|

It

happens every ten years. The United States conducts a census—a

systematic set of procedures we use to count the number of people

living in the country. Mandated in Article I, Section II of the U.S.

Constitution, the census was established in 1790 as the official

method for determining the actual number of people living in the U.S.

whether in residential structures, institutions or living unhoused.

The

framers of the Constitution wanted an accurate count because this

number would then be used to determine the number of congressional

representatives apportioned to each state. From their perspective,

this number determined how much political power each state would

claim.

The

battle for power among the framers was fierce. States that relied on

a plantation economy that were heavily populated with slaves. Their

representatives insisted that slaves be counted in the census, which

would give the south more congressional representation. The northern

states didn’t want the slaves counted at all. In the end, a

compromise was reached. The 3/5ths Compromise, as it was called, is

found in Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3 of the United States

Constitution, which reads:

Representatives

and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which

may be included within this Union, according to their respective

Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of

free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years,

and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.

The

Census Act of 1790 mandated that everyone except untaxed Indians be

counted. It states,

“The

marshals of the several districts of the United States shall be, and

they are hereby authorized and required to cause the number of the

inhabitants within their respective districts to be taken; omitting in

such enumeration Indians not taxed, and distinguishing free persons

including those bound to service for a term of years, from all others;

distinguishing also the sexes and colours of free persons, and the free

makes of sixteen years and upwards from those under that age;”

In

1868 the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution repealed the 3/5

Compromise thereby including 100% of all formerly enslaved people in

the census count. In 1879 a new census act mandated that Indians not

taxed (Indians living on reservations or unsettled areas) also be

included in the census. With these two changes, the census of 1880 was

the first to attempt to count everyone living in the United

States.Today,

the Census Bureau maintains the spirit of the objectives established

in 1879 which was to count everybody – citizens, non-citizen

legal residents, non-citizen long-term visitors and undocumented

immigrants. Americans living abroad who are not members of the armed

forces or working for the government are not included in the census.

Note:

On Tuesday, July 21, 2020, Donald Trump issued a directive to the

U.S. Census Bureau to not count undocumented immigrants in the 2020

census. This directive will likely be challenged on constitutional

grounds but if it is enforced, the political impact would be

significant especially in California, Texas and New York.

Although

census data was originally used almost exclusively to determine

congressional representation and taxes, today, census data is also

used as the basis for determining federal funding allocations,

grants, and other forms of support to states, counties and

communities.

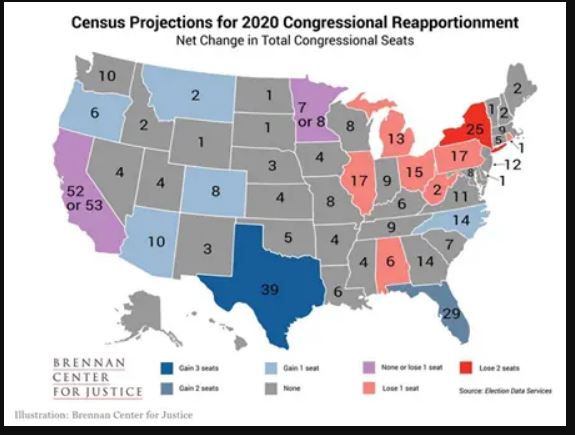

Every

ten years, after the completion of the census the President is

required, by law, to report the census results to Congress. These

results may change the number of congressional seats in each state.

The governors of each state are then informed of the number of seats

his or her state is entitled. The state legislatures then redraw the

state’s congressional districts.

Congress

set the size of the House of Representatives at 435 voting members.

As of the last census, each congressional district was comprised of

roughly Seven Hundred Ten thousand people.

Here

is what is rarely discussed – Some argue that the modern-day

Census Bureau maintains the spirit of the Census Act of 1790 even as

it applies to the 3/5th compromise.

In

her groundbreaking book, “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration

in the Age of Colorblindness”, author and civil rights attorney

Michelle Alexander introduces her readers to a contemporary practice

she likens to the 3/5th compromise—Prison Based Gerrymandering.

For

those unfamiliar, the Three-Fifths Compromise was a deal struck

between the southern states and the northern states during the 1787

United States Constitutional Convention. To claim a larger population

and thereby be entitled to a greater number of congressional

representatives and more power, southern states wanted to count

slaves as if they were constituents, northern states opposed this

idea. They were at a stalemate. To strike a deal the solution they

agreed upon was to count three out of every five slaves as people.

This gave the Southern states a third more seats in Congress and a

third more electoral votes than if slaves had been ignored.

Today,

according to Alexander, most states census residence rules require

that incarcerated people be counted at their place of incarceration

as opposed to their home address. Like the slaves, the incarcerated

cannot vote in 48 states.

Mass

incarceration, a phenomenon that did not exist in 1790, has resulted in

major population shifts. The overwhelming majority of incarcerated

people in the U.S. come from urban areas while the prisons are

typically built in non-urban or rural areas.

This

counting practice results in a shift in population from urban center

to rural community thereby increasing the political clout of rural

communities while decreasing the political clout of urban

communities. And, all the while, the incarcerated, almost without

exception, have no say.

In

addressing the census residence rule and specifically prison-based

gerrymandering, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund reports:

Over

the last several decades, the percentage of Americans incarcerated in

prisons has increased four-fold. Incarcerated persons are often held

in areas that are geographically and demographically far removed from

their home communities. For instance, although non-metropolitan

counties contain only 20% of the national population, they host 60%

of new prisons.

In

addition, because Latinos and African Americans are incarcerated at

three to seven times the rate of Whites, where incarcerated people

are counted has tremendous implications for how African-American and

Latino populations are reflected in the census, and, consequently,

how these communities are impacted through redistricting.

Political

districts are based on population size. The number of people in a

geographical region determines the number of Congressional, state,

and local representatives. When prison-based gerrymandering is

employed, district lines redrawn to accommodate new census figures

result in large portions of what would have been urban populations

being reapportioned to rural counties and distorts democracy.

Because

of this practice, urban communities, particularly urban communities

of color stand to lose the most. Census figures help determine where

government money will go to fund hospitals, school services, public

housing, social services, food stamps and other programs. As

mentioned, the census figures are also used to determine how many

seats each state has in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Prison-based gerrymandering may result in the loss of both federal

dollars and political representation for districts that are already

struggling.

Prison-based

Gerrymandering also defies most state constitutions and statutes,

which explicitly state that incarceration does not change a

residence.

Data

gleaned from the 2020 census will be used to help direct $1.5

trillion per year in federal funding for programs like Medicare,

Medicaid, Head Start, Title I and the National School Lunch Program.

The data is also used to help officials to determine individual and

organizational eligibility for these programs.

By

counting incarcerated people as residents of the towns where they are

confined, those towns stand to receive a benefit that rightfully should

go to the community the incarcerated person calls home and where they

will ultimately return.

|