|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

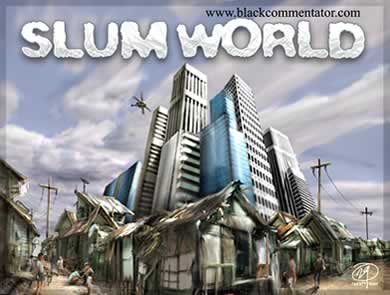

This article first appeared in New Left Review. Sometime in the next year, a woman will give birth in the Lagos slum of Ajegunle, a young man will flee his village in west Java for the bright lights of Jakarta, or a farmer will move his impoverished family into one of Lima’s innumerable pueblos jovenes. The exact event is unimportant and it will pass entirely unnoticed. Nonetheless it will constitute a watershed in human history. For the first time the urban population of the earth will outnumber the rural. Indeed, given the imprecisions of Third World censuses, this epochal transition may already have occurred. The earth has urbanized even faster than originally predicted by the Club of Rome in its notoriously Malthusian 1972 report, Limits of Growth. In 1950 there were 86 cities in the world with a population over one million; today there are 400, and by 2015, there will be at least 550. [1] Cities, indeed, have absorbed nearly two-thirds of the global population explosion since 1950 and are currently growing by a million babies and migrants each week. [2] The present urban population (3.2 billion) is larger than the total population of the world in 1960. The global countryside, meanwhile, has reached its maximum population (3.2 billion) and will begin to shrink after 2020. As a result, cities will account for all future world population growth, which is expected to peak at about 10 billion in 2050. [3]

Click to view larger and printable version of cartoon

1. THE URBAN CLIMACTERIC Where are the heroes, the colonisers, the victims of the Metropolis? – Brecht, Diary entry, 1921 Ninety-five per cent of this final buildout of humanity will occur in the urban areas of developing countries, whose population will double to nearly 4 billion over the next generation. [4] (Indeed, the combined urban population of China, India and Brazil already roughly equals that of Europe plus North America.) The most celebrated result will be the burgeoning of new megacities with populations in excess of 8 million, and, even more spectacularly, hypercities with more than 20 million inhabitants (the estimated urban population of the world at the time of the French Revolution). [5] In 1995 only Tokyo had incontestably reached that threshold. By 2025, according to the Far Eastern EconomicReview, Asia alone could have ten or eleven conurbations that large, including Jakarta (24.9 million), Dhaka (25 million) and Karachi (26.5 million). Shanghai, whose growth was frozen for decades by Maoist policies of deliberate under-urbanization, could have as many as 27 million residents in its huge estuarial metro-region. [6] Mumbai (Bombay) meanwhile is projected to attain a population of 33 million, although no one knows whether such gigantic concentrations of poverty are biologically or ecologically sustainable. [7] But

if megacities are the brightest stars in the urban firmament,

three-quarters of

the burden of population growth will be borne by faintly visible

second-tier cities and smaller urban areas: places where, as

UN researchers emphasize, “there is little or no planning to

accommodate these people or provide them with services.” [8]

In China (officially 43 per cent

Moreover, as Gregory Guldin has urged, urbanization must be conceptualized as structural transformation along, and intensified interaction between, every point of an urban–rural continuum. In his case-study of southern China, the countryside is urbanizing in situ as well as generating epochal migrations. “Villages become more like market and xiang towns, and county towns and small cities become more like large cities.” The result in China and much of Southeast Asia is a hermaphroditic landscape, a partially urbanized countryside that Guldin and others argue may be “a significant new path of human settlement and development…a form neither rural nor urban but a blending of the two wherein a dense web of transactions ties large urban cores to their surrounding regions.” [11] In Indonesia, where a similar process of rural/urban hybridization is far advanced in Jabotabek (the greater Jakarta region), researchers call these novel land-use patterns desokotas and debate whether they are transitional landscapes or a dramatic new species of urbanism. [12] Urbanists also speculate about the processes weaving together Third World cities into extraordinary new networks, corridors and hierarchies. For example, the Pearl River (Hong Kong–Guangzhou) and the Yangtze River (Shanghai) deltas, along with the Beijing–Tianjin corridor, are rapidly developing into urban-industrial megalopolises comparable to Tokyo–Osaka, the lower Rhine, or New York–Philadelphia. But this may only be the first stage in the emergence of an even larger structure: “a continuous urban corridor stretching from Japan/North Korea to West Java.” [13] Shanghai, almost certainly, will then join Tokyo, New York and London as one of the “world cities” controlling the global web of capital and information flows. The price of this new urban order will be increasing inequality within and between cities of different sizes and specializations. Guldin, for example, cites intriguing Chinese discussions over whether the ancient income-and-development chasm between city and countryside is now being replaced by an equally fundamental gap between small cities and the coastal giants. [14]

2. BACK TO DICKENS I saw innumerable hosts, foredoomed to darkness, dirt, pestilence, obscenity, misery and early death. – Dickens, ‘A December Vision’, 1850 The dynamics of Third World urbanization both recapitulate and confound the precedents of nineteenth and early twentieth-century Europe and North America. In China the greatest industrial revolution in history is the Archimedean lever shifting a population the size of Europe’s from rural villages to smog-choked sky-climbing cities. As a result, “China [will] cease to be the predominantly rural country it has been for millennia.” [15] Indeed, the great oculus of the Shanghai World Financial Centre may soon look out upon a vast urban world little imagined by Mao or, for that matter, Le Corbusier. But in most of the developing world, city growth lacks China’s powerful manufacturing-export engine as well as its vast inflow of foreign capital (currently equal to half of total foreign investment in the developing world). Urbanization elsewhere, as a result, has been radically decoupled from industrialization, even from development perse. Some would argue that this is an expression of an inexorable trend: the inherent tendency of silicon capitalism to delink the growth of production from that of employment. But in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, the Middle East and parts of Asia, urbanization-without-growth is more obviously the legacy of a global political conjuncture – the debt crisis of the late 1970s and subsequent IMF-led restructuring of Third World economies in the 1980s – than an iron law of advancing technology. Third World urbanization, moreover, continued its breakneck pace (3.8 per cent per annum from 1960–93) through the locust years of the 1980s and early 1990s in spite of falling real wages, soaring prices and skyrocketing urban unemployment. [16] This “perverse” urban boom contradicted orthodox economic models which predicted that the negative feedback of urban recession should slow or even reverse migration from the countryside. The African case was particularly paradoxical. How could cities in Côte d’Ivoire, Tanzania, Gabon and elsewhere – whose economies were contracting by 2 to 5 per cent per year – still sustain population growth of 5 to 8 per cent per annum? [17] Part of the secret, of course, was that IMF- (and now WTO-) enforced policies of agricultural deregulation and “de-peasantization” were accelerating the exodus of surplus rural labor to urban slums even as cities ceased to be job machines. Urban population growth in spite of stagnant or negative urban economic growth is the extreme face of what some researchers have labeled “over-urbanization.” [18] It is just one of the several unexpected tracks down which a neoliberal world order has shunted millennial urbanization. Classical social theory from Marx to Weber, of course, believed that the great cities of the future would follow in the industrializing footsteps of Manchester, Berlin and Chicago. Indeed, Los Angeles, São Paulo, Pusan and, today, Ciudad Juárez, Bangalore and Guangzhou, have roughly approximated this classical trajectory. But most cities of the South are more like Victorian Dublin which, as Emmet Larkin has emphasized, was unique amongst “all the slumdoms produced in the western world in the nineteenth century…[because] its slums were not a product of the industrial revolution. Dublin, in fact, suffered more from the problems of de-industrialization than industrialization between 1800 and 1850.” [19]

Likewise Kinshasa, Khartoum, Dar es Salaam, Dhaka and Lima grow prodigiously despite ruined import-substitution industries, shrunken public sectors and downwardly mobile middle classes. The global forces “pushing” people from the countryside – mechanization in Java and India, food imports in Mexico, Haiti and Kenya, civil war and drought throughout Africa, and everywhere the consolidation of small into large holdings and the competition of industrial-scale agribusiness – seem to sustain urbanization even when the “pull” of the city is drastically weakened by debt and depression. [20] At the same time, rapid urban growth in the context of structural adjustment, currency devaluation and state retrenchment has been an inevitable recipe for the mass production of slums. [21] Much of the urban world, as a result, is rushing backwards to the age of Dickens. The astonishing prevalence of slums is the chief theme of the historic and sombre report published last October by the United Nations’ Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). [22] The Challenge of the Slums (henceforth: Slums) is the first truly global audit of urban poverty. It adroitly integrates diverse urban case-studies from Abidjan to Sydney with global household data that for the first time includes China and the ex-Soviet Bloc. (The UN authors acknowledge a particular debt to Branko Milanovic, the World Bank economist who has pioneered the use of micro-surveys as a powerful lens to study growing global inequality. In one of his papers, Milanovic explains: “for the first time in human history, researchers have reasonably accurate data on the distribution of income or welfare [expenditures or consumption] amongst more than 90 per cent of the world population.”) [23]

Slums, to be sure, neglects (or saves for later UN-Habitat reports) some of the most important land-use issues arising from super-urbanization and informal settlement, including sprawl, environmental degradation, and urban hazards. It also fails to shed much light on the processes expelling labor from the countryside or to incorporate a large and rapidly growing literature on the gender dimensions of urban poverty and informal employment. But these cavils aside, Slums remains an invaluable exposé that amplifies urgent research findings with the institutional authority of the United Nations. If the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change represent an unprecedented scientific consensus on the dangers of global warming, then Slums sounds an equally authoritative warning about the global catastrophe of urban poverty. (A third report someday may explore the ominous terrain of their interaction.) [26] And, for the purposes of this review, it provides an excellent framework for reconnoitering contemporary debates on urbanization, the informal economy, human solidarity and historical agency.

3. THE URBANIZATION OF POVERTY The mountain of trash seemed to stretch very far, then gradually without perceptible demarcation or boundary it became something else. But what? A jumbled and pathless collection of structures. Cardboard cartons, plywood and rotting boards, the rusting and glassless shells of cars, had been thrown together to form habitation. – Michael Thelwell, The Harder They Come, 1980 The first published definition of “slum” reportedly occurs in Vaux’s 1812 Vocabulary of the Flash Language, where it is synonymous with “racket” or “criminal trade.” [27] By the cholera years of the 1830s and 1840s, however, the poor were living in slums rather than practicing them. A generation later, slums had been identified in America and India, and were generally recognized as an international phenomenon. The “classic slum” was a notoriously parochial and picturesquely local place, but reformers generally agreed with Charles Booth that all slums were characterized by an amalgam of dilapidated housing, overcrowding, poverty and vice. For nineteenth-century Liberals, of course, the moral dimension was decisive and the slum was first and above all envisioned as a place where a social “residuum” rots in immoral and often riotous splendor. Slums’ authors discard Victorian calumnies, but otherwise preserve the classical definition: overcrowding, poor or informal housing, inadequate access to safe water and sanitation, and insecurity of tenure. [28] This multi-dimensional definition is actually a very conservative gauge of what qualifies as a slum: many readers will be surprised by the UN’s counter-experiential finding that only 19.6 per cent of urban Mexicans live in slums. Yet, even with this restrictive definition, Slums estimates that there were at least 921 million slum-dwellers in 2001: nearly equal to the population of the world when the young Engels first ventured onto the mean streets of Manchester. Indeed, neoliberal capitalism has multiplied Dickens’s notorious slum of Tom-All-Alone in Bleak House by exponential powers. Residents of slums constitute a staggering 78.2 per cent of the urban population of the least developed countries and fully a third of the global urban population. [29] Extrapolating from the age structures of most Third World cities, at least half of the slum population is under the age of 20. [30]

The world’s highest percentages of slum-dwellers are in Ethiopia (an astonishing 99.4 per cent of the urban population), Chad (also 99.4 per cent), Afghanistan (98.5 percent) and Nepal (92 per cent). [31] The poorest urban populations, however, are probably in Maputo and Kinshasa where (according to other sources) two-thirds of residents earn less than the cost of their minimum required daily nutrition. [32] In Delhi, planners complain bitterly about “slums within slums” as squatters take over the small open spaces of the peripheral resettlement colonies into which the old urban poor were brutally removed in the mid-1970s. [33] In Cairo and Phnom Penh, recent urban arrivals squat or rent space on rooftops: creating slum cities in the air. Slum populations are often deliberately and sometimes massively undercounted. In the late 1980s, for example, Bangkok had an “official” poverty rate of only 5 per cent, yet surveys found nearly a quarter of the population (1.16 million) living in slums and squatter camps. [34] The UN, likewise, recently discovered that it was unintentionally undercounting urban poverty in Africa by large margins. Slum-dwellers in Angola, for example, are probably twice as numerous as it originally believed. Likewise it underestimated the number of poor urbanites in Liberia: not surprising, since Monrovia tripled its population in a single year (1989–90) as panic-stricken country people fled from a brutal civil war. [35] There may be more than a quarter of a million slums on earth. The five great metropolises of South Asia (Karachi, Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata and Dhaka) alone contain about 15,000 distinct slum communities with a total population of more than 20 million. An even larger slum population crowds the urbanizing littoral of West Africa, while other huge conurbations of poverty sprawl across Anatolia and the Ethiopian highlands; hug the base of the Andes and the Himalayas; explode outward from the skyscraper cores of Mexico, Jo-burg, Manila and São Paulo; and, of course, line the banks of the rivers Amazon, Niger, Congo, Nile, Tigris, Ganges, Irrawaddy and Mekong. The building blocks of this slum planet, paradoxically, are both utterly interchangeable and spontaneously unique: including the bustees of Kolkata, the chawls and zopadpattis of Mumbai, the katchi abadis of Karachi, the kampungs of Jakarta, the iskwaters of Manila, the shammasas of Khartoum, the umjondolos of Durban, the intra-murios of Rabat, the bidonvilles of Abidjan, the baladis of Cairo, the gecekondus of Ankara, the conventillos of Quito, the favelas of Brazil, the villas miseria of Buenos Aires and the colonias populares of Mexico City. They are the gritty antipodes to the generic fantasy-scapes and residential themeparks – Philip K. Dick’s bourgeois “Offworlds” – in which the global middle classes increasingly prefer to cloister themselves.

Whereas the classic slum was a decaying inner city, the new slums are more typically located on the edge of urban spatial explosions. The horizontal growth of cities like Mexico, Lagos or Jakarta, of course, has been extraordinary, and “slum sprawl” is as much of a problem in the developing world as suburban sprawl in the rich countries. The developed area of Lagos, for instance, doubled in a single decade, between 1985 and 1994. [36] The Governor of Lagos State told reporters last year that “about two thirds of the state’s total land mass of 3,577 square kilometres could be classified as shanties or slums.” [37] Indeed, writes a UN correspondent,

Lagos, moreover, is simply the biggest node in the shantytown corridor of 70 million people that stretches from Abidjan to Ibadan: probably the biggest continuous footprint of urban poverty on earth. [39] Slum ecology, of course, revolves around the supply of settlement space. Winter King, in a recent study published in the Harvard Law Review, claims that 85 per cent of the urban residents of the developing world “occupy property illegally.” [40] Indeterminacy of land titles and/or lax state ownership, in the last instance, are the cracks through which a vast humanity has poured into the cities. The modes of slum settlement vary across a huge spectrum, from highly disciplined land invasions in Mexico City and Lima to intricately organized (but often illegal) rental markets on the outskirts of Beijing, Karachi and Nairobi. Even in cities like Karachi, where the urban periphery is formally owned by the government, “vast profits from land speculation…continue to accrue to the private sector at the expense of low-income households.” [41] Indeed national and local political machines usually acquiesce in informal settlement (and illegal private speculation) as long as they can control the political complexion of the slums and extract a regular flow of bribes or rents. Without formal land titles or home ownership, slum-dwellers are forced into quasi-feudal dependencies upon local officials and party big shots. Disloyalty can mean eviction or even the razing of an entire district.

The provision of lifeline infrastructures, meanwhile, lags far behind the pace of urbanization, and peri-urban slum areas often have no formal utilities or sanitation provision whatsoever. [42] Poor areas of Latin American cities in general have better utilities than South Asia which, in turn, usually have minimum urban services, like water and electricity, that many African slums lack. As in early Victorian London, the contamination of water by human and animal waste remains the cause of the chronic diarrhoeal diseases that kill at least two million urban babies and small children each year. [43] An estimated 57 per cent of urban Africans lack access to basic sanitation and in cities like Nairobi the poor must rely on “flying toilets” (defecation into a plastic bag). [44] In Mumbai, meanwhile, the sanitation problem is defined by ratios of one toilet seat per 500 inhabitants in the poorer districts. Only 11 per cent of poor neighborhoods in Manila and 18 per cent in Dhaka have formal means to dispose of sewage. [45] Quite apart from the incidence of the HIV/AIDS plague, the un considers that two out of five African slum-dwellers live in a poverty that is literally “life-threatening.” [46] The urban poor, meanwhile, are everywhere forced to settle on hazardous and otherwise unbuildable terrains – over-steep hillslopes, river banks and floodplains. Likewise they squat in the deadly shadows of refineries, chemical factories, toxic dumps, or in the margins of railroads and highways. Poverty, as a result, has “constructed” an urban disaster problem of unprecedented frequency and scope, as typified by chronic flooding in Manila, Dhaka and Rio, pipeline conflagrations in Mexico City and Cubatão (Brazil), the Bhopal catastrophe in India, a munitions plant explosion in Lagos, and deadly mudslides in Caracas, La Paz and Tegucigalpa. [47] The disenfranchised communities of the urban poor, in addition, are vulnerable to sudden outbursts of state violence like the infamous 1990 bulldozing of the Maroko beach slum in Lagos (“an eyesore for the neighboring community of Victoria Island, a fortress for the rich”) or the 1995 demolition in freezing weather of the huge squatter town of Zhejiangcun on the edge of Beijing. [48] But slums, however deadly and insecure, have a brilliant future. The countryside will for a short period still contain the majority of the world’s poor, but that doubtful title will pass to urban slums by 2035. [49] At least half of the coming Third World urban population explosion will be credited to the account of informal communities. Two billion slum dwellers by 2030 or 2040 is a monstrous, almost incomprehensible prospect, but urban poverty overlaps and exceeds the slums perse. Indeed, Slums underlines that in some cities the majority of the poor actually live outside the slum strictosensu. [50] UN “Urban Observatory” researchers warn, moreover, that by 2020 “urban poverty in the world could reach 45 to 50 per cent of the total population living in cities.” [51] 4. URBAN POVERTY’S ‘BIG BANG’ After their mysterious laughter, they quickly changed the topic to other things. How were people back home surviving SAP? – Fidelis Balogun, Adjusted Lives, 1995

The evolution of the new urban poverty has been a non-linear historical process. The slow accretion of shantytowns to the shell of the city is punctuated by storms of poverty and sudden explosions of slum-building. In his collection of stories, Adjusted Lives, the Nigerian writer Fidelis Balogun describes the coming of the IMF-mandated Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) in the mid-1980s as the equivalent of a great natural catastrophe, destroying forever the old soul of Lagos and “re-enslaving” urban Nigerians.

Balogun’s complaint about “privatizing in full steam and getting more hungry by the day,” or his enumeration of SAP’s malevolent consequences, would be instantly familiar to survivors, not only of the other 30 African saps, but also to hundreds of millions of Asians and Latin Americans. The 1980s, when the IMF and World Bank used the leverage of debt to restructure the economies of most of the Third World, are the years when slums became an implacable future, not just for poor rural migrants, but also for millions of traditional urbanites, displaced or immiserated by the violence of “adjustment.” As Slums emphasizes, SAPs were “deliberately anti-urban in nature” and designed to reverse any “urban bias” that previously existed in welfare policies, fiscal structure or government investment. [53] Everywhere the IMF – acting as bailiff for the big banks and backed by the Reagan and Bush administrations – offered poor countries the same poisoned chalice of devaluation, privatization, removal of import controls and food subsidies, enforced cost-recovery in health and education, and ruthless downsizing of the public sector. (An infamous 1985 telegram from Treasury Secretary George Shultz to overseas USAID officials commanded: “in most cases, public sector firms should be privatized.”) [54] At the same time, SAPs devastated rural smallholders by eliminating subsidies and pushing them out, “sink or swim,” into global commodity markets dominated by First World agribusiness. [55]

As Ha-Joon Chang points out, SAPs hypocritically “kicked away the ladder” (i.e., protectionist tariffs and subsidies) that the OECD nations historically employed in their own climb from agriculture to urban high-value goods and services. [56] Slums makes the same point when it argues that the “main single cause of increases in poverty and inequality during the 1980s and 1990s was the retreat of the state.” In addition to the direct SAP-enforced reductions in public-sector spending and ownership, the un authors stress the more subtle diminution of state capacity that has resulted from “subsidiarity”: the devolution of powers to lower echelons of government and, especially, NGOs, linked directly to major international aid agencies.

Urban Africa and Latin America were the hardest hit by the artificial depression engineered by the IMF and the White House. Indeed, in many countries, the economic impact of SAPs during the 1980s, in tandem with protracted drought, rising oil prices, soaring interest rates and falling commodity prices, was more severe and long-lasting than the Great Depression. The balance-sheet of structural adjustment in Africa, reviewed by Carole Rakodi, includes capital flight, collapse of manufactures, marginal or negative increase in export incomes, drastic cutbacks in urban public services, soaring prices and a steep decline in real wages. [58] In Kinshasa (“an aberration or rather a sign of things to come?”) assainissement wiped out the civil servant middle class and produced an “unbelieveable decline in real wages” that, in turn, sponsored a nightmarish rise in crime and predatory gangs. [59] In Dar es Salaam, public service expenditure per person fell 10 per cent per year during the 1980s: a virtual demolition of the local state. [60] In Khartoum, liberalization and structural adjustment, according to local researchers, manufactured 1.1 million “new poor”: “mostly drawn from the salaried groups or public sector employees.” [61] In Abidjan, one of the few tropical African cities with an important manufacturing sector and modern urban services, submission to the SAP regime punctually led to deindustrialization, the collapse of construction, and a rapid deterioration in public transit and sanitation. [62] In Balogun’s Nigeria extreme poverty, increasingly urbanized in Lagos, Ibadan and other cities, metastatized from 28 per cent in 1980 to 66 per cent in 1996. “GNP per capita, at about $260 today,’ the World Bank reports, ‘is below the level at independence 40 years ago and below the $370 level attained in 1985.” [63] In Latin America, SAPs (often implemented by military dictatorships) destabilized rural economies while savaging urban employment and housing. In 1970, Guevarist “foco” theories of rural insurgency still conformed to a continental reality where the poverty of the countryside (75 million poor) overshadowed that of the cities (44 million poor). By the end of the 1980s, however, the vast majority of the poor (115 million in 1990) were living in urban colonias and villas miseria rather than farms or villages (80 million). [64] Urban inequality, meanwhile, exploded. In Santiago, the Pinochet dictatorship bulldozed shanty towns and evicted formerly radical squatters, forcing poor families to become allegados, doubled or even tripled-up in the same rented dwelling. In Buenos Aires, the richest decile’s share of income increased from 10 times that of the poorest in 1984 to 23 times in 1989. [65] In Lima, where the value of the minimum wage fell by 83 per cent during the IMF recession, the percentage of households living below the poverty threshold increased from 17 percent in 1985 to 44 percent in 1990. [66] In Rio de Janeiro, inequality as measured in classical Gini coefficients soared from 0.58 in 1981 to 0.67 in 1989. [67] Indeed, throughout Latin America, the 1980s deepened the canyons and elevated the peaks of the world’s most extreme social topography. (According to a 2003 World Bank report, Gini coefficients are 10 points higher in Latin America than Asia; 17.5 points higher than the OECD, and 20.4 points higher than Eastern Europe.) [68] Throughout the Third World, the economic shocks of the 1980s forced individuals to regroup around the pooled resources of households and, especially, the survival skills and desperate ingenuity of women. In China and the industrializing cities of Southeast Asia, millions of young women indentured themselves to assembly lines and factory squalor. In Africa and most of Latin America (Mexico’s northern border cities excepted), this option did not exist. Instead, deindustrialization and the decimation of male formal-sector jobs compelled women to improvise new livelihoods as piece workers, liquor sellers, street vendors, cleaners, washers, ragpickers, nannies and prostitutes. In Latin America, where urban women’s labor-force participation had always been lower than in other continents, the surge of women into tertiary informal activities during the 1980s was especially dramatic. [69] In Africa, where the icons of the informal sector are women running shebeens or hawking produce, Christian Rogerson reminds us that most informal women are not actually self-employed or economically independent, but work for someone else. [70] (These ubiquitous and vicious networks of micro-exploitation, of the poor exploiting the very poor, are usually glossed over in accounts of the informal sector.) Urban poverty was also massively feminized in the ex-Comecon countries after capitalist “liberation” in 1989. In the early 1990s extreme poverty in the former “transitional countries” (as the UN calls them) soared from 14 million to 168 million: a mass pauperization almost without precedent in history. [71] If, on a global balance-sheet, this economic catastrophe was partially offset by the much-praised success of China in raising incomes in its coastal cities, China’s market “miracle” was purchased by “an enormous increase in wage inequality among urban workers…during the period 1988 to 1999.” Women and minorities were especially disadvantaged. [72]

In theory, of course, the 1990s should have righted the wrongs of the 1980s and allowed Third World cities to regain lost ground and bridge the chasms of inequality created by SAPs. The pain of adjustment should have been followed by the analgesic of globalization. Indeed the 1990s, as Slums wryly notes, were the first decade in which global urban development took place within almost utopian parameters of neo-classical market freedom.

In the event, however, urban poverty continued its relentless accumulation and “the gap between poor and rich countries increased, just as it had done for the previous 20 years and, in most countries, income inequality increased or, at best, stabilized.” Global inequality, as measured by World Bank economists, reached an incredible Gini coefficient level of 0.67 by the end of the century. This was mathematically equivalent to a situation where the poorest two-thirds of the world receive zero income; and the top third, everything. [74] 5. A SURPLUS HUMANITY? We

shove our way about next to City, holding on to it by its

thousand survival

cracks… –

The brutal tectonics of neoliberal globalization since 1978 are analogous to the catastrophic processes that shaped a “third world” in the first place, during the era of late Victorian imperialism (1870–1900). In the latter case, the forcible incorporation into the world market of the great subsistence peasantries of Asia and Africa entailed the famine deaths of millions and the uprooting of tens of millions more from traditional tenures. The end result, in Latin America as well, was rural “semi-proletarianization”: the creation of a huge global class of immiserated semi-peasants and farm laborers lacking existential security of subsistence. [75] (As a result, the twentieth century became an age, not of urban revolutions as classical Marxism had imagined, but of epochal rural uprisings and peasant-based wars of national liberation.) Structural adjustment, it would appear, has recently worked an equally fundamental reshaping of human futures. As the authors of Slums conclude: “instead of being a focus for growth and prosperity, the cities have become a dumping ground for a surplus population working in unskilled, unprotected and low-wage informal service industries and trade.” “The rise of [this] informal sector,” they declare bluntly, “is…a direct result of liberalization.” [76] Indeed, the global informal working class (overlapping but non-identical with the slum population) is almost one billion strong: making it the fastest growing, and most unprecedented, social class on earth. Since anthropologist Keith Hart, working in Accra, first broached the concept of an “informal sector” in 1973, a huge literature (mostly failing to distinguish micro-accumulation from sub-subsistence) has wrestled with the formidable theoretical and empirical problems involved in studying the survival strategies of the urban poor. [77] There is a base consensus, however, that the 1980s’ crisis inverted the relative structural positions of the formal and informal sectors, promoting informal survivalism as the new primary mode of livelihood in a majority of Third World cities. Alejandro Portes and Kelly Hoffman have recently evaluated the overall impact of SAPs and liberalization upon Latin American urban class structures since the 1970s. Congruent with UN conclusions, they find that both state employees and the formal proletariat have declined in every country of the region since the 1970s. In contrast, the informal sector of the economy, along with general social inequality, has dramatically expanded. Unlike some researchers, they make a crucial distinction between an informal petty bourgeoisie (“the sum of owners of microenterprises, employing less than five workers, plus own-account professionals and technicians”) and the informal proletariat (“the sum of own-account workers minus professionals and technicians, domestic servants, and paid and unpaid workers in microenterprises”). They demonstrate that this former stratum, the microentrepreneurs” so beloved in North American business schools, are often displaced public-sector professionals or laid-off skilled workers. Since the 1980s, they have grown from about 5 to 10 per cent of the economically active urban population: a trend reflecting “the forced entrepreneurialism foisted on former salaried employees by the decline of formal sector employment.” [78]

Overall, according to Slums, informal workers are about two-fifths of the economically active population of the developing world. [79] According to researchers at the Inter-American Development Bank, the informal economy currently employs 57 per cent of the Latin American workforce and supplies four out of five new “jobs.” [80] Other sources claim that more than half of urban Indonesians and 65 per cent of residents of Dhaka subsist in the informal sector. [81] Slums likewise cites research finding that informal economic activity accounts for 33 to 40 per cent of urban employment in Asia, 60 to 75 per cent in Central America and 60 per cent in Africa. [82] Indeed, in sub-Saharan cities “formal job” creation has virtually ceased to exist. An ILO study of Zimbabwe’s urban labor markets under “stagflationary” structural adjustment in the early 1990s found that the formal sector was creating only 10,000 jobs per year in face of an urban workforce increasing by more than 300,000 per annum. [83] Slums similarly estimates that fully 90 per cent of urban Africa’s new jobs over the next decade will somehow come from the informal sector. [84] The pundits of bootstrap capitalism, like the irrepressible Hernando de Soto, may see this enormous population of marginalized laborers, redundant civil servants and ex-peasants as actually a frenzied beehive of ambitious entrepreneurs yearning for formal property rights and unregulated competitive space, but it makes more obvious sense to consider most informal workers as the “active” unemployed, who have no choice but to subsist by some means or starve. [85] The world’s estimated 100 million street kids are not likely – apologies to Señor de Soto – to start issuing IPOs or selling chewing-gum futures. [86] Nor will most of China’s 70 million “floating workers,” living furtively on the urban periphery, eventually capitalize themselves as small subcontractors or integrate into the formal urban working class. And the informal working class – everywhere subject to micro- and macro-exploitation – is almost universally deprived of protection by labor laws and standards.

Moreover, as Alain Dubresson argues in the case of Abidjan, “the dynamism of crafts and small-scale trade depends largely on demand from the wage sector.” He warns against the “illusion” cultivated by the ILO and World Bank that “the informal sector can efficiently replace the formal sector and promote an accumulation process sufficient for a city with more than 2.5 million inhabitants.” [87] His warning is echoed by Christian Rogerson who, distinguishing (à la Portes and Hoffman) “survivalist” from “growth” micro-enterprises, writes of the former: “generally speaking, the incomes generated from these enterprises, the majority of which tend to be run by women, usually fall short of even a minimum living standard and involve little capital investment, virtually no skills training, and only constrained opportunities for expansion into a viable business.” With even formal-sector urban wages in Africa so low that economists can’t figure out how workers survive (the so-called “wage puzzle”), the informal tertiary sector has become an arena of extreme Darwinian competition amongst the poor. Rogerson cites the examples of Zimbabwe and South Africa where female-controlled informal niches like shebeens and spazas are now drastically overcrowded and plagued by collapsing profitability. [88] The real macroeconomic trend of informal labor, in other words, is the reproduction of absolute poverty. But if the informal proletariat is not the pettiest of petty bourgeoisies, neither is it a “labor reserve army” or a “lumpen proletariat” in any obsolete nineteenth-century sense. Part of it, to be sure, is a stealth workforce for the formal economy and numerous studies have exposed how the subcontracting networks of Wal-Mart and other mega-companies extend deep into the misery of the colonias and chawls. But at the end of the day, a majority of urban slum-dwellers are truly and radically homeless in the contemporary international economy. Slums, of course, originate in the global countryside where, as Deborah Bryceson reminds us, unequal competition with large-scale agro-industry is tearing traditional rural society “apart at the seams.” [89] As rural areas lose their “storage capacity,” slums take their place, and urban “involution” replaces rural involution as a sink for surplus labor which can only keep pace with subsistence by ever more heroic feats of self-exploitation and the further competitive subdivision of already densely filled survival niches. [90] “Modernization,” “Development” and, now, the unfettered “Market” have had their day. The labor-power of a billion people has been expelled from the world system, and who can imagine any plausible scenario, under neoliberal auspices, that would reintegrate them as productive workers or mass consumers? 6. MARX AND THE HOLY GHOST [The Lord says:] The time will come when the poor man will say that he has nothing to eat and work will be shut down…. That is going to cause the poor man to go to these places and break in to get food. This will cause the rich man to come out with his gun to make war with the laboring man…blood will be in the streets like an outpouring rain from heaven. – A prophecy from the 1906 ‘Azusa Street Awakening’ The late capitalist triage of humanity, then, has already taken place. The global growth of a vast informal proletariat, moreover, is a wholly original structural development unforeseen by either classical Marxism or modernization pundits. Slums indeed challenges social theory to grasp the novelty of a true global residuum lacking the strategic economic power of socialized labor, but massively concentrated in a shanty-town world encircling the fortified enclaves of the urban rich.

Tendencies toward urban involution, of course, existed during the nineteenth century. The European industrial revolutions were incapable of absorbing the entire supply of displaced rural labor, especially after continental agriculture was exposed to the devastating competition of the North American prairies from the 1870s. But mass immigration to the settler societies of the Americas and Oceania, as well as Siberia, provided a dynamic safety-valve that prevented the rise of mega-Dublins as well as the spread of the kind of underclass anarchism that had taken root in the most immiserated parts of Southern Europe. Today surplus labor, by contrast, faces unprecedented barriers – a literal “great wall” of high-tech border enforcement – blocking large-scale migration to the rich countries. Likewise, controversial population resettlement programs in “frontier” regions like Amazonia, Tibet, Kalimantan and Irian Jaya produce environmental devastation and ethnic conflict without substantially reducing urban poverty in Brazil, China and Indonesia. Thus only the slum remains as a fully franchised solution to the problem of warehousing the twenty-first century’s surplus humanity. But aren’t the great slums, as a terrified Victorian bourgeoisie once imagined, volcanoes waiting to erupt? Or does ruthless Darwinian competition, as increasing numbers of poor people compete for the same informal scraps, ensure self-consuming communal violence as yet the highest form of urban involution? To what extent does an informal proletariat possess that most potent of Marxist talismans: “historical agency”? Can disincorporated labor be reincorporated in a global emancipatory project? Or is the sociology of protest in the immiserated megacity a regression to the pre-industrial urban mob, episodically explosive during consumption crises, but otherwise easily managed by clientelism, populist spectacle and appeals to ethnic unity? Or is some new, unexpected historical subject, à la Hardt and Negri, slouching toward the supercity? In truth, the current literature on poverty and urban protest offers few answers to such large-scale questions. Some researchers, for example, would question whether the ethnically diverse slum poor or economically heterogeneous informal workers even constitute a meaningful “class in itself,” much less a potentially activist “class for itself.” Surely, the informal proletariat bears “radical chains” in the Marxist sense of having little or no vested interest in the preservation of the existing mode of production. But because uprooted rural migrants and informal workers have been largely dispossessed of fungible labor-power, or reduced to domestic service in the houses of the rich, they have little access to the culture of collective labor or large-scale class struggle. Their social stage, necessarily, must be the slum street or marketplace, not the factory or international assembly line. Struggles of informal workers, as John Walton emphasizes in a recent review of research on social movements in poor cities, have tended, above all, to be episodic and discontinuous. They are also usually focused on immediate consumption issues: land invasions in search of affordable housing and riots against rising food or utility prices. In the past, at least, “urban problems in developing societies have been more typically mediated by patron–client relations than by popular activism.” [91] Since the debt crisis of the 1980s, neopopulist leaders in Latin America have had dramatic success in exploiting the desperate desire of the urban poor for more stable, predictable structures of daily life. Although Walton doesn’t make the point explicitly, the urban informal sector has been ideologically promiscuous in its endorsement of populist saviors: in Peru rallying to Fujimori, but in Venezuela embracing Chávez. [92] In Africa and South Asia, on the other hand, urban clientelism too often equates with the dominance of ethno-religious bigots and their nightmare ambitions of ethnic cleansing. Notorious examples include the anti-Muslim militias of the Oodua People’s Congress in Lagos and the semi-fascist Shiv Sena movement in Bombay. [93] Will such “eighteenth-century” sociologies of protest persist into the middle twenty-first century? The past is probably a poor guide to the future. History is not uniformitarian. The new urban world is evolving with extraordinary speed and often in unpredictable directions. Everywhere the continuous accumulation of poverty undermines existential security and poses even more extraordinary challenges to the economic ingenuity of the poor. Perhaps there is a tipping point at which the pollution, congestion, greed and violence of everyday urban life finally overwhelm the ad hoc civilities and survival networks of the slum. Certainly in the old rural world there were thresholds, often calibrated by famine, that passed directly to social eruption. But no one yet knows the social temperature at which the new cities of poverty spontaneously combust. Indeed, for the moment at least, Marx has yielded the historical stage to Mohammed and the Holy Ghost. If God died in the cities of the industrial revolution, he has risen again in the postindustrial cities of the developing world. The contrast between the cultures of urban poverty in the two eras is extraordinary. As Hugh McLeod has shown in his magisterial study of Victorian working-class religion, Marx and Engels were largely accurate in their belief that urbanization was secularizing the working class. Although Glasgow and New York were partial exceptions, “the line of interpretation that associates working-class detachment from the church with growing class consciousness is in a sense incontestable.” If small churches and dissenting sects thrived in the slums, the great current was active or passive disbelief. Already by the 1880s, Berlin was scandalizing foreigners as “the most irreligious city in the world” and in London, median adult church attendance in the proletarian East End and Docklands by 1902 was barely 12 per cent (and that mostly Catholic). [94] In Barcelona, of course, an anarchist working class sacked the churches during the Semana Trágica, while in the slums of St. Petersburg, Buenos Aires and even Tokyo, militant workers avidly embraced the new faiths of Darwin, Kropotkin and Marx.

Today, on the other hand, populist Islam and Pentecostal Christianity (and in Bombay, the cult of Shivaji) occupy a social space analogous to that of early twentieth-century socialism and anarchism. In Morocco, for instance, where half a million rural emigrants are absorbed into the teeming cities every year, and where half the population is under 25, Islamicist movements like “Justice and Welfare,” founded by Sheik Abdessalam Yassin, have become the real governments of the slums: organizing night schools, providing legal aid to victims of state abuse, buying medicine for the sick, subsidizing pilgrimages and paying for funerals. As Prime Minister Abderrahmane Youssoufi, the Socialist leader who was once exiled by the monarchy, recently admitted to Ignacio Ramonet, “We [the Left] have become embourgeoisified. We have cut ourselves off from the people. We need to reconquer the popular quarters. The Islamicists have seduced our natural electorate. They promise them heaven on earth.” An Islamicist leader, on the other hand, told Ramonet: “confronted with the neglect of the state, and faced with the brutality of daily life, people discover, thanks to US, solidarity, self-help, fraternity. They understand that Islam is humanism.” [95] The counterpart of populist Islam in the slums of Latin America and much of sub-Saharan Africa is Pentecostalism. Christianity, of course, is now, in its majority, a non-Western religion (two-thirds of its adherents live outside Europe and North America), and Pentecostalism is its most dynamic missionary in cities of poverty. Indeed the historical specificity of Pentecostalism is that it is the first major world religion to have grown up almost entirely in the soil of the modern urban slum. With roots in early ecstatic Methodism and African-American spirituality, Pentecostalism “awoke” when the Holy Ghost gave the gift of tongues to participants in an interracial prayer marathon in a poor neighborhood of Los Angeles (Azfa Street) in 1906. Unified around spirit baptism, miracle healing, charismata and a premillennial belief in a coming world war of capital and labor, early American Pentecostalism – as religious historians have repeatedly noted – originated as a “prophetic democracy” whose rural and urban constituencies overlapped, respectively, with those of Populism and the IWW. [96] Indeed, like Wobbly organizers, its early missionaries to Latin America and Africa “lived often in extreme poverty, going out with little or no money, seldom knowing where they would spend the night, or how they would get their next meal.” [97] They also yielded nothing to the IWW in their vehement denunciations of the injustices of industrial capitalism and its inevitable destruction. Symptomatically, the first Brazilian congregation, in an anarchist working-class district of São Paulo, was founded by an Italian artisan immigrant who had exchanged Malatesta for the Spirit in Chicago. [98] In South Africa and Rhodesia, Pentecostalism established its early footholds in the mining compounds and shantytowns; where, according to Jean Comaroff, “it seemed to accord with indigenous notions of pragmatic spirit forces and to redress the depersonalization and powerlessness of the urban labor experience.” [99] Conceding a larger role to women than other Christian churches and immensely supportive of abstinence and frugality, Pentecostalism – as R. Andrew Chesnut discovered in the baixadas of Belém – has always had a particular attraction to “the most immiserated stratum of the impoverished classes”: abandoned wives, widows and single mothers. [100] Since 1970, and largely because of its appeal to slum women and its reputation for being color-blind, it has been growing into what is arguably the largest self-organized movement of urban poor people on the planet. [101] Although recent claims of “over 533 million Pentecostal/charismatics in the world in 2002” are probably hyperbole, there may well be half that number. It is generally agreed that 10 per cent of Latin America is Pentecostal (about 40 million people) and that the movement has been the single most important cultural response to explosive and traumatic urbanization. [102] As Pentecostalism has globalized, of course, it has differentiated into distinct currents and sociologies. But if in Liberia, Mozambique and Guatemala, American-sponsored churches have been vectors of dictatorship and repression, and if some us congregations are now gentrified into the suburban mainstream of fundamentalism, the missionary tide of Pentecostalism in the Third World remains closer to the original millenarian spirit of Azusa Street. [103] Above all, as Chesnut found in Brazil, “Pentecostalism…remains a religion of the informal periphery” (and in Belém, in particular, “the poorest of the poor”). In Peru, where Pentecostalism is growing almost exponentially in the vast barriadas of Lima, Jefrey Gamarra contends that the growth of the sects and of the informal economy “are a consequence of and a response to each other.” [104] Paul Freston adds that it “is the first autonomous mass religion in Latin America…. Leaders may not be democratic, but they come from the same social class.” [105] In contrast to populist Islam, which emphasizes civilizational continuity and the trans-class solidarity of faith, Pentecostalism, in the tradition of its African-American origins, retains a fundamentally exilic identity. Although, like Islam in the slums, it efficiently correlates itself to the survival needs of the informal working class (organizing self-help networks for poor women; offering faith healing as para-medicine; providing recovery from alcoholism and addiction; insulating children from the temptations of the street; and so on), its ultimate premise is that the urban world is corrupt, injust and unreformable. Whether, as Jean Comaroff has argued in her book on African Zionist churches (many of which are now Pentecostal), this religion of “the marginalized in the shantytowns of neocolonial modernity” is actually a “more radical” resistance than “participation in formal politics or labour unions,” remains to be seen. [106] But, with the Left still largely missing from the slum, the eschatology of Pentecostalism admirably refuses the inhuman destiny of the Third World city that Slums warns about. It also sanctifies those who, in every structural and existential sense, truly live in exile. [1] UN Population Division, World Urbanization Prospects, the 2001 Revision, New York 2002. [2] Population Information Program, Population Reports: Meeting the Urban Challenge, vol. xxx, no. 4, Fall 2002, p. 1. [3] Wolfgang Lutz, Warren Sandeson and Sergei Scherbov, ‘Doubling of world population unlikely’, Nature 387, 19 June 1997, pp. 803–4. However the populations of sub-Saharan Africa will triple and India, double. [4] Global Urban Observatory, Slums of the World: The face of urban poverty in the new millennium?, New York 2003, p. 10. [5] Although the velocity of global urbanization is not in doubt, the growth rates of specific cities may brake abruptly as they encounter the frictions of size and congestion. A famous instance of such a ‘polarization reversal’ is Mexico City: widely predicted to achieve a population of 25 million during the 1990s (the current population is probably about 18 or 19 million). See Yue-man Yeung, ‘Geography in an age of mega-cities’, International Social Sciences Journal 151, 1997, p. 93. [6] For a perspective, see Yue-Man Yeung, ‘Viewpoint: Integration of the Pearl River Delta’, International Development Planning Review, vol. 25, no. 3, 2003. [7] Far Eastern Economic Review, Asia 1998 Yearbook, p. 63. [8] UN-Habitat, The Challenge of the Slums: Global Report on Human Settlements 2003, London 2003, p. 3. [9] Gregory Guldin, What’s a Peasant to Do? Village Becoming Town in Southern China, Boulder, co 2001, p. 13. [10] Miguel Villa and Jorge Rodriguez, ‘Demographic trends in Latin America’s metropolises, 1950–1990’, in Alan Gilbert, ed., The Mega-City in Latin America, Tokyo 1996, pp. 33–4. [11] Guldin, Peasant, pp. 14, 17. See also Jing Neng Li, ‘Structural and Spatial Economic changes and their Effects on Recent Urbanization in China’, in Gavin Jones and Pravin Visaria, eds, Urbanization in Large Developing Countries, Oxford 1997, p. 44. [12] See T. McGee, ‘The Emergence of Desakota Regions in Asia: Expanding a Hypothesis’, in Northon Ginsburg, Bruce Koppell and T. McGee, eds, The Extended Metropolis: Settlement Transition in Asia, Honolulu 1991. [13] Yue-man Yeung and Fu-chen Lo, ‘Global restructuring and emerging urban corridors in Pacific Asia’, in Lo and Yeung, eds, Emerging World Cities in Pacific Asia, Tokyo 1996, p. 41. [14] Guldin, Peasant, p. 13. [15] Wang Mengkui, advisor to the State Council, quoted in the Financial Times, 26 November 2003. Since the market reforms of the late 1970s it is estimated that almost 300 million Chinese have moved from rural areas to cities. Another 250 or 300 million are expected to follow in coming decades. (Financial Times, 16 December 2003.) [16] Josef Gugler, ‘Introduction—II. Rural–Urban Migration’, in Gugler, ed., Cities in the Developing World: Issues, Theory and Policy, Oxford 1997, p. 43. For a contrarian view that disputes generally accepted World Bank and UN data on continuing high rates of urbanization during the 1980s, see Deborah Potts, ‘Urban lives: Adopting new strategies and adapting rural links’, in Carole Rakodi, ed., TheUrban Challenge in Africa: Growth and Management of Its Large Cities, Tokyo 1997, pp. 463–73. [17] David Simon, ‘Urbanization, globalization and economic crisis in Africa’, in Rakodi, Urban Challenge, p. 95. [18] See Josef Gugler, ‘Overurbanization Reconsidered’, in Gugler, Cities in the Developing World, pp. 114–23. By contrast, the former command economies of the Soviet Union and Maoist China restricted in-migration to cities and thus tended toward ‘under-urbanization’. [19] Foreword to Jacinta Prunty, Dublin Slums 1800–1925: A Study in Urban Geography, Dublin 1998, p. ix. [20] ‘Thus, it appears that for low income countries, a significant fall in urban incomes may not necessarily produce in the short term a decline in rural–urban migration.’ Nigel Harris, ‘Urbanization, Economic Development and Policy in Developing Countries’, Habitat International, vol. 14, no. 4, 1990, p. 21–2. [21] On Third World urbanization and the global debt crisis, see York Bradshaw and Rita Noonan, ‘Urbanization, Economic Growth, and Women’s Labour-Force Participation’, in Gugler, Cities in the DevelopingWorld, pp. 9–10. [22] Slums: for publication details, see footnote 8. [23] Branko Milanovic, True world income distribution 1988 and 1993, World Bank, New York 1999. Milanovic and his colleague Schlomo Yitzhaki are the first to calculate world income distribution based on the household survey data from individual countries. [24] UNICEF, to be fair, has criticized the IMF for years, pointing out that ‘hundreds of thousands of the developing world’s children have given their lives to pay their countries’ debts’. See The State of theWorld’s Children, Oxford 1989, p. 30. [25] Slums, p. 6. [26] Such a study, one supposes, would survey, at one end, urban hazards and infrastructural breakdown and, at the other, the impact of climate change on agriculture and migration. [27] Prunty, Dublin Slums, p. 2. [28] Slums, p. 12. [29] Slums, pp. 2–3. [30] See A. Oberai, Population Growth, Employment and Poverty in Third World Mega-Cities, New York 1993, p. 28. In 1980 the 0–19 cohort of big OECD cities was from 19 to 28 per cent of the population; of Third World mega-cities, 40 to 53 per cent. [31] Slums of the World, pp. 33–4. [32] Simon, ‘Urbanization in Africa’, p. 103; and Jean-Luc Piermay, ‘Kinshasa: A reprieved mega-city?’, in Rakodi, Urban Challenge, p. 236. [33] Sabir Ali, ‘Squatters: Slums within Slums’, in Prodipto Roy and Shangon Das Gupta, eds, Urbanization and Slums, Delhi 1995, pp. 55–9. [34] Jonathan Rigg, Southeast Asia: A Region in Transition, London 1991, p. 143. [35] Slums of the World, p. 34 [36] Salah El-Shakhs, ‘Toward appropriate urban development policy in emerging mega-cities in Africa’, in Rakodi, Urban Challenge, p. 516. [37] Daily Times of Nigeria, 20 October 2003. Lagos has grown more explosively than any large Third World city except for Dhaka. In 1950 it had only 300,000 inhabitants but then grew almost 10 per cent per annum until 1980, when it slowed to about 6%—still a very rapid rate—during the years of structural readjustment. [38] Amy Otchet, ‘Lagos: the survival of the determined’, UNESCO Courier, June 1999. [39] Slums, p. 50. [40] Winter King, ‘Illegal Settlements and the Impact of Titling Programmes,’ Harvard Law Review, vol. 44, no. 2, September 2003, p. 471. [41] United Nations, Karachi, Population Growth and Policies in Megacities series, New York 1988, p. 19. [42] The absence of infrastructure, however, does create innumerable niches for informal workers: selling water, carting nightsoil, recycling trash, delivering propane and so on. [43] World Resources Institute, World Resources: 1996–97, Oxford 1996, p. 21. [44] Slums of the World, p. 25. [45] Slums, p. 99. [46] Slums of the World, p. 12. [47] For an exemplary case-study, see Greg Bankoff, ‘Constructing Vulnerability: The Historical, Natural and Social Generation of Flooding in Metropolitan Manila’, Disasters, vol. 27, no. 3, 2003, pp. 224–38. [48] Otchet, ‘Lagos’; and Li Zhang, Strangers in the City: Reconfigurations of Space, Power and Social Networks within China’s Floating Population, Stanford 2001; Alan Gilbert, The Latin American City, New York 1998, p. 16. [49] Martin Ravallion, On the urbanization of poverty, World Bank paper, 2001. [50] Slums, p. 28. [51] Slums of the World, p. 12. [52] Fidelis Odun Balogun, Adjusted Lives: stories of structural adjustment, Trenton, nj 1995, p. 80. [53] The Challenge of Slums, p. 30. ‘Urban bias’ theorists, like Michael Lipton who invented the term in 1977, argue that agriculture tends to be undercapitalized in developing countries, and cities relatively ‘overurbanized’, because fiscal and financial policies favour urban elites and distort investment flows. At the limit, cities are vampires of the countryside. See Lipton, Why Poor People StayPoor: A Study of Urban Bias in World Development, Cambridge 1977. [54] Quoted in Tony Killick, ‘Twenty-five Years in Development: the Rise and Impending Decline of Market Solutions’, Development Policy Review, vol. 4, 1986, p. 101. [55] Deborah Bryceson, ‘Disappearing Peasantries? Rural Labour Redundancy in the Neoliberal Era and Beyond’, in Bryceson, Cristóbal Kay and Jos Mooij, eds, Disappearing Peasantries? Rural Labour in Africa, Asia and Latin America, London 2000, p. 304–5. [56] Ha-Joon Chang, ‘Kicking Away the Ladder: Infant Industry Promotion in Historical Perspective’, OxfordDevelopment Studies, vol. 31, no. 1, 2003, p. 21. ‘Per capita income in developing countries grew at 3 per cent per annum between 1960 and 1980, but at only about 1.5 per cent between 1980 and 2000 . . . Neoliberal economists are therefore faced with a paradox here. The developing countries grew much faster when they used ‘bad’ policies during 1960–80 than when they used ‘good’ (or least ‘better’) policies during the following two decades.’ (p. 28). [57] Slums, p. 48. [58] Carole Rakodi, ‘Global Forces, Urban Change, and Urban Management in Africa’, in Rakodi, Urban Challenge, pp. 50, 60–1. [59] Piermay, ‘Kinshasa’, p. 235–6; ‘Megacities’, Time, 11 January 1993, p. 26. [60] Michael Mattingly, ‘The Role of the Government of Urban Areas in the Creation of Urban Poverty’, in Sue Jones and Nici Nelson, eds, Urban Poverty in Africa, London 1999, p. 21. [61] Adil Ahmad and Ata El-Batthani, ‘Poverty in Khartoum’, Environment and Urbanization, vol. 7, no. 2, October 1995, p. 205. [62] Alain Dubresson, ‘Abidjan’, in Rakodi, Urban Challenge, pp. 261–3. [63] World Bank, Nigeria: Country Brief, September 2003. [64] UN, World Urbanization Prospects, p. 12. [65] Luis Ainstein, ‘Buenos Aires: a case of deepening social polarization’, in Gilbert, Mega-City in LatinAmerica, p. 139. [66] Gustavo Riofrio, ‘Lima: Mega-city and mega-problem’, in Gilbert, Mega-City in LatinAmerica, p. 159; and Gilbert, Latin American City, p. 73. [67] Hamilton Tolosa, ‘Rio de Janeiro: Urban expansion and structural change’, in Gilbert, Mega-City in LatinAmerica, p. 211. [68] World Bank, Inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean, New York 2003. [69] Orlandina de Oliveira and Bryan Roberts, ‘The Many Roles of the Informal Sector in Development’, in Cathy Rakowski, ed., Contrapunto: the Informal Sector Debate in Latin America, Albany 1994, pp. 64–8. [70] Christian Rogerson, ‘Globalization or informalization? African urban economies in the 1990s’, in Rakodi, Urban Challenge, p. 348. [71] Slums, p. 2. [72] Albert Park et al., ‘The Growth of Wage Inequality in Urban China, 1988 to 1999’, World Bank working paper, February 2003, p. 27 (quote); and John Knight and Linda Song, ‘Increasing urban wage inequality in China’, Economics of Transition, vol. 11, no. 4, 2003, p. 616 (discrimination). [73] Slums, p. 34. [74] Shaohua Chen and Martin Ravallion, How Did the World’s Poorest Fare in the 1990s?, World Bank paper, 2000. [75] See my Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World, London 2001, especially pp. 206–9. [76] Slums, pp. 40, 46. [77] Keith Hart, ‘Informal income opportunities and urban employment in Ghana’, Journal of ModernAfrican Studies, 11, 1973, pp. 61–89. [78] Alejandro Portes and Kelly Hoffman, ‘Latin American Class Structures: Their Composition and Change during the Neoliberal Era’, Latin American Research Review, vol. 38, no. 1, 2003, p. 55. [79] Slums, p. 60. [80] Cited in the Economist, 21 March 1998, p. 37. [81] Dennis Rondinelli and John Kasarda, ‘Job Creation Needs in Third World Cities’, in Kasarda and Allan Parnell, eds, Third World Cities: Problems, policies and prospects, Newbury Park, ca 1993, pp. 106–7. [82] Slums, p. 103. [83] Guy Mhone, ‘The impact of structural adjustment on the urban informal sector in Zimbabwe’, Issues inDevelopment discussion paper no. 2, International Labour Office, Geneva n.d., p. 19. [84] Slums, p. 104. [85] Orlandina de Oliveira and Bryan Roberts rightly emphasize that the bottom strata of the urban labour-force should be identified ‘not simply by occupational titles or whether the job was formal or informal, but by the household strategy for obtaining an income’. The mass of the urban poor can only exist by ‘income pooling, sharing housing, food and other resources’ either with kin or landsmen. (‘Urban Development and Social Inequality in Latin America’, in Gugler, Cities in the Developing World, p. 290.) [86] Statistic on street kids: Natural History, July 1997, p. 4. [87] Dubresson, ‘Abidjan’, p. 263. [88] Rogerson, ‘Globalization or informalization?’, p. 347–51. [89] Bryceson, ‘Disappearing Peasantries’, pp. 307–8. [90] In Clifford Geertz’s original, inimitable definition, ‘involution’ is ‘an overdriving of an established form in such a way that it becomes rigid through an inward over-elaboration of detail’. (Agricultural involution: Social development and economic change in twoIndonesian towns, Chicago 1963, p. 82.) More prosaically, ‘involution’, agricultural or urban, can be described as spiralling labour self-exploitation (other factors fixed) which continues, despite rapidly diminishing returns, as long as any return or increment is produced. [91] John Walton, ‘Urban Conflict and Social Movements in Poor Countries: Theory and Evidence of Collective Action’, paper to ‘Cities in Transition Conference’, Humboldt University, Berlin, July 1987. [92] Kurt Weyland, ‘Neopopulism and Neoliberalism in Latin America: how much affinity?’, Third World Quarterly, vol. 24, no. 6, 2003, pp. 1095–115. [93] For a fascinating if frightening account of Shiv Sena’s ascendancy in Bombay at the expense of older Communist and trade-union politics, see Thomas Hansen, Wages of Violence: Naming and Identity in Postcolonial Bombay, Princeton 2001. See also Veena Das, ed., Mirrors of Violence: Communities, Riots and Survivors in South Asia, New York 1990. [94] Hugh McLeod, Piety and Poverty: Working-Class Religion in Berlin, London and New York, 1870–1914, New York 1996, pp. xxv, 6, 32. [95] Ignacio Ramonet, ‘Le Maroc indécis’, Le Monde diplomatique, July 2000, pp. 12–13. Another former leftist told Ramonet: ‘Nearly 65 per cent of the population lives under the poverty line. The people of the bidonvilles are entirely cut off from the elites. They see the elites the way they used to see the French.’ [96] In his controversial sociological interpretation of Pentecostalism, Robert Mapes Anderson claimed that ‘its unconscious intent’, like other millenarian movements, was actually ‘revolutionary’. (Vision of theDisinherited: The Making of American Pentecostalism, Oxford 1979, p. 222.) [97] Anderson, Vision of the Disinherited, p. 77. [98] R. Andrew Chesnut, Born Again in Brazil: The Pentecostal Boom and the Pathogens of Poverty, New Brunswick 1997, p. 29. On the historical associations of Pentecostalism with anarchism in Brazil, see Paul Freston, ‘Pentecostalism in Latin America: Characteristics and Controversies’, Social Compass, vol. 45, no. 3, 1998, p. 342. [99] David Maxwell, ‘Historicizing Christian Independency: The Southern Africa Pentecostal Movement, c. 1908–60’, Journal of African History 40, 1990, p. 249; and Jean Comaroff, Body of Power, Spirit of Resistance, Chicago 1985, p. 186. [100] Chesnut, Born Again, p. 61. Indeed, Chesnut found that the Holy Ghost not only moved tongues but improved family budgets. ‘By eliminating expenditures associated with the male prestige complex, Assembelianos were able to climb from the lower and middle ranks of poverty to the upper echelons, and some Quandrangulares migrated from poverty . . . to the lower rungs of the middle class’: p. 18. [101] ‘In all of human history, no other non-political, non-militaristic, voluntary human movement has grown as rapidly as the Pentecostal-Charismatic movement in the last twenty years’: Peter Wagner, foreward to Vinson Synan, The Holiness-Pentecostal Tradition, Grand Rapids 1997, p. xi. [102] The high estimate is from David Barret and Todd Johnson, ‘Annual Statistical Table on Global Mission: 2001,’ International Bulletin of Missionary Research, vol. 25, no. 1, January 2001, p. 25. Synan says there were 217 million denominated Pentecostals in 1997 (Holiness, p. ix). On Latin America, compare Freston, ‘Pentecostalism’, p. 337; Anderson, Vision of the Disinherited; and David Martin, ‘Evangelical and Charismatic Christianity in Latin America’, in Karla Poewe, ed., Charismatic Christianity as a Global Culture, Columbia 1994, pp. 74–5. [103] See Paul Gifford’s brilliant Christianity and Politics in Doe’s Liberia, Cambridge 1993. Also Peter Walshe, Prophetic Christianity and the Liberation Movement in South Africa, Pietermaritzburg 1995, especially pp. 110–1. [104] Jefrey Gamarra, ‘Conflict, Post-Conflict and Religion: Andean Responses to New Religious Movements’, Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2000, p. 272. Andres Tapia quotes the Peruvian theologian Samuel Escobar who sees Sendero Luminoso and the Pentecostals as ‘flip sides of the same coin’—‘both were seeking a powerful break with injustices, only the means were different.’ ‘With Shining Path’s decline, Pentecostalism has emerged as the winner for the souls of poor Peruvians.’ (‘In the Ashes of the Shining Path’, Pacific News Service, 14 Feburary 1996). [105] Freston, ‘Pentecostalism’, p. 352. [106] Comaroff, Body of Power, pp. 259–63 |

April

29 2004 |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Printer Friendly Version | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| |

|||||||||

| |

|||||||||