|

Rikers

Island is closing. Although it will not happen overnight and will

likely take years to accomplish, the behemoth complex of jails known

for its brutality, torture and other human rights abuses will be shut

down. Over the years, Rikers has earned the reputation as America’s

most notorious prison.

In

a March 31 press conference with New York City Council Speaker

Melissa Mark-Viverito, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced the 10-year

plan to close Rikers.

“New

York City has always been better than Rikers Island. I am proud to

chart a course for our city that lives up to this reality,” de

Blasio said. “Our success in reducing crime and reforming our

criminal justice system has paved a path off Rikers Island and toward

community-based facilities capable of meeting our criminal justice

goals.”

Noting

that Rikers Island is part of a national problem, the mayor said

that, while the mass-incarceration problem did not begin in New York,

it will end there. Since the facility opened in 1932, this marks the

first time the city has made closing Rikers its official policy.

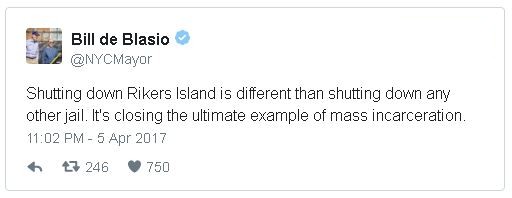

Mayor

de Blasio tweeted about the significance of this decision:

Shutting

down Rikers Island is different than shutting down any other jail.

It's closing the ultimate example of mass incarceration.

Although

the jail has been around for 85 years, Rikers Island has an older

history fittingly steeped in the enslavement of Black people. As Vice

reported, the Rikers (the Anglicized version of Rycken) were a

wealthy Dutch family that settled the island in the 1660s at a time

when New York was still known as New Amsterdam. From 1815 to 1838,

the family patriarch, Richard Riker, oversaw the city’s

criminal court. Part of his responsibilities included deeming free

Black children, women and men as “fugitive slaves,”

allowing for their kidnapping to the South by bounty hunters without

a trial. Riker received kickbacks from slave catchers, and he and two

slave-catching police officers were known as the “Kidnapping

Club” by abolitionists.

Sadly,

this sordid history of Rikers Island has continued to plague the

facility, which is the second-largest in America after Los Angeles

County Jail. The conglomeration of 10 jails sitting on the 400-acre

island houses mostly men (93 percent), but also women and juveniles.

Throughout a given year, 77,000 people go through Rikers, with 10,000

inmates detained on a given day. In the 1980s and 1990s, the jail

population was double current numbers. The prison population is 89

percent Black and Latino (56 percent African-American and 33 percent

Latino) — from New York’s low-income communities —

and only 7.5 percent white.

Eighty-five

percent of Rikers inmates have not been convicted of a crime and are

pretrial detainees, with the rest serving short sentences of a year

or less, as

The

New York Times

reports.

Around 40 percent of detainees have a mental illness, according to

the Urban Institute.

The

decision to close Rikers comes in the midst of longstanding problems

of violence, brutality and inhumane living conditions for those

detained there. For example,

mentally

ill detainees

have

died in custody. Rikers continues to place inmates in

solitary

confinement,

an internationally condemned form of physical and psychological

torture, with Black and Latino inmates subjected to the punishment at

a much higher rate than whites.

According

to a report from the federal monitor overseeing Rikers since 2015,

the abuse continues, with guards using excessive force at an

“alarming rate.” For example, it is common for correction

officers to place inmates in chokeholds, punch them in the head while

handcuffed, slam them into walls and douse them with pepper spray.

The jails also are an environmental disaster, with regular flooding,

crumbling infrastructure with dilapidated facilities, a putrid

landfill and pollution-belching power plant, and overheated

conditions that have given Rikers the nickname

“The

Oven,”

as

Grist reported. With no central air conditioning in the summer

months, some prisoners have suffered from cardiovascular conditions,

heat stroke, rashes and asthma, and some have attempted suicide. One

homeless veteran was

baked

to death

in

his hot cell that overheated to at least 100 degrees from faulty

equipment.

Things

came to a head with the story of

Kalief

Browder,

who was arrested and sent to Rikers at age 16 for allegedly stealing

a backpack. He was never charged. While there, in a story revealed by

The New Yorker,

Browder

endured three years of torture

at

Rikers, including beatings by guards from his first day behind bars,

and starvation. After his release, Browder committed suicide in June

2015 at age 22, using an air conditioning cord to hang himself. This

was a consequence of depression from the abuse he had suffered. The

Marshall Project interviewed his mother, Venida Browder, for a video

series called We Are Witnesses.

New

York City Public Advocate Letitia James wants to rename the island

after Browder, given the planned shuttering of the infamous jail.

Although

de Blasio has invested hundreds of millions of dollars to improving

conditions at Rikers, the time has come to phase out America’s

most notorious jail. A

report

unveiled

by the Independent Commission on NYC Criminal Justice and

Incarceration Reform maps out a plan to shut down the jail.

Condemning the facility as a “19th-century

solution to a 21st-century

problem,” the commission calls for reducing the jail population

by half to 5,000 and placing the remaining inmates in new facilities

around the city.

The

report makes a number of other recommendations, including reforming

arrests by diverting tens of thousands of low-level offenders from

traditional prosecution and reducing the number of people in pretrial

detention so that people do not have to wait months or years in jail

for the resolution of their cases.

“Finally,

we recommend an approach to punishment that prioritizes meaningful

sentences and a judicious use of incarceration for all types of

cases,” the report said.

Rikers

Island has been used as a torture chamber for Black people for far

too long. Its end will come, though not soon enough.

This commentary was originally published by AtlantaBlackStar

|