|

"There

are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks when decades

happen.”

-

V.I. Lenin

The

Columbia University Struggle of 1968, 50 years ago, was in fact a

Struggle against Columbia University—as a ruling class

slumlord, a racist gentrifier against the people of Harlem and

Morningside Heights, and a genocidal war criminal carrying out

weapons research against the People of Vietnam. It was one of the

great miracles of the times that students who had been recruited to

support The System turned against it and sided with the Black

community and the people of Vietnam.

The

Struggle against Columbia was carried out by The Movement—a

Black United Front in Harlem including Harlem Tenants Association,

Morningsiders United and Harlem CORE, the Students’

Afro-American Society and Black Students of Hamilton Hall, Students

for a Democratic Society at Columbia, and national groups like

Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, SDS, with support from

the national civil rights and anti-war movements.

The

Movement demanded that the University stop construction of a

gentrifying gymnasium in Morningside Park, opposed by the residents

of Harlem and Morningside Heights, who called it Gym Crow, and that

it also withdraw all institutional ties to the Institute for Defense

Analyses (IDA)—a Department of Defense think-tank that

developed weapons to use against national liberation and communist

insurgencies including the people of Vietnam. The Columbia University

administration, after a two-month struggle, acceded to the core

demands of the struggle—an unequivocal victory for The Movement

at the time.

The

Columbia Struggle took place in New York, a world city, and Harlem,

the national capital of the Black Nation. The Movement gained

prestige by taking on such high profile adversaries on a world stage

—the Columbia ruling class, Mayor John Lindsay, the New York

Times, and the New York Police Department. Its historic victory was

shaped by the protracted nature of the conflict over years

culminating in two intense months and the consistent ability of its

Black and white leadership to solve the many challenges in the

organizing process. The Movement built and sustained a broad united

front of Black and white anti-racist, anti-war forces to stay on

message against Gym Crow and the Institute for Defense Analyses, keep

the heat on the university administrators and trustees, and isolate

careerist white students and faculty who tried to capitulate on the

core demands in favor of "student power" and a

"restructured university."

Through

the struggle Black Harlem residents, Black students at Columbia and

Barnard College, and white anti-racist anti-war students came to see

even more clearly that institutional racism and imperialism were not

just things that Columbia did, but rather were the very essence of

the university's role in capitalist society—including training

its students to become the future administrators and leaders of the

U.S. Empire.

The

struggle took place in the revolutionary year of 1968. in which the

United States was losing all moral credibility in the world, and when

students, teachers, workers, women of all races were in revolt shaped

by a world and Third World revolutionary energy and optimism. Like a

revolutionary feedback loop, Columbia in turn contributed to the

revolutionary energy and power of the world movement against the

military and political hegemony of the U.S. Empire. Many students at

Columbia and Barnard, armed with the moral imperatives of the time,

fighting for the key demands of that campaign, and experiencing mass

police repression of their movement came to understand that the

struggle against Columbia was also a fight against The System and

that in turn raised their determination and morale.

Fifty

years ago I came to Columbia as a national organizer for SDS and

worked closely with the SDS chapter leadership for over a month to

build greater support for the struggle and the Six Demands. I was so

moved that in August 1968 I wrote a long article that was published

in Our Generation, a Canadian radical magazine, and later The

Movement, a publication of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating

Committee, about what I believed were the lessons of Columbia, going

into great and at times minute detail from an organizers perspective.

. I focused on Columbia because it had deeply impacted my views,

radicalized me further, as all events at that time in history did,

and because I believed in analyzing social movements to lay the

historical record. Today, I have spent the last 3 months re-studying

the Columbia struggle, reading Stefan Bradley's excellent Harlem

versus Columbia: Black Student Politics in the late 1960s and

every essay in A Time To Stir, edited by Paul Cronin, a

valuable compendium of Columbia participants, to reground my

historical perspective and re-examine my own role in that struggle. I

think The Struggle Against Columbia is worth that level of engagement

as it provides such a positive model of a Black/white anti-racist,

anti-imperialist mass campaigns on such a large historical stage. And

as I have seen clearly by reading so many conflicting interpretations

of history—where not surprisingly of course I side with the

Black view of that struggle including its many united front voices

and dedicated white comrades—there is no such thing as

"history" but only the battle over historical

interpretation, and this article is my contribution to that battle.

Key

Events in the Struggle Against Columbia

The

Struggle Against Columbia was a confrontation with Columbia

University's reactionary role in U.S. society. If the decisive event

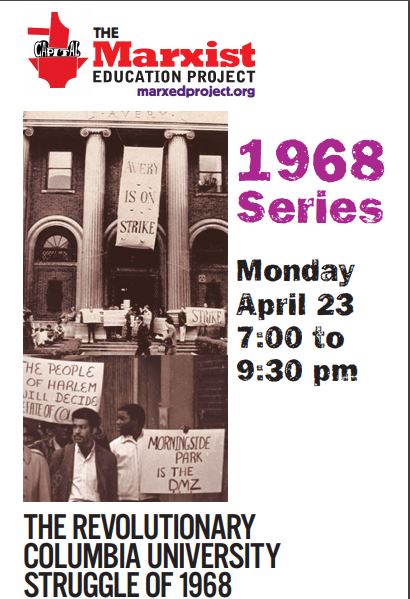

in the Columbia struggle was the SAS/SDS occupation of Hamilton Hall

on April 23, 1968 that its participants will describe in these pages,

that larger struggle had deep and long roots in protests against the

University:

1)

Tenants in Harlem and Morningside Heights had a long history of

struggle against Columbia the Slumlord throughout the 1960s.

2)

Black groups and Morningside Heights neighborhood community and

tenant activists had been opposing Columbia's building of a gym in

Morningside Park in Harlem since it was proposed in 1961.

3)

Anti-war faculty and students had been protesting Columbia role in

weapons research and Columbia's complicity with CIA and military

recruiters and U.S. genocide in Vietnam since the mid-1960s.

The

concepts of moral responsibility and confronting complicity drove the

Columbia Struggle.

As

the movement against the war in Vietnam strengthened after 1965,

organizers researched and challenged the structural connections

between U.S. racism and atrocities, the larger society and the

institutions in which they lived, worked, and studied. People

started to say, "my church or university is complicit in war

crimes” and "I don't want be complicit through benefitting

from the system or by being passive or silent in the face of

injustice."

In

April 1965, at the SDS March on Washington Against the Vietnam War,

Bob Moses, SNCC leader, said that Vietnam and Mississippi were two

fronts in a world movement against racism and colonialism and

challenged us to "make the connection between segregation in the

South and U.S. defoliation in the Third World."

In

March 1967, Bob Feldman, an SDS researcher, discovered that Columbia

was institutionally affiliated with the Institute for Defense

Analyses, whose Jason Division of U.S. university faculty members

was doing Vietnam War-related research on weapons for the Department

of Defense to be used against native peoples in the Third World.

Professor Seymour Melman, a prominent anti-nuclear and anti-war

figure, exposed the university as an appendage of the military state

in that some faculty were involved in the production of nerve gas,

and that 50 percent of the University's budget was paid by the DOD,

Atomic Energy Commission and NASA. SDS and anti-war students

challenged CIA recruitment on the campus and raised the charge that

Columbia was directly involved in crimes against humanity against the

people of Vietnam.

On

April 1967, at Riverside Church blocks away from Columbia, Dr. Martin

Luther King gave his most forceful statement opposing the U.S. war

against the people of Vietnam. Breaking the Silence, he said "There

are times when silence is betrayal" and called the United

States, "the greatest purveyor of violence in the world."

By

February 1968, Columbia finally began construction of its gymnasium,

put a fence around the site and began digging. Black community

groups called on Columbia to stop construction of the gym altogether.

H. Rap Brown and other national Black liberation and civil rights

leaders joined Harlem groups. Black students at Columbia made the

fight against Gym Crow a high visibility Harlem, city-wide and

national campaign.

Still,

in the spring of 1968, the demands against Columbia—stopping

construction of the Gym and cutting all ties to IDA—were not

yet part of a coherent campaign nor was there an agreed upon tactical

plan to even imagine winning those demands.

In

an irony of history, only a few days before the April 23, 1968

demonstrations and occupation, both SAS and SDS worried that

the campus was not ready to move aggressively to confront Columbia on

Gym Crow and the IDA before the end of the school year.

As Ray Brown of SAS describes in his essay, "Race and the

Specter of Strategic Blindness" in A Time to Stir,

"Mark

Rudd or Juan Gonzales asked William Sales and myself to attend a

meeting to discuss whether there would be any further demonstrations

about the Gym before the graduation of 1968...We unanimously agreed

that the student body was tired, apathetic, and unlikely to engage

further on the issue. There was agreement however that we should give

it one final joint rally at the Sundial."

As

Brown explains, first the students tried to occupy Low Library but it

was locked down. Then someone yelled, "To the Gym" and the

Black and white students marched there only to discover, "a hole

in the ground provides a poor prop for a demonstration" and then

the group moved to have a "teach-in" that soon became an

occupation of Hamilton Hall.

There,

the Black and white students understood they were moving from a

protest to a serious and possibly protracted occupation of Columbia

buildings. Later that day, The Black Students of Hamilton Hall

decided they wanted an exclusively Black site to strengthen their own

perspective, presence, and independent role in the overall protest

and asked the whites to "find other buildings to occupy."

SDS leaders agreed and moved on to occupy Low Memorial Library,

Mathematics, Avery, and Fayerweather. The Black and white SAS and SDS

agreed on what would be called The Six Demands:

1.

That the administration grant amnesty for the original “IDA 6”

and for all those participating in these demonstrations. 2. That

construction off the gymnasium in Morningside Park be terminated

immediately. 3. That the university sever all ties with the Institute

for Defense Analyses and that President Kirk and Trustee Burden

resign their positions on the Executive Committee of that institution

immediately. 4. That President Kirk’s ban on indoor

demonstrations be dropped. 5. That all future judicial decisions be

made by a student-faculty committee. 6. That the university use its

good offices to drop charges against all people arrested in

demonstrations at the gym site and on campus.

Inside

the occupied buildings more than 100 Black and 700 white students

practiced self-government, engaged in deep personal conversations and

for many, lifetime transformations, and formed the nucleus of a

larger and sustained resistance to Columbia administration and

support for the Six Demands.

On

April 30, at 2:30 in the morning, after a week of the mass

occupations, the University and New York Mayor Lindsay called in a

massive, armed-to-the teeth, New York Police Department force to

forcibly evacuate the students. The Black students, painfully aware

of police brutality, and with the power of Harlem and the recent

urban rebellion surrounding them, negotiated an orderly withdrawal

from Hamilton. The white students were met by a police riot in which

many people were arrested and beaten. The campus, already supportive

of the two major demands to Stop Gym Crow and Stop IDA, became even

more supportive of the occupiers.

After

"the police bust" SAS and SDS called a student/university

strike, the university cancelled classes for the rest of the year.

Now, SAS and SDS built a broad united front to support the Six

Demands, went from occupying the buildings to occupying the

university, initiated city-wide demonstrations in support of other

social justice causes including support for Harlem and Morningside

Heights tenants fighting Columbia as a slumlord, and organized a

Liberation School as an alternative to corporate, imperialist

education involving as many as 1,000 students participating.

Through

a complex process of protest, mobilization, community organizing,

counter-institution building, independent media such as Liberation

News Service and Harlem and Black publications, and great city-wide

and national support The Movement,led by the Harlem Community, SAS,

and SDS, was able to take on the Columbia ruling class, New York

Times, Mayor Lindsay, and the NYPD—and win. Miraculously,

Columbia accepted the demands of the Movement. The University agreed

to stop all construction of the Gym in Harlem. The University agreed

to break all institutional connections with the Institute for Defense

Analyses.

The

Columbia Struggle as a Civil Rights, Black Liberation, and Anti-war

Campaign led by the Black community

The

Struggle Against Columbia University in April and May 1968 was a

civil rights and anti-war struggle as part of a national and

international movement. It was led by a powerful alliance of the

Black community nationally and in Harlem, the Students' Afro-American

Society (SAS), Black Students of Hamilton Hall, and Students for a

Democratic Society (SDS)—a national, white, radical, civil

rights anti-war student organization and its Columbia-Barnard

chapter. It was not a Columbia University and Barnard

College-student-centered struggle as much as broad united front

inside and outside Columbia against the University as a slumlord,

racist gentrifier, and human rights violator.

The

year 1968 was a momentous year marked by epochal world events. Three

events among many shaped the Columbia struggle.

*

In January 1968 the Vietnamese National Liberation Front carried out

the Tet Offensive: a brilliant coordinated attack against South

Vietnamese targets and U.S. troops including seizing the U.S. embassy

in Saigon—the NLF had a great sense of symbolism. This shocked

the world into finally understanding that the struggle led by the

National Liberation Front and the Communist Party of Vietnam would

win the war—and members of U.S. ruling circles began to discuss

how to end it.

*

On March 31, 1968 President Lyndon Johnson announced he would not run

for re-election as a reflection of the powerful anti-war sentiments

against him and growing anti-war Democratic Party insurgencies

against him by Senator Eugene McCarthy with Senator Robert Kennedy

also waiting in the wings.

*

On April 4, 1968, in what many believe was a FBI, right-wing plan,

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis Tennessee, a

year to the day after his passionate anti-Vietnam war speech "Beyond

Vietnam—A Time to Break Silence.” His murder led to the

largest national outbreak of urban rebellions in Black communities

all over the U.S. including in neighboring Harlem. While a few made

facile statement like, "Well, that's the end of non-violence,"

in fact King’s assassination was a devastating blow to the

Black movement, the U.S. and world left. We had lost our finest

leader who had the unique ability to effectively confront the federal

government and the Democratic Party and was killed precisely because

of that gift.

On

April 23, 1968, the day of the dramatic escalation of the Struggle

Against Columbia, the civil rights, Black Liberation, anti-Vietnam

war, and Third World movements inside and outside the United States

were filled with a sense of outrage, influence, and hope and dreams

of major structural victories against "The System" —aka

U.S. Imperialism.

The

form and content of Black Leadership of the Struggle Against Columbia

University.

In

1968, Columbia University was a private educational institution with

a campus of 8,000 white students where 100 Black students provided

leadership to the surrounding Black community and the white student

movement as well.

SDS—the

white radical student organization dedicated to opposing the U.S. war

against the people of Vietnam was also very supportive of the civil

rights and Black Power movements at the time. Many of its members

had also been members of CORE and Friends of SNCC even before joining

SDS, and the Columbia SDS committee on university expansion headed by

Mike Golash made the struggle against Gym Crow a high priority. In

fact, SDS’s grasp and practice of support for the Black

struggle and the people of Harlem dramatically improved through the

course of the struggle.

In

his important essay "Race and the Specter of Strategic

Blindness" in A Time To Stir, Ray Brown, then a leader of the

SAS and Students of Hamilton Hall, argues that

"The

Black struggle at Columbia was the pivotal act of the Columbia

protest not an ancillary code to a New Left uprising."

As

an active participant in that struggle I understood that at the time

and believe that the vast majority of SDS students did as well.

Today, sadly, 50 years later, a few white,

bitter, ethically impaired, and marginal participants have attacked

the Black students for choosing to make Hamilton Hall an all-Black

site of occupation. I think that is a re-writing of history in which

many white people have moved to the right over their lifetime but

they do not speak for SDS at the time and in some cases are even

rejecting their better selves in their present downward spiral.

The

Fight against Gym Crow--The Black United Front in Harlem with

critical white allies defeated Columbia University

Today

in Harlem and Black communities throughout the U.S., including South

Central Los Angeles where I presently work and organize, the Black

community is under profound attack—dispersed, disoriented,

defensive, at times demoralized. Black communities are under constant

police occupation and a ruthless market system in which an oppressed,

colonized people driven out of the economy can no longer afford to

live in their apartments and homes. Harlem, the most prominent Black

Community in the United States, once the site of white flight, is now

suffering from the invasion of the white gentrifiers.

When

I went to work with the Congress of Racial Equality in 1964 in the

north east, including Harlem, the Civil Rights Movement and the Black

militants had already coined the slogan, "Urban renewal is Negro

removal." As such, the struggle in 1968 for Black residents of

Harlem in alliance with Black students to stand up to a powerful

white university to defeat Gym Crow was a significant and symbolic

victory on its own terms. It was part of the historic struggle of the

times for "Black community control" of schools, police, and

public land—reflected in the historic struggles at IS 201 in

Harlem and the Black communities of Ocean Hill/Brownsville in

Brooklyn.

This

movement for Black self-determination was in direct conflict with the

University's view of itself as the white civilizer of native peoples.

As Stefan Bradley describes in Columbia versus Harlem,

University Provost Jacques Barzun saw the Black community as

"un-inviting, sinister, abnormal, and dangerous." Barzun

felt that Columbia's Negro removal programs were necessary to protect

the safety of white Columbia faculty "and their wives" and

offered a better alternative to the system's only other solution,

"paratroopers in an enemy country."

As

Roger Kahn, in the Battle of Morningside Heights, explained, "In

the 1960s, Columbia, `one of the most aggressive landlords on earth,'

bought 115 residential buildings in West Harlem and Morningside

Heights, and displaced around 6,800 Single-Room-Occupancy [S.R.O.]

tenants and 2,800 apartment tenants, approximately 85 percent of whom

were Black and Puerto Rican."

In

1968, the Ford Foundation gave $10 million to Columbia for community

development that only reinforced their power against the community

while liberal Mayor Lindsay made high sounding statements against

removal and gentrification with no commitment to take on the

university. On the people's side, Architects Renewal Committee in

Harlem put forth radical visions for an alternate future and

grassroots groups continued the protests but there was not sufficient

muscle to stop the voracious university. Since the capitalists

controlled all the financial institutions, the political "power

structure," and the police, and given this ominous balance of

forces, what were Black, Puerto Rican, and low-income people of color

to do?

In

1961 the Columbia University administration, with the support of the

white corporate power structure, went to the New York State

legislature and got them to pass a sweetheart bill to cede, that is,

"rent" two acres of public land in Morningside Park

bordering on Harlem to the university to build a gym for its white

student body and faculty. At the time, Black elected officials State

Senator James L. Watson and Assemblyman Percy Sutton from Harlem

supported it, hoping the project might bring resources to their

constituency.

But,

by 1967, as the gym moved towards groundbreaking and construction,

the reality of the project hit home—Columbia was going to carve

out 2 acres of valuable public park land to build a monument of

segregation. Columbia planned to "allow" the community

access to 15 percent of the gym facilities and hours of operation

and, to punctuate its contempt, offered the residents of Harlem a

segregated "back door" at a lower level at the bottom of

the gym. A growing community resistance called for the cancellation

of the project with the brilliant agitational slogan, "Stop Gym

Crow," in reference to the racist Jim Crow segregation laws.

By

October 1967 Robert McKay of the West Harlem Tenants Association

announced that their members would "throw themselves in front of

the bulldozers" if Columbia did not stop its plans to build the

gym.

In

December 1967 H. Rap Brown, the chair of the Student Non-Violent

Coordinating Committee, in the ascendant language of Black Power,

told a meeting in Harlem,

"If they build the

first story, blow it up. If they sneak back at night and build three

stories, burn it down. If they get 9 stories built, it's yours. Take

it over and maybe we'll let them in on the week-ends."

The

Black students at Columbia, led by the Student Afro-American Society,

made the stopping of the gym their priority. As Raymond Brown,

observed, "As a group we found ourselves more committed to the

Harlem community than Columbia."

Black

artists, revolutionary intellectuals, civil rights, and Black

Liberation organizers helped shape the political and cultural

consciousness of Black Students at Columbia.

SAS

leaders Ray Brown, who later became a prominent attorney challenging

genocide in Africa, and William Sales, who became a prominent Black

scholar at Seton Hall University, explained that the Black students

had frequent interactions with militant civil rights leaders

Courtland Cox, James Bevel, Pan Africanists Queen Mother Moore and

John Henrik Clark, and Black nationalists such as Charles 37X

Kenyatta. The group had also met with James Baldwin, the

revolutionary writer. As Brown recalled,

"Baldwin explained

that our presence at an Ivy League University was more important than

we ourselves realized and that our complaints about our treatment

were minor issues compared to the fact of our presence and the search

for connections to the larger issues."

It

is hard for people today to grasp that those influential Black

leaders who were the celebrities of our time prioritized work with

rank and file and future leaders of grassroots movements and treated

us with great respect. In my own experience with CORE and later as an

organizer with the Newark Community Union Project, we spent hours

listening to Robert Moses, Dave Dennis, Fannie Lou Hamer, Lawrence

Guyot, William Kunstler, and other leaders of CORE, SNCC, and the

Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party who spoke with us about

organizing and movement strategy. As such, Black students came to

understand the significance of their strategic role as a wedge and

even weapon against the University's attacks on their community and

were beneficiaries of the great Black thinkers and revolutionary

worldview of the times—including its internationalist and Pan

Africanist influences. The fact that Chairman Mao Tse-tung sent a

telegram of support for the Black Students of Hamilton Hall is beyond

comprehension today.

Black

independence, Black separatism, Black self-determination and the

decision to ask the whites to leave Hamilton Hall.

The

Black Students of Hamilton Hall found their own voice, their own

independence, their own self-determination, inside Hamilton Hall and

created a Black enclave of self-government that was a model for the

broader movement.

As

Ray Brown explains, once the Black and white students began the

occupation of Hamilton Hall, the Black students began to meet

separately upstairs. Ray Brown, Andrew Newton, William Sales, and

Cicero Wilson formed the steering committee of Black Students of

Hamilton Hall.

"With

surprising clarity and speed we decided to embrace the demands to

cease the construction of the Gym and end the university's ties to

IDA. We also decided to barricade the building and ask the still

disorganized white students to leave and seize other buildings on

your own. Our victories on IDA and the Gym have long been manifest."

As

William Sales explains,

"Inside Hamilton

Hall we experienced true self-determination. Everything that went on

inside the building was a result of decisions we made and had to live

with. It was our larger Black community that literally fed us and

stayed the hand of the police for a week. We ironed out disagreements

and established workable protocols for maintaining the livability of

the building and for democratic decision-making. Our success in

remaining together under those circumstances greatly enhanced our

mutual self-respect. It created for us a visceral experience of what

Black Power and self-determination could be within the larger

society."

Contrary

to the rewriting of history by a few bitter white liberals, the SDS

leadership and supporters, by then 700 strong, along with the vast

majority of Columbia’s white students, fully supported the

decision of the Black Students of Hamilton Hall, saw them as "our

vanguard" and saw their role in occupying Low Library,

Fayerweather, Avery, and Mathematics as their own great achievements.

They saw "take over your own buildings" as a constructive

challenge to expand the support for the Black community, the Black

students, and the people of Vietnam—and had the good sense and

good politics not to get caught up in the false and racist

consciousness of, of all things, "white rejection by Blacks."

In

my hundreds of conversations with SDS members and allies, I did not

sense any resentment of Black self-determination. If anything, I was

already hearing war stories among white students about their great

experiences in Mathematics, Fayerweather and other buildings, the

"commune experience" and how proud they were of SAS and

SDS. And this was just after the NYPD free-for-all attack on the

white students with more than 700 being beaten and arrested where, if

they had any anger it was against the police and the university.

Then, the questions facing the movement were, "What do we do

now? How do we seize the initiative? If we are no longer in the

buildings how do we win our demands? How do we get Columbia to stop

building the gym and carrying out war crimes against the Vietnamese?

Ray

Brown spoke for the Black students and the best of the white students

when he concluded, "Our victories on IDA and the Gym have long

been manifest."

Building

a Black United Front and multi-racial alliance against the gym.

As

one example of the growing power of the Black Power and Black

militant forces inside the Black united front, many of the Black

Democrats who had initially voted to authorize Columbia's building of

the gym, including Percy Sutton who by then had become Manhattan

Borough President, claimed they had been misled by Columbia and went

from token to militant opposition—first proposing compromises

to make the gym more community friendly and then realizing as did

Columbia that the entire project was toxic—and coming out

against the gym altogether. Victor Solomon of Harlem CORE said "the

racist gym" cannot be built. "Harlem is a colony and the

community should impede the progress of the imperialist." What

is again hard to grasp today is that those radical and revolutionary

ideas had great resonance in the Black community and its advocates—in

this case CORE and SNCC knew how to organize, not just put out

rhetoric.

As

William Sales explained,

"I

knew that Black activists could accept many Communist principles if

presented in the context of Third World Liberation. If one used the

words of Fanon, Cabral, Mao, or Nkrumah many blacks would endorse

your position especially when combined with major references to Black

Nationalism."

Again,

the interrelationship with advanced thinkers shaped the clarity and

force of the Black students. As William Sale explained, in his essay,

"Self-determination and self-respect: Hamilton Hall 50 Years

Later,"

"Preston Wilcox of

the School of Social Work faculty helped Ray Brown and myself avoid

the pitfalls of opportunism around the issue of the gymnasium. We

initially conceded that community folks and their student allies were

too weak to oppose the construction of the gym. Our position was that

Columbia could be pressured to increase the size and amenities of the

gym structure but it was too late to force them to abandon the notion

of two separate gyms within one shell. Preston was adamant, and won

us over to the position, that the struggle was against any form of

Jim Crow building, not about getting a better deal within an

essentially Jim Crow arrangement."

SDS

and white students were critical elements of the Gym victory.

While

SAS and the Black students at Hamilton Hall drove the Gym campaign,

the aggressive support of SDS was critical. This was a white

university in a white society and white students were 90 percent of

the student body. Initially, SDS, from my reading of that history

and my participation in the struggle, focused more on opposition to

the war in Vietnam and ending the University's role with the CIA,

DOD, and the Institute for Defense Analyses. But the power of the

Black movement and Harlem made the gym a compelling issue and central

to the strike and the campaign.

By

April 23, the famous Last Chance Demonstration, as Black and white

students marched together, the chants were "let's take Low

Library" followed by "let's go the gym site" followed

by "let's take Hamilton Hall." In a few hours The Gym and

the IDA were joined together for posterity.

We

can be assured that if the Columbia ruling class felt any tension or

conflict between the Black and white movements on the core demands of

the strike, it would have exploited them to its own benefit. In my

own work at Columbia, I and other SDS leaders challenged white

students who said, after the police raid on campus, "I support

the strike, but... I want student power and a restructured university

and do not want to be bound by the two main demands of the

campaign--the Gym and IDA."

We

at SDS vehemently replied that The Strike was about racism and war

and Columbia's role in it. For some liberal and careerist whites to

say they supported a "strike" but not the demands of the

Struggle was in fact supporting Columbia's racism and imperialism and

selling out the people of Harlem and Vietnam. We did not want a

"restructured university" —we wanted a specific end

to specific racist and imperialist policies and institutional

arrangements by the university.

To

their credit, the vast majority of white students agreed and rallied

behind the powerful moral arguments of the Campaign. By the end of

the struggle, when Columbia finally announced it would end the gym

project--Gym Crow--once and for all and withdraw from IDA, it was a

testament to the broad, multi-racial, progressive, radical, and

revolutionary united front led by the Black community and students.

It was the dialectical relationship between Black ideas, Black

community forces, Black students, and a broad and militant support

from the white and vast majority of Columbia/Barnard university

students and again the revolutionary conditions of 1968 and that

period in history that turned the tide for such an unequivocal

victory.

William

Sales summarizes the spirit and achievements of unity/struggle/unity

in Black/white relationships that successfully defeated the Columbia

ruling class.

"Black students at

Hamilton Hall did not split with the agenda of the white students. We

endorsed the demands of the strike and never wavered from that

position. There were however, important tactical considerations that

could not be ignored. We felt that white students underestimated the

violence that the system was capable of directing at its own citizens

when challenged. Black students knew this from the beginning. As a

small minority of the student body Blacks did not want mere numbers

to swallow up their presence in the demonstration. In addition, our

smaller numbers and stronger mutual familiarity allowed us to arrive

at firm consensus significantly quicker than our white counterparts.

Stylistically, the ultra-democracy of SDS with the amorphous,

fluctuating white membership in the strike was a protest style we

wanted no part of. It appeared to us to be anarchic.

I personally respected

the SDS leadership. The need to keep cohesion among their

constituency was a monumental task that they should be praised for

executing. Their self-sacrifice and adherence to a principled

position in support of oppressed people of color, in Harlem as well

as Vietnam, commanded our respect. No decision to assume separate

tactical headquarters should imply we were not allies in the same

fight."

From

Protest to Strike to Campaign to Victory

On

April 30 after a week of student occupation of the university, the

New York City Police Department (NYPD) arrested more than 700

students—500 men and 200 women. The SAS and SDS leaders enjoyed

significant popular support but Columbia administration had not

agreed to meet their demands. In response to the "police bust"

there was even more support for the movement and SAS and SDS proposed

and thousands agreed it was time to go on Strike. But what was the

tactical plan? What did a strike look like? How could the movement

win its demands and sustain the momentum of the occupations? Again,

the Six Demands were debated, discussed, and dissected.

The

Six Demands as a Definition of Politics

1.

That the administration grant amnesty for the original “IDA 6”

and for all those participating in these demonstrations.

2.

That construction of the gymnasium in Morningside Park be terminated

immediately.

3.

That the university sever all ties with the Institute for Defense

Analyses and that President Kirk and Trustee Burden resign their

positions on the Executive Committee of that institution immediately.

4.

That President Kirk’s ban on indoor demonstrations be dropped.

5.

That all future judicial decisions be made by a student-faculty

committee.

6.

That the university use its good offices to drop charges against all

people arrested in demonstrations at the gym site and on campus.

When

I arrived at Columbia, Mark Rudd, Juan Gonzales, and other SDS

leaders explained the challenge. They said that while the Black

students of SAS and SDS had won the respect of the majority of the

campus, they worried that the more militant forces could be isolated

as more moderate forces, closely aligned with the University

administration, had joined "the strike" but were not

committed to stopping the Gym or ending the university's ties to IDA.

We all knew this was history in the making but how could we turn a

great protest into a structural victory?

As

one example, a new group, "Students for a Restructured

University" (which received $40,000 in funding from the Ford

Foundation, whose then-president, McGeorge Bundy, was a former

Johnson White House National Security Affairs Advisor) said that SDS

was turning people off with talk about "racism and imperialism"

and argued that Columbia was in fact a "community of scholars."

They put themselves forward as a competing political force and tried

to negotiate a separate and unprincipled peace with the Columbia

administration telling the public that SAS/SDS did not speak for the

(white) students. But what about the interests of the people of

Harlem and the people of Vietnam--would these privileged white

students from an imperialist Ivy League University, some of them with

their own imperialist aspirations, sell out the movement? At the

time, the answer was "very possibly, if not probably, if we

don't continue to provide political leadership."

The

struggle for the political leadership of the Columbia Strike

SDS

and SAS proposed that the strike committee be expanded from the 100

Black occupiers and 700 white occupiers. They agreed that the Black

students would get 3 delegates, a ratio more than a literal counting

of the 100 Black students who occupied Hamilton. Today it seems

shocking that SDS did not propose the Black students get at least

7delegates to the 7 white SDS delegates. The Black students and their

Harlem allies were the main force and had provided such great

leadership for the campaign—and it was not their fault that

because of Columbia's racism there were so few Black students. It did

not make sense that the white SDS students could out-vote the Blacks

let alone the new mass of more moderate white students just joining

the movement after the Police Bust. Fortunately SDS and many other

white students did respect and grasp Black leadership and were united

on the Six Demands of the movement. It is a credit to the white

students and the leadership of SAS and SDS that they did not provoke

a split by trying to overrule the Black students who clearly would

have left the strike committee under those circumstances.

But

now, the SAS/SDS bloc had to worry that their votes and power would

be vitiated by the thousands of new people, almost all white, who

wanted to join the strike. SDS and SAS made what was in fact a very

generous offer. Any additional 70 people who organized themselves

into a working group could get one vote on the strike committee

providing, of course, that they supported the Six Demands of the

Protests since that was why people were now going on strike.

The

Grad-Facs (Graduate Faculty) put forth the most manipulate demagogic

proposal. They thanked SAS and SDS and the Strike committee for

agreeing that every additional 70 people who supported "the

strike" could get one vote but they argued that the new

delegates did not have to agree to support the Six Demands or demand

the end to the Gym or IDA. They even accused the Black students and

SDS of not being "democratic" by "imposing" these

demands on the new white students who had done nothing to support

those demands in the first place. So here was another dilemma for the

organizers. If we told the new members of the Strike Committee they

had no right to mess with the demands but could participate in the

discussions of the strike, the right-wing liberals would have split

the forces and yes, there was danger of isolation. If on the other

hand, we said that Columbia's role as a slumlord, Gym Crow

gentrifier, and human rights violator was "negotiable" then

we could be accused of selling out the demands of the Black community

and the people of Vietnam in an unprincipled pursuit of popular

support of white students at an imperialist university.

Right

or wrong, the SDS leadership agreed that the new 70 member groups had

some power to debate the demands and we took the responsibility to

win those debates. As one example, I was asked by the SDS Columbia

chapter leadership to argue for the strike demands to a mass meeting

of more than 300 new strike supporters in a large auditorium I think

in the Architecture school. I began by challenging the white

students to ask themselves whether they believed they had the "right"

to vote, as privileged beneficiaries of a racist, imperialist

university, as to whether Columbia in turn had the "right"

to be a slumlord in Harlem, had a right to build Gym Crow, had the

"right" to conduct research on mass weapons to kill

civilian populations in violation of the Nuremburg statutes. Many of

the white students were Jews, as was I, and I argued they had to

grasp the present Holocaust being imposed on Black people in the U.S.

and the people of Vietnam—and many of them did. I argued then

as I do now that "Human rights and civil rights are not subject

to ‘majority vote’ by those who are inflicting or

benefitting from those abuses by our government.”

That

was the moral argument. But, in that they did have a "vote"

in the strike committee and since we urgently wanted to win those

demands against Columbia I had to convince them to support The Six

Demands. I argued that they had a moral obligation to vote for human

rights and against racism and genocide. I said they had a moral

obligation to stop Columbia as a slumlord and war criminal and yes,

in the arguments of the times, challenged them to not be "complicit"

in those crimes by even passive support. I challenged them to support

those in SAS and SDS who had occupied the buildings, had stood up to

the police, put their bodies on the line, yes, had risked their

continued student status at the university, and had fought for the

people of Harlem and Vietnam. "You can't make your support

conditional on re-debating the demands of the campaign. You must

support the Six Demands of the Campaign fully and enthusiastically

with gratitude to those who had the courage to lead." And then I

ended with the punch-line, "And think of what a great victory it

would be if we were able to force Columbia University to stop

construction of the gym and end all ties to the IDA--think of how

people in Harlem and Vietnam would appreciate what you did."

Then

we had to confront those on the strike committee who argued against

our demands for amnesty and the dropping of charges. Again the

pro-Columbia liberals were very clever. They argued, "Well, if

you chose to violate the rules and seize property and fight the

police, in the spirit of civil disobedience why aren't you willing to

suffer the consequences?"

We

replied that if the University was evicting people from their

apartments, building a racist gym, and participating in the murder of

civilians, part of our political victory was to force them to accept

the righteousness of our actions and to stop repression against the

movement. If Columbia could bring in the police, get people sent to

prison on political charges, suspend and expel students, then it

would have a chilling effect on future protests – which is

exactly what the university wanted. We argued, "Do not hide

behind civil disobedience which none of us thought we were doing—if

a racist court sends Black people to prison for registering to vote,

who are you to call that justified. And what of the Black students

at Columbia who had to fight to just get into this racist

institution. Now that they fight for their community you white

liberals want to have them face charges, suspension and even

expulsion. Why don't you just go to work for the University and stop

pretending to support the strike? "

And

while we had to win this debate day by day, through this process we

won many hundreds of students to not just support the Six Demands,

but angrily reject the manipulation of the Grad-Facs and later,

Students for a Restructured University.

Keeping

up the protest movement and building the Liberation University

So

now thousands of students were on strike—but now what did we do

with people? Many students agreed to boycott classes but how did we

prevent them from just "dropping out" and going back to

their dorms or apartments and disappearing? We at the Strike

Committee came up with two interrelated ideas—keeping up

demonstrations and actions throughout New York, especially in Harlem

and building a Liberation School on the Columbia campus to show an

alternative university as the revolution right inside the very

institution we were shutting down.

As

I wrote in 1968 in The Movement magazine, "The liberation

classes served several functions:

1.

to give students an example of the type of university Columbia could

be under different political conditions.

2.

To keep students occupied and on campus.

3.

To provide a unique opportunity to put forth radical critiques and

solutions to political questions in courses taught by radicals from

around the city, many of who were not ‘professionals.’

4.

To provide an opportunity for radicals to show that they could run

institutions competently and democratically.

"Many

students were rapidly changing their opinion of the left, and

although still suspicious, were becoming increasingly open to ideas

that only a few weeks before they would not have considered. It

became clear that while some peoples' ideas change through

discussion, action can provide a political context in which those

discussions can be most fruitful. For many, resistance to radical

arguments stems, not from disagreeing with the particular issue being

discussed, but from a belief that radicals can't win. At Columbia,

thousands of students came to believe that the left was, or perhaps

could be, a real force in this country. And because of that

feeling, they became more open to our politics."

I

then went into a detailed discussion of the strengths and weaknesses

of the Liberation School experiment. But in retrospect a lot of that

was metaphysical—"wishing" we could have gone from a

protest group to a disciplined mass organization with infinite

organizational skills and capacity. In reality, the Liberation School

was a smashing success—we built an alternative out of whole

cloth, figuring it out on the fly. The Liberation School involved

more than 1,000 students in classes on the lawn, in classrooms, some

academic, some strategic, some interesting, some boring, but all of

them real and carried out by radical students and their community

supporters. I taught a course on radical movements on the Columbia

lawn—the organizer as radical educator. We had succeeded

beyond any historical expectations.

The

Unfolding Dialectic of Direct Action—Maintaining

the Momentum of the Strike—expanding the scope of protest while

the strike continued

As

I wrote in 1968, "After the first bust the momentum of the

strike could be described as steadily declining, with frequent

exciting incidents temporarily halting that decline. The problem of

maintaining cohesiveness and commitment, always a difficult one, was

greatly influenced by the nature of how the strike began. The fact

that the original defining character of the strike was its tactics

continued to influence its development throughout its duration. As a

result, the leadership of the strike spent a great deal of energy

planning a series of confrontations that would keep the pressure on

the administration and maintain a sharp focus on the strike.

Considering the great difficulty of such a strategy, they were quite

successful.

Expanding

the Action

"There

were many actions: a demonstration against a university ban on

outsiders coming into campus, rallies with people from Harlem, a

demonstration by the moderates on the strike committee to retest the

ban on indoor demonstrations, and most successfully, a joint sit-in

with community residents in Morningside Heights who seized a building

Columbia owned because of high rents, poor services, and efforts to

evict them. Over 140 people were arrested, about half students and

half tenants, and hundreds more were in the street." Fifty years

later, the significance of this is hard to grasp—the Black and

white students increased their commitment to Harlem and expanded

their struggle against the Gym to Columbia as a slumlord, and The

Movement as an ally of Black and Puerto Rican tenants.

"Finally,

on May 21, there was the second bust. The police were called in to

clear demonstrators protesting the disciplining of six students who

participated in an earlier demonstration against I.D.A. Police

stormed through campus, clubbing demonstrators and non-demonstrators,

students who supported the strike and students who couldn't care

less. Even though they were ordered to clear the campus some police

went inside dormitories to beat up students. Students retaliated by

throwing cobbled stones ripped up from the walk, and dropping heavy

objects off the tops of buildings on to police cars. More than 70

Columbia students arrested inside Hamilton Hall were immediately

suspended by the Columbia administration.”

The

victories of May.

If

the SAS and SDS "only" occupied 6 buildings and put

Columbia on the political defensive and won great support in New

York, the U.S. and the world, that would have, of course, been a

profound victory. But those forces continued the tactical offensive

to win their demands throughout all of May under very difficult

conditions. During this period, when the administration played a

consciously passive role, momentum was difficult to keep up because,

without a visible common enemy, the direction of the strike had to

come from within. While the SDS chapter at its core was a small,

perhaps 25 to 50-person group, and SAS had also been transformed to

Black Students of Hamilton Hall, it was miraculous that those forces

who had as late as mid-April worried that their campaign would have

little support were now leading a movement of thousands of students,

and many thousands of Black and Puerto Rican and white

liberal/radical supporters.

SAS/SDS,

who did not have a long history of collaboration, were forced by

history to work far more closely together and work out contradictions

in the process of organizing. It is a great achievement that they

were able to transform the character of the strike from a mass

confrontation, to a sustained mass action, to a coherent campaign

with clear demands and broad mass support, and were also able to

isolate the Columbia University administration despite its powerful

ruling-class allies—or perhaps because of them and the

growing mass, moral revulsion against The Establishment.

The

leadership of the strike, and the hundreds of others who worked hard

on keeping the strike going, were painfully aware of the problems

being encountered, and, yet, kept solving the problems put before

them. This was an historic experiment in Mass Politics. SAS, SDS,

and The Strike Committee were not a bureaucracy making decisions and

implementing them in a vacuum. Both SAS and SDS were a group of

people—most of them from 18 to 22 years old, often very new to

this level of spotlight and leadership, functioning and functioning

effectively in the midst of powerful political currents. When

things were moving, they moved with enormous force and rapidity. When

periods of inertia set in, the malaise was overpowering.

All

great revolutionary victories must have some element of good fortune

and the benefit of our adversaries, far more powerful than us, making

major mistakes of arrogance, miscalculation and brutality, and

carrying out indefensible, immoral policies. Harlem, SAS, SDS, and

their allies defeated the Columbia University ruling class, Mayor

John Lindsay, the New York Times, and the NYPD. In the end Columbia

University agreed to stop the construction of Gym Crow, agreed to end

all institutional relationships with the Institute for Defense

Analyses, and even beyond the immediate demands of the campaign but

clearly as a result of it, in the fall of 1968 called on the U.S.

government to immediately withdraw all U.S. troops from Vietnam.

As

I wrote in 1968, with such great hope and optimism,

"The

Columbia strike, more than any other event in our history, has given

the radical student movement the belief that we can really change

this country. If we are successful, we can use the university as a

training ground for the development of organizers who will begin to

build that adult movement we talked so much about."

In

Praise of radical and revolutionary organizations who challenge

the U.S. Empire

On

the 50th anniversary of The Struggle Against Columbia it seems like,

"A long time ago in a galaxy far far away." I am so lucky

to have lived through the Great Revolution of The Two Decades of the

Sixties because I truly saw a revolution with my own eyes—a

revolution that shapes my organizing work today.

During

The Sixties I was given the gift of working with the great

organizations and leaders of our times. Millions of our lives were

shaped by the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, Mississippi

Freedom Democratic Party, Congress of Racial Equality, Southern

Christian Leadership Conference, Students for a Democratic Society,

Young Lords Party, American Indian Movement, and the Black Panther

Party.

Our

lives and life choices were a product of Third World Revolutions that

created the historical events, international conditions, and mass

consciousness of the times. Whether people understand it or not, the

events of 1968 were on a direct continuum with the Haitian revolution

of 1794, the Great Slave Revolts that swung the civil war to the

North in the 1860s, the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Chinese

revolution of 1949, the Cuban revolution of 1959, and the great

African revolutions of the Congo and Ghana in 1960 and beyond. The

Sixties were profoundly determined by the Great Vietnamese Revolution

against French and U.S. Genocide— beginning with opposition to

the French invasion of Vietnam in the 1850s, through World War I and

World War II, culminating in the defeat of the French at Dien Bien

Phu in 1955 and the U.S. in 1975.

It

was also a period shaped by such great revolutionary intellectuals,

organizers, and mass leaders who carried out the most revolutionary

rejection of White Settler State U.S. colonialism and imperialism,

and who built an entire worldview of counter-hegemonic thought and

ideology to delegitimize the system and legitimize The Movement—Black

and Third World revolutionary thought.

The

image of Black students at Columbia being schooled by the great Black

thinkers of the time—James Bevel of SCLC, H. Rap Brown and

Stokley Carmichael of SNCC, John Henrik Clark, and James Baldwin is

inspiring to me to this day. And their generation was the product of

the work of W.E.B. DuBois, Paul Robeson, Claudia Jones, William L.

Patterson and the great Black communists who wrote We Charge

Genocide--the Crime of the U.S. Government Against the Negro People

and presented it to the United Nations in 1951.

By

the 1960s, our generation's radicalism took the form of courageous

action, making moral choices, confronting individual and group

sacrifice, and a speaking out with force and conviction against the

profound moral depravity of our own government.

At

the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Justice, Dr. King called

out the United States for duplicity against the Negro people.

In

a sense, we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a

check. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given

the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked

‘insufficient funds.’"

At

Berkeley in 1964, Mario Savio gave voice to many students at U.S.

universities

There's

a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you

so sick at heart, that you can't take part! You can't even passively

take part! And you've got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon

the wheels…upon the levers, upon all the apparatus and you've

got to make it stop! And you've got to indicate to the people who run

it, to the people who own it, that unless you're free, the machine

will be prevented from working at all!

By

1966, Muhammad Ali, a great political thinker, gave voice to Black

people's opposition to the war in Vietnam,

Why

should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from

home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while

so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied

simple human rights?

No,

I am not going ten thousand miles from home to help murder and burn

another poor nation simply to continue the domination of white slave

masters of the darker people the world over. This is the day when

such evils must come to an end. I have been warned that to take such

a stand would put my prestige in jeopardy and could cause me to lose

millions of dollars which should accrue to me as the champion.

But

I have said it once and I will say it again. The real enemy of my

people is right here. I will not disgrace my religion, my people or

myself by becoming a tool to enslave those who are fighting for their

own justice, freedom and equality…

If

I thought the war was going to bring freedom and equality to 22

million of my people they wouldn’t have to draft me, I’d

join tomorrow. But I either have to obey the laws of the land or the

laws of Allah. I have nothing to lose by standing up for my beliefs.

So I’ll go to jail. We’ve been in jail for four hundred

years.

In

the Struggle against Columbia, we felt a profound moral obligation to

defend Black people in the U.S., the people of Vietnam and the people

of the world from the assaults of our government. We agreed with Dr.

King that the United States was "the greatest purveyor of

violence in the world." We saw our role, as it is today, to

challenge every institution of which we were a part, to develop the

most radical and structural demands against the system, and to

develop forms of organization and forms of struggle, that is,

tactics, to carry out those objectives. We all wanted to be part of

organizations and looked to national organizations with local,

city-wide, and regional chapters as the best form of challenging the

system.

In

the Struggle Against Columbia, SAS and SDS built the broadest

possible united front in support of the Six Demands. We were generous

and inclusive but not stupid—we understood our moral

responsibilities and would not sell out the cause to which we had

dedicated ourselves. We confronted and isolated the cynical corporate

liberals among Columbia students and faculty who were little more

than proxies for the Columbia administration. The vast majority of

students, Black and white, saw Columbia the slumlord, Columbia the

gentrifier, and Columbia the war criminal as a clear morality play in

Black and white and saw the Six Demands as a clear Black and white

answer. We fought with both innocence and sophistication to defeat

powerful ruling class forces.

Today,

we are living in a Great Counterrevolution Against the Great

Revolution of the Two Decades of the Sixties. The greatest weapon of

the counter-revolution is to caricature and slander the great radical

and revolutionary organizations that made history. Many of us, as

veterans of those movements, can tell you better than our enemies the

many mistakes, errors, even abuses we carried out in the process of

fighting for a better world. Within months of the great Columbia

victory, the Progressive Labor party inside SDS came up with a new

line, "All nationalism is reactionary" and began attacking

Black studies, Black liberation, Black Panthers and even the

Vietnamese Communist Party for exercising self-determination in its

negotiations with the U.S. to end the war. Another faction of SDS,

calling itself the "Revolutionary Youth Movement" was

adamant in its support for the Black movement and the people of

Vietnam. But in its tactics of believing it was leading the struggle

against P.L. in fact turned on virtually everyone but themselves and

ended up played a destructive role by rejecting the mass, radical,

character of SDS agreeing with PL that SDS would be a playground for

factions and little else.

Throughout

that I stood close to my principles and the politics of the broad

united front I had learned in my work in the Civil Rights and Black

Liberation movement and what I thought were the "lessons from

Columbia" that still guide my work today. I went back to Boston

University where along with Craig Kaplan, Don Alper, Nora Tuohey,

Sherrie Rabinowitz and other SDS members, and in close alliance with

great faculty Howard Zinn and Murray Levin, we built BU SDS into a

powerful mass radical organization.

We

initiated our Anti-military campaign that called in Boston University

to prohibit Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) from being on the

campus and to end its B.U. Overseas Program in which BU faculty

taught at U.S. military bases all over the world. We fought on the

side of Chuck Turner and other Boston/Roxbury Black organizers to

challenge white trade unions and white construction workers to demand

Tufts University hire Blacks in its construction projects, fought for

Black Studies, and worked closely with the Boston Black Panthers. We

did not attack other SDS members or each other and somehow managed to

survive both PL’s growing chauvinist impact on other SDS

chapters.

But

SDS did not survive. By the SDS Convention of June 1969, only a year

after the great Columbia victory, SDS had destroyed itself and could

not blame the U.S. government for its descent into sectarianism and

white chauvinist self-importance. Even at the Convention, I and

others tried to find a "3rd road" but while I was a very

effective organizer I was not up for the job of leading a left

tendency in bitter factional battle. At that time, the idea of SDS as

a radical, non-sectarian, mass anti-racist, anti-imperialist

organization with deep devotion to real Black people and the real

people of Vietnam was an idea whose time had gone.

SDS

had a great run. The job of building and sustaining a national

organization is very difficult and most organizations eventually fall

of their own weight and their inability to solve their own internal

contradictions. For those who continue to be outraged about the

crimes and punishments of The System, the idea is to learn the

lessons, look in the mirror, and move on to another form of

organization that you believe is more relevant and righteous and get

on with the work. That is what I have done my whole life and will

continue as long as I live. For me, my fight continues with the

racism, imperialism, and ecological catastrophe of my own government

aka U.S. imperialism so I am always in search of an organization in

which to do my work.

Those

of us today who continue the search for national and international

organizations to challenge the U.S. Empire can give no assurances

that similar problems will not occur again— for they are in the

human condition. Certainly any effort to bring together 5, 10, 100,

let alone 1,000 or 10,000 or more people in one organization will

confront old and new challenges.

But

what cannot be denied is that we of The Sixties carried out the

Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Freedom Rides, the March on

Washington, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and Occupation

of the Pentagon. We passed the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights

Act, elected Black mayors, fought at Wounded Knee, led anti-war

protests among G.I.'s and for a moment, slowed down racist violence

and ended the war in Vietnam.

It

is not our fault that The System fought back with a vengeance, killed

the Black Panthers, used COINTELPRO to infiltrate our organizations,

and carried out the greatest re-enslavement of Black people as 1

million Black people are in prison and millions more face police

brutality and occupation every day of their lives. It is The

System’s Fault that the Democrats under Clinton ended welfare

and passed the "anti-terrorist and effective death penalty act."

It is the System’s Fault that Barack Obama with 8 years in

office stood by as the Republicans destroyed the Civil Rights Act and

the Voting Rights Act as he and the Democrats made weak noises of

protest and did nothing to fight for those rights.

It

was unimaginable in 1968 that U.S. and world imperialism would

pollute the planet with such a vengeance and emit so many greenhouse

gases that the future of the world, beginning with the very survival

of Africa, hangs in the balance.

In

the midst of this U.S. Holocaust against the world, it is beyond

disgraceful to hear people today, repeating the "lies the system

taught me," say with so little investigation, or empathy let

alone admiration— "SNCC did this wrong, SDS did that

wrong, Black Students at Hamilton Hall did that, Dr. King and Malcolm

did not understand this and that, and the Panthers did that."

Without radical and revolutionary organizations there is no hope for

radical and revolutionary change and Columbia was one of the high

points of successful, creative, organization and organizing.

Especially because The Struggle Against Columbia was such a great

victory for The Movement we need to study and restudy and debate its

lessons as one of the most successful Black/white collaborations and

a great synthesis of militant, radical, and revolutionary mass and

popular politics.

The

central problem facing the movement today is an epidemic of

anti-communist, anti-left, anti-Black nationalist, anti-Third World,

and anti-organizational individualism. The central challenge, that so

many of have tried to solve with little success for decades, remains—

How can we rebuild a national and international movement against the

U.S. government and imperialism and how can we build a movement, led

by Third world people inside and outside the U.S., that anti-racist,

anti-imperialist, environmental justice, independent and to the left

of the Democratic Party.

At

Columbia under enormous odds, the Black Liberation Groups of Harlem,

SAS, SDS, and all of us thought we were part of a world movement in

which we told the system "the whole world is watching." I

am so proud to have been part of that movement where I showed up, did

my job, and, as an ally of SAS and an organizer for SDS, helped to

stop Gym Crow and force Columbia out of the IDA.

Today,

I work with Black and Latino organizers who in turn are working with

hundreds of Black and Latina high school students along with veterans

of the civil and human rights movement in South L.A., city-wide and

nationally. We are calling for an end to U.S. Genocide against the

Black Nation, Free Public Transportation, No Police on MTA Buses and

Trains, No Police in the Schools, Stop MTA Attacks on Black

Passengers, and an end to U.S. drone attacks all over the world.

I

am spending even more time reading and writing revolutionary history

so that I can help today's movement grasp the great achievements of

our past to once again fight for a hopeful and revolutionary future.

Join the Strategy Center in New York April 23

Click here for more info

|