|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

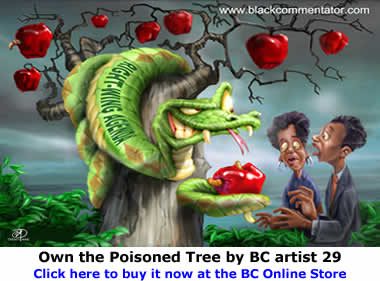

Unless the courts intervene, the public schools of Omaha, Nebraska may one day soon be divided into three ethnically distinct districts. Whites, Blacks and Hispanics would each have their own separate school districts, under a bill passed by the state legislature and signed into law by the governor. Virtually everyone, including the state attorney general, expects a huge legal battle. The courts being what they are, these days, who can say how the judges will rule. But the Omaha schools controversy provides an opportunity to remember what the long struggle for school desegregation was all about. A key argument against segregated schools was that they were inherently unequal, that they stigmatized Black students as inferior, irreparably scarring their young personalities. A more compelling argument was that enforced racial isolation allowed whites to use the myriad means at their disposal to shortchange Black schools, to make them inferior across the board, while pouring resources into schools for white children. And of course, that’s exactly what whites did, in every school district in the nation, North and South, whether segregated by law, or housing patterns, or drawing lines on a city map to make sure that Black and Latino students were kept in separate locations from whites. Whites used racial isolation to funnel resources to their own children while shortchanging Blacks.

This seems to be the school of thought to which Ernie Chambers belongs. He’s the only Black in the Nebraska state senate, and a champion of the law that would create three ethnically-based school districts in Omaha. The city’s desegregation plan was allowed to end, in 1999. Chambers says the neighborhood schools are segregated, already, because of housing patterns. That is true of elementary schools, although no Omaha high school is majority Black. Overall, Omaha’s schools are 44 percent white, 32 percent Black, and 24 percent Hispanic or Asian. If Omaha’s population – specifically, its white population – really wanted to integrate all classrooms, there are plenty of whites to go around.

His allies in the state legislature are among the most racist Republicans Nebraska has to offer. They’re as enthusiastic about separate districts as he is. No one is a more fervent believer in Black Power than I am. However, a racially isolated Black school district in the white state of Nebraska sounds to me like an educational Alamo. Those kids won’t stand a chance. For Radio BC, I’m Glen Ford. You can visit the Radio BC page to listen to any of our audio commentaries voiced by BC Co-Publisher and Executive Editor, Glen Ford. We publish the text of the radio commentary each week along with the audio program. |

|

| Home | |

Your comments are always welcome. Visit the Contact Us page to send e-Mail or Feedback or Click here to send e-Mail to [email protected] e-Mail re-print notice

If you send us an e-Mail message we may publish all or part of it, unless you tell us it is not for publication. You may also request that we withhold your name. Thank you very much for your readership. |

|

| April 20, 2006 Issue 180 |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Printer Friendly Version of article | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| |

||||||||||||||

| |

||||||||||||||