|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

This article originally appeared in In Motion Magazine. Every year, millions of Americans pay tribute to the memory of

Dr. Martin Luther King. We often forget, however, that King was

the object of derision when he was alive. At key moments in his

quest for civil rights and world peace, the corporate media treated

King with hostility. Dr. King's march for open housing in Chicago,

when the civil rights movement entered the North, caused a negative,

you've-gone-too-far reaction in the Northern press. And Dr. King's

stand on peace and international law, especially his support for

the self-determination of third world peoples, caused an outcry

and backlash in the predominantly white press.

The Washington Post denounced King's anti-war position,

and said King was "irresponsible." In an editorial entitled "Dr.

King's error," The New York Times chastised King for going

beyond the allotted domain of black leaders -- civil rights. TIME called

King's anti-war stand "demogogic slander...a script for Radio Hanoi." The

media responses to Dr. King's calls for peace were so venomous that King's

two recent biographers – Stephen Oates and David Garrow – devoted whole

chapters to the media blitz against King's internationalism.

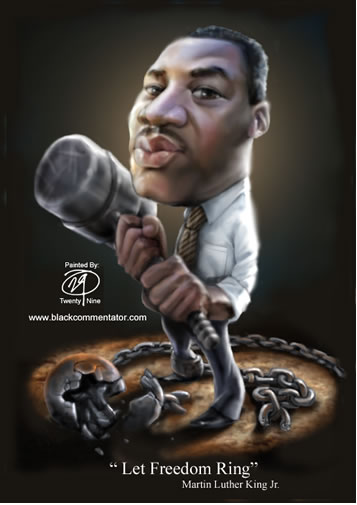

View printer friendly version of the digital painting of Dr. King In 1986, Jesse Jackson wrote an essay on how Americans

can protect the legacy of Dr. King. Jackson's essay on

the trivialization,

distortion, the emasculation

of King's memory, is one of the clearest, most relevant appreciations in print

of Dr. King's work. Jackson wrote: "We must resist the media's weak and

anemic memory of a great man. To think of Dr. King only Paul Rockwell, formerly assistant professor of philsophy at Midwestern University, is a writer who lives in Oakland, California. |

| January 13 2005 Issue 121 |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Printer Friendly Version | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| |

|||||||||

| |

|||||||||