

by Dr. Martin Kilson, the 72 year-old Harvard political scientist.

The

key phrase in Kitwana's complaint asks the listener to contemplate

"what's unique about the hip-hop generation." Over and

over again, self-identified members of this generation return to

the subject of their uniqueness, like a mantra that contains

some over-arching truth, some self-evident meaning that demands

the attention of others.

What

role would Kitwana assign the civil rights generation, as the elders

make way for this "unique" demographic cohort?

"If

you look at the '60s generation, young national political groups

like the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee and the Black

Panthers were helped in some way in terms of getting resources in

order to create those organizations. Whether it was entertainment

figures financing those groups or the older generation groups. The

Southern Christian Leadership Conference, for example, was very

effective in helping to get SNCC off the ground."

Kitwana,

author and purported intellect of his generation, insults and utterly

mangles his own people's history without a qualm. Believing he has

said something factual and profound, Kitwana demands that others

tithe his generation so that they might assume their rightful places

of leadership.

If

the Right is listening, and they certainly are, checks will soon

be in the mail. This is the kind of "alternative" Black

leadership they can live with - disconnected, self-absorbed, and

disdainful of the race and its legacies.

I

will end with an assessment from MTV's Todd Cunningham, who speaks

with great affection for the "most marketed-to" generation:

"They

understand the way brands are built. They understand the arc that

a brand goes in terms of its lifespan, of huge popularity to dying

out or regenerating itself into something else."

Kitwana

and too many of his peers see themselves as a kind of premium brand,

rising inexorably on an arc to power. The older brands are dying

out. That's all they think they need to know.